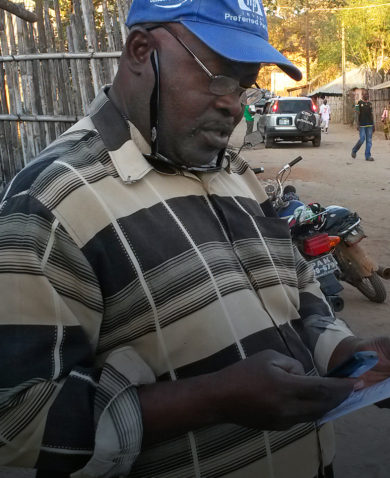

The findings were useful to adapt program planning. The Mozambique project worked with two types of populations, one living on the oceanic coast and the other living on internal coasts by rivers. Part of the project was to increase the populations’ awareness of the climate issues they face, along with increasing awareness of potential mitigating solutions; the CCM’s revelation that there was a shared understanding among both populations (hundreds of miles apart) meant that the project did not need to develop distinct messages for different populations, saving funds.

In Haiti, the project identified many reasons that people avoided lawyers and courts. The CCM revealed that many citizens preferred informal justice mechanisms to formal ones for resolving conflicts, including serious crime. The project developed targeted interventions to strengthen both formal and informal mechanisms after the CCM identified the types of disputes people took to various institutions. The findings helped stakeholders identify some ways that formal justice mechanisms could leverage the advantages people recognized in informal mechanisms, such as connecting formal justice actors more directly to the communities they serve.

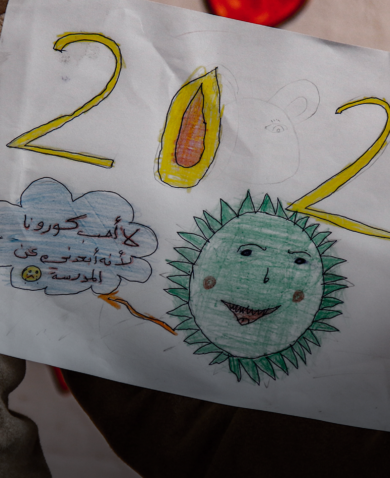

In the West Bank, an NGO conducted awareness campaigns to judges and to women about women’s inheritance rights under the law, but after the CCM surfaced a potential unintended consequence of male violence against women who claimed their rights, the NGO adapted its outreach efforts to men as a key population subgroup to promote their understanding and acceptance of women’s inheritance rights.

The GIC’s first article submitted to a peer-reviewed academic journal was published in November 2019, in the Journal of Social Science & Medicine – Population Health’s special edition on gender equality, empowerment, and health. This article (available for free as an open-access article) provides greater detail on the methodology and its application in Palestine.

Innovative, cross-sector collaboration can accelerate the results of development projects, as does the collaboration between institutes of higher education and practitioners. The GIC has been a successful experiment in collaboration, pairing experienced academic researchers with an experienced development organization. Our use of the CCM in global development demonstrates how this low-resource approach can identify cultural complexities that can make or break the success of an activity — and keep your strategy from becoming breakfast!

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.