Unlocking Resilience: The Journey of a Trauma-Informed Education in Northwest Syria

August 22, 2023 | 4 Minute ReadChemonics UK drew from its experiences with fragile and conflict-affected communities worldwide to support potentially trauma-affected individuals in Northwest Syria through its Syria Education Programme.

Psychological, emotional, cognitive, spiritual, and social wellbeing are deeply affected when communities and individuals are exposed to traumatic or distressing events. These feelings can be exacerbated when survivors are excluded from the decision-making processes that shape the response to issues that affect them, making them feel invisible and powerless.

Chemonics UK drew from its experiences with fragile and conflict-affected communities worldwide to support potentially trauma-affected individuals in Northwest Syria through the UK Aid-funded Syria Education Programme (SEP), also known as Manahel. SEP’s approach focuses on healing and promoting individual agency by empowering participants. A strong and inclusive primary education system helps empower individuals, including those of an early age, enabling them to navigate challenges and contribute positively to their communities.

This blog and a new briefing paper capture key learnings from SEP’s work with children, parents, caregivers, teachers, and the community to support the recovery of individuals from potential trauma exposure and distress caused by over 12 years of crises. The insights are organised around three phases of the programme cycle: design, implementation, and evaluation.

Design

SEP’s primary education programme incorporates flexible, psychosocial support activities to enhance the emotional intelligence and resilience which children need to overcome trauma. It offers various activities, from specialised psychological support to engaging storytelling and reading exercises, all aimed at improving children’s mental health and wellbeing.

To involve parents and children in designing the psychosocial support curriculum, the programme initiates workshops at each school. Parents and children come together to review storybooks that teach emotional resilience topics like honesty, kindness, and friendship. Their valuable insights are integrated into weekly guided psychosocial support and reading sessions.

This participatory approach benefits both parents and children, creating a curriculum tailored to their emotional needs and realities, and fostering a sense of ownership and accountability. Caregivers’ increased involvement supports children in overcoming challenges and coping with trauma and distress effectively. Moreover, this approach empowers individuals who have experienced repression, reframing them as key players in their own recovery.

Surveys are sent to parents and school safety officers every three months. Insights from the surveys inform decision-making on which issues to prioritise at each school’s monthly awareness session. SEP also intentionally seeks feedback from children with disabilities, who have historically been stigmatised, as well as marginalised groups to ensure its interventions are equitable and accessible.

Implementation

During the implementation of its primary education programme, SEP takes significant steps to combat mental health stigma and support people with disabilities. For example, SEP established parent-to-parent support groups to create safe spaces for parents and caregivers of children with disabilities, allowing them to share their experiences, challenges, and concerns openly. These groups can address the root causes of stigma, breaking down barriers of isolation and fear, and enabling parents, caregivers and children with disabilities to participate meaningfully in their communities.

The programme also brings together parents and caregivers of children with severe emotional distress, offering a non-judgmental space to share challenges and learn from one another. School protection workers use these sessions to educate parents about their child’s condition and connect them to tailored services.

Through activities such as these, SEP’s approach has fostered community involvement in the social and emotional growth of children, while allowing parents and caregivers to discuss their own mental health vulnerabilities. These conversations are distinct from those with specialised mental health professionals, providing a collective understanding of trauma and a supportive community to promote mental wellbeing.

Evaluation

Data collection in the Syrian context is challenging due to the constantly changing political situation, ongoing violence, and the recent earthquake that hit northern Syria and Turkey. Therefore, trauma-informed programming must be highly inclusive and consider the diverse experiences of the various identities, groups, and communities in Northwest Syria. SEP’s adaptive implementation integrates complexity-aware monitoring principles, continuously seeking feedback from children, parents, caregivers, and teachers to improve the quality and effectiveness of its activities.

To increase a sense of accountability, and to measure the impact of its interventions and inform programme adjustments, SEP conducts quarterly assessments using the Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire (SDQ) with students, parents, caregivers, teachers, and Internally Displaced Persons. The results identify strengths and difficulties impacting children according to their age group, gender, and disability, and help establish appropriate interventions in response to the child’s specific needs. For example, findings from previous quarters identified 21 areas to be improved, including fear, bullying, and social relationships. This led to guidelines and recommendations for school staff, parents, and caregivers dealing with these cases.

The SDQ results also showed a 50% decline in children facing significant emotional and behavioural challenges. These results indicate the positive impact of SEP’s evidence-informed interventions on the mental health and well-being of children.

The involvement of wider communities in the evaluation process helps to situate trauma sensitivity in the larger community context, providing a more holistic understanding of children’s and their communities’ social and emotional needs.

Conclusion

SEP’s trauma-informed approach supports community empowerment and healing from potential distress and large-scale trauma. The programme implements this trauma-informed approach delivery by prioritising individuals’ ownership – through engaging communities, fostering empowerment through network building, and promoting safe and responsive adaptation. By involving children, parents, caregivers, teachers, and communities in the project’s design and implementation, the programme fosters resilience and personal transformation.

Opportunities for Trauma-Informed Action

The following steps are informed by SEP’s approach and designed to support the engagement of children, parents, caregivers, and communities to promote the healing of those affected by distress or trauma:

- Strengthen community support groups by providing a safe environment, and addressing barriers including stigma, cultural differences, or lack of awareness.

- Develop enhanced feedback loops for trauma-affected populations, ensuring their voices are heard and their feedback is considered through frequent and targeted data collection.

- Involve children, parents, caregivers, and communities in designing culturally sensitive and relevant psychosocial support programmes for recovery and healing.

- Develop adaptive programming that evolves with the changing needs of communities affected by distress or trauma, ensuring programming is rooted in highly flexible community-led learning.

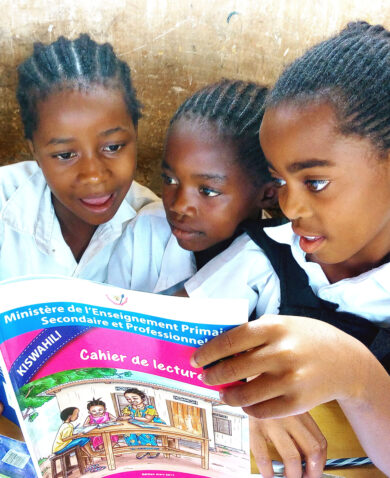

Banner image caption: A pupil participates in a reading session at the school library room in a SEP-supported school in Northwest Syria.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.