Stakeholders and Design

The formation of the CMIS involved adaptive iteration with multiple stakeholders. The CMIS started eight years ago as a basic computer system compiled by an IT staff member in the Ministry of Justice and Public Security (MJPS). USAID improved on the system with templates that similar systems in other countries had used. PROJUSTICE, a previous USAID governance- and justice-related project in Haiti, recommended this approach and began the formal implementation of CMIS in 2015.

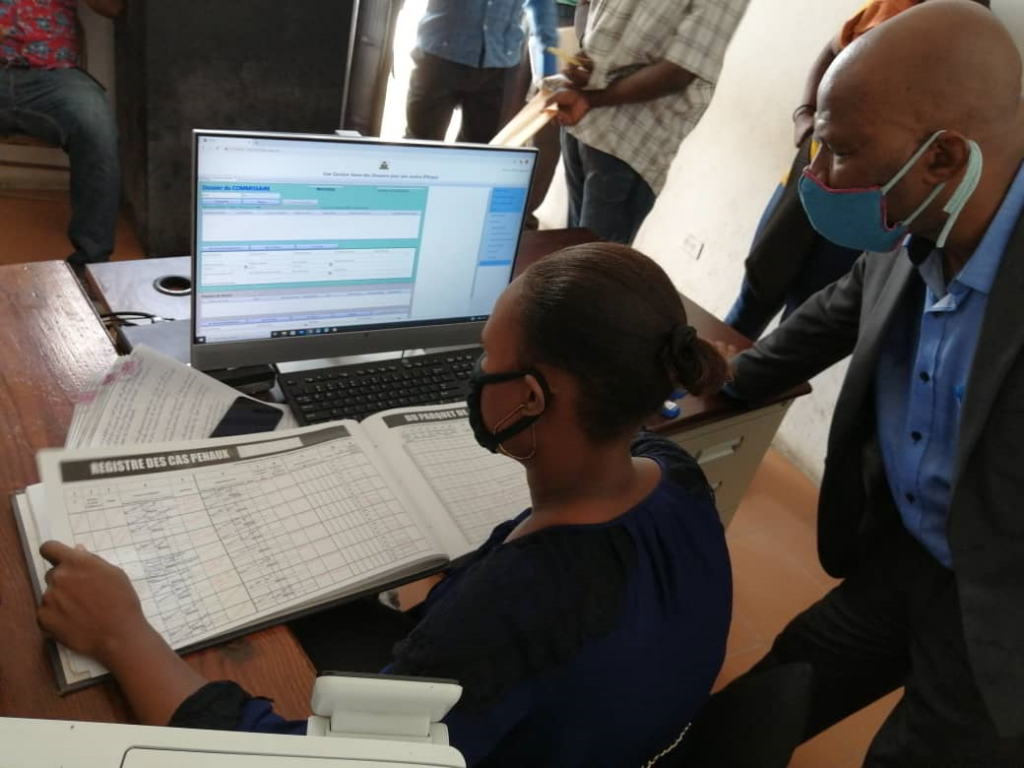

The CMIS was designed to facilitate case management by making it possible to monitor the progress of prosecutors and judges in clearing dockets. To ensure the system responded to the needs of prosecutors and judges, USAID and JSSP involved them in designing the CMIS, adjusting it based on their feedback.

The feedback from independent entities within the justice system allows the CMIS to provide more accurate assessments of caseload completions and case processing times. These assessments, in turn, facilitate situations such as judges’ performance reviews. With this data, a review committee can promote more capable judges, helping to ensure the judicial system’s strength.

These institutions can also independently oversee critical parts of the CMIS’s maintenance and expansion. Other key stakeholders developed best practices in using the CMIS, practices that USAID and JSSP showcased in stakeholder meetings and social media to foster local ownership of the system.

The CMIS is a powerful asset for MJPS, which represents prosecutors, and for CSPJ, which represents judges. Both entities ensure the independence of the judiciary.

“The case management information system, which is operational in 11 jurisdictions, is a revolution in the sector,” said chief judge and CSPJ board member Noe Pierre Louis Massillon. “It allows us to combat prolonged pretrial detention by providing data … It’s such a success that the CSPJ will introduce a budget line item to ensure that the system keeps being operational at the end of the JSSP program.”

Passing the Dashboard Baton to the Haitian People

Although JSSP is scheduled to end in 2022, the project has laid the groundwork to transfer the CMIS to MJPS and CSPJ. A transition plan is underway with two groups involved: the Technical Coordination Unit of CMIS (UCOTES), a joint technical committee comprising IT specialists from MJPS and CSPJ who are tasked with all technical issues, and a national committee comprising high-profile representatives from these institutions who are tasked with making key decisions. UCOTES installed cabling in the last six courts that implemented the CMIS. The financial units from MJPS and CSPJ are preparing budgets to ensure they will completely oversee the system’s expansion costs in other courts. As a result, CMIS will continue beyond JSSP.

Hopefully, the era of hunting for case files, dealing with corrupt clerks, and guessing caseloads has ended. Judges and prosecutors who’ve experienced the CMIS appear to have no interest in returning to that time. As Magzeda Paul Andre, a prosecutor in Grande-Riviere-du Nord, expressed, “I have been wishing all my career of such a revolution in the justice sector in Haiti. It is finally a dream come true.”