Rapid Research and Behavior Change in Conflict-Affected Syrian Schools: An Oxymoron?

October 8, 2021 | 5 Minute ReadHow Syrian educationalists used rapid research to nudge teachers’ engrained discipline habits and behaviors.

Tragically, corporal punishment, humiliation, and other negative discipline techniques are common practices in Syrian schools. Conflict traumatizes teachers and robs them of training opportunities, often giving rise to a culture of physical and mental punishment.

The Chemonics-led Syria Education Programme, which has provided nearly half a million primary-school-age children with a safe and quality education, trains and supports teachers to deploy positive, child-friendly behavior management techniques.

The team’s approach focuses on cultivating the use and culture of positive discipline to move teachers away from using negative discipline techniques. A negative discipline approach relies solely on punishing what is perceived as undesired behaviors. A positive discipline approach incentivizes desired behaviors and creates spaces for discussion, movement, and engagement to support learning. Verbally shaming children in front of their peers for talking in class is an example of negative discipline. Conversely, recognizing children who have engaged in schoolwork and collaborated with their peers as the ‘star of the week’, is an example of positive discipline.

In early 2021, we began to research the best methods for introducing positive discipline to Syrian classrooms. Changing behavior is complicated. Behavior change research frequently ends up sitting unused on the shelf. We wanted to change that. In partnership with Hurras Network, we acted on findings gleaned from rapid behavior change research.

Is Rapid Behavior Change Possible?

Rapid research can be used to understand how dynamics change over a short period of time. In contrast, behavior change typically requires time and deep insight into the populations whose behavior you are trying to change. It is logical to think that rapid research is not suited to evaluating behavior change.

Undeterred, we designed a rapid research project that attempted to assess change in behavior in just six weeks. The project sought to encourage teachers to use positive discipline and shift the practice of negative discipline.

We ran two research cycles across nine schools, commencing with workshops that introduced teachers to positive discipline approaches. The teachers had just under two weeks to implement and test the techniques with peer support from their colleagues. We then gathered data to assess their use of the techniques and adapt our approach.

Capturing Behavior Change

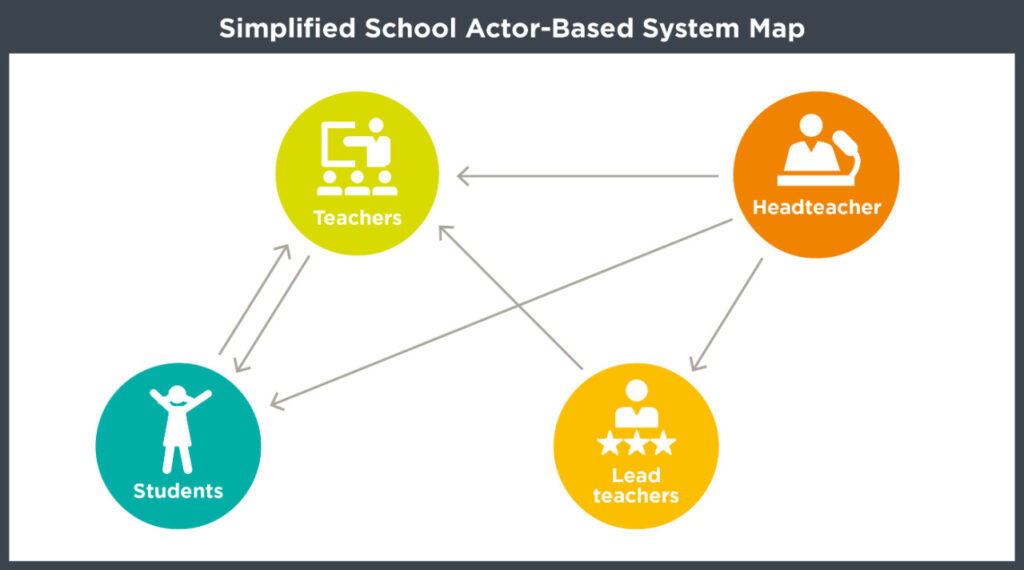

To enable our rapid research to both plan how to change behavior as well as support us in actually measuring and capturing that change, we drew on Actor-Based Change Frameworks (ABC). ABC supports intervention teams to develop a behavioral system map that represents how different stakeholder groups influence one another’s behavior. We would then design the intervention and measurement systems to respond to that system map. This approach would measure the extent — and how well — teachers used positive discipline approaches, while remaining sensitive to how other school actors affect teachers’ uptake of discipline approaches. After all, teachers do not behave in isolation; their behaviors are enabled, inhibited, or influenced by the behavior of their students and colleagues.

We wanted to see whether headteachers adopting a new behavior — like using assemblies to describe and celebrate desired student behaviors or putting up posters to encourage the use of positive discipline — could affect the actions of other actors. The system map revealed how teachers, lead teachers, headteachers, and students influence one another.

This process proved immediately valuable. We realized that teachers were simultaneously the most influenced and the least influential.

Teachers’ lack of influence also meant that, irrespective of their personal commitment, any change in their behavior risked being short-lived. Positive new behaviors may have retreated if met with resistance from more influential actors, such as school leadership, or not supported by broader systemic change. To introduce positive discipline techniques successfully, we had to ensure that teachers’ influencers backed and actively supported change.

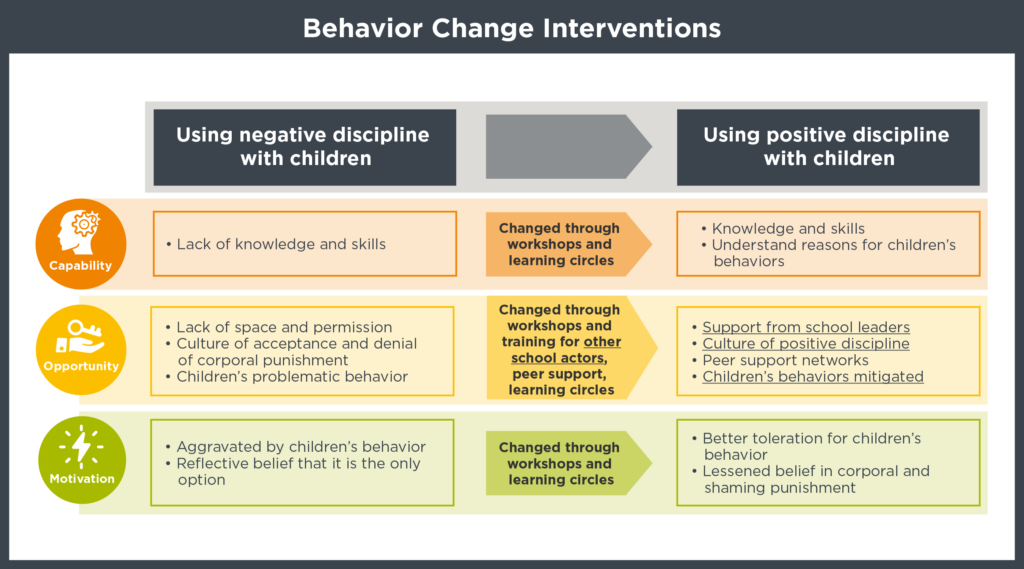

Now able to view the dynamics through a behavioral lens, we used Susan Michie’s COM-B model of behavior to develop a theory of change. COM-B posits that “Behavior”(B) emerges from an actor’s “Capabilities, Opportunities, and Motivations” (COM). Teachers’ capabilities, opportunities, and motivations were largely shaped by other school-system actors. Therefore, to create sustainable change in behavior, we needed to change the actions of students, lead teachers, and head teachers in tandem. Hurras Network calls this a ‘whole-of-school’ approach. The graphic below demonstrates teachers’ capabilities, opportunities, and motivations to use positive discipline and highlights the role of other actors in shaping teachers’ capability and opportunity to use positive discipline techniques. These understanding enabled us to identify audience-specific interventions to spur the systemic change necessary to shift ingrained teaching practices.

Using Evidence to Adapt to the System

We gained valuable insights by collecting data in-line with the theory that emerged from our COM-B framework. For example, after the first research cycle, we saw that uptake was spotty. We learned that teachers felt they didn’t have the time (opportunity) or skill (capability) to execute some of the more complicated positive discipline techniques. The data also revealed that teachers believed (motivation) some positive discipline techniques did not garner the response in their students that they expected. These concerns impeded uptake of some of the new, more progressive discipline methods.

The Hurras Network’s intimate knowledge of the schools meant they developed a solution quickly. In-line with the COM-B theory, Hurras altered how new positive discipline techniques (capability) were introduced to teachers and supported lead teachers to integrate training into supervisees’ career development plans (opportunity). Our goal was to understand and leverage the system to change teaching practices. In just six weeks, the systemic approach worked. When equipped with the right skills and supported by their colleagues and leaders, teachers adopted a wider range of positive discipline techniques.

As teachers’ uptake of positive discipline increased, student behavior began to improve. This, in turn, demonstrated to teachers that the approach was effective, spurring greater adoption of positive techniques and initiating a positive feedback loop. Behavior change became organic.

Beyond simply using new teaching practices, the research showed that even the way that teachers viewed problematic student behavior shifted. To begin with, teachers regarded talking and moving without permission as ‘problematic’ behaviors. By the end of the research, most teachers instead identified aggressive behaviors, such as shoving other children, as an example of problematic behavior. Crucially, teachers’ belief in the efficacy of corporal punishment as a behavior management approach demonstrably decreased.

Reflecting on the ‘Whole-of-School’ Approach

Over the project, we proved that rapid behavior change research is not an oxymoron. A systems-based, or ‘whole-of-school’, approach was critical to making this possible. By understanding how the system worked, we were able to define how and why change occurs. The behavioral system map underpinned our theory of that change, informing how we designed the intervention and even how we collected and made sense of our data. Ultimately, it allowed us to nurture a change that benefited the whole school, not just one actor.

Banner Image: A Syrian girl holds a drawing up for the camera.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.