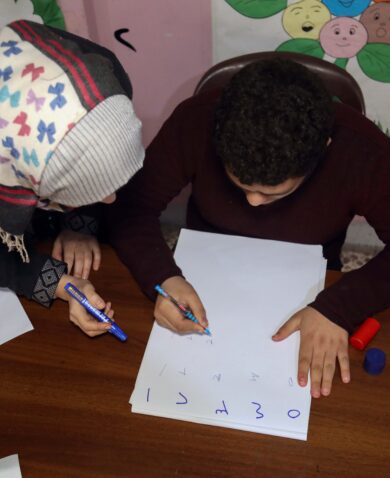

For example, the USAID Tajikistan Read With Me project equipped teachers with decision-making tools to help them take action when they encounter a general or specific challenge in the classroom. When a teacher notices a student having a particular challenge, she can consult her “If/Then/Do” chart and determine an appropriate intervention to give that student more time, more practice, or more ways to close a learning gap or meet a physical or psychosocial need. Teachers experienced more confidence in making decisions to address student needs and felt more equipped to take on challenges. Teachers felt encouraged to try interventions because the decision-making tool led them to a specific technique made with locally available resources that they could add to their instructional delivery or to a targeted activity. Teachers weren’t given more expensive resources to address specific visible or invisible disabilities. They were given a self-reliant approach to problem-solving connected to an observable learning challenge.

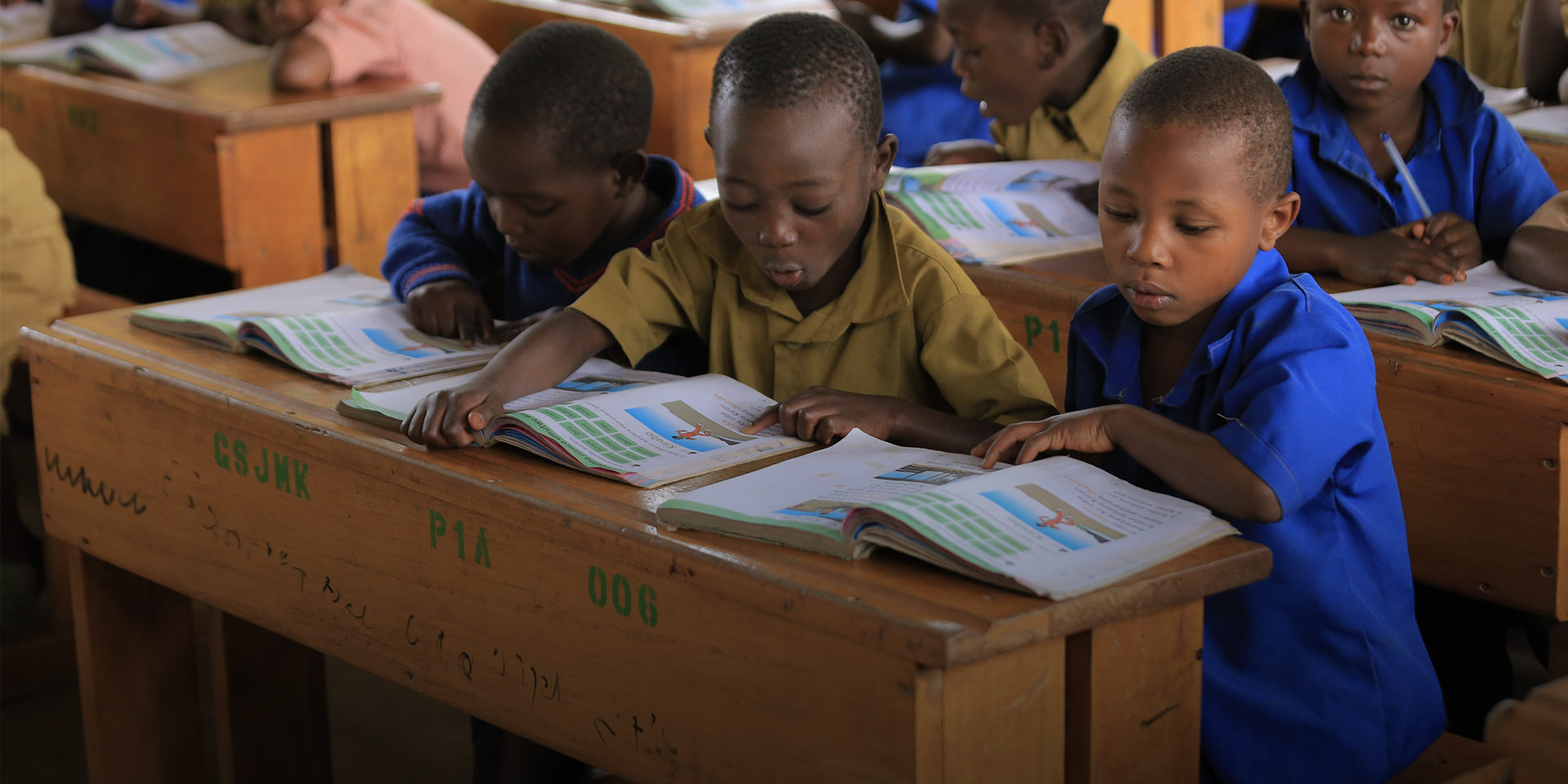

Doing what we can with what we have in each unique country context is core to practical implementation of inclusion in the classroom. In Rwanda, USAID’s Soma Umenye project is rolling out two complementary activities that operationalize Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles in this way. The Kinyarwanda Reading Camps delivered focused remediation to children performing significantly below grade level directly at their instructional level with targeted, explicit phonics lessons and ample time for practice at their independent level with hands-on literacy games and activities. Children demonstrated significant growth, and teachers reported enthusiasm for resources made with locally available materials; they wanted more time to practice using them and shared the desire to use the techniques and activities in their regular classrooms.

Soma Umenye’s UDL pilot supports teachers with techniques that help deliver everyday lessons from the existing teacher’s guide with an inclusive approach. The pilot prepares teachers to recognize typical student challenges in the classroom and to adjust instruction delivery responsively so that all students can participate. Teachers practice judiciously integrating wait time, giving precise cues and clues, prompting student talk and using strategic pairs and grouping, when possible, so that more children can meet the objective of the lesson. Participants note small changes they’ve made in delivery that lead to more engagement with learners of all ability levels. These changes include asking students to act out new vocabulary words rather than the teacher always providing a verbal explanation; sharing a visual schedule with the class at the beginning of the lesson, referring to it throughout so students know what’s coming next; and asking students to work in pairs to identify syllables and target sounds, an activity that involves every student instead of just a few when the teacher calls on them.

Unquestionably, advancing practical implementation of low and no-cost tools and techniques for inclusive education in the classroom is gaining traction with teachers in developing countries. Making small changes through concrete techniques that encourage teachers to deliver scripted lesson plans responsively is the kind of practical support that educators find helpful and motivating and is most likely to lead to positive student learning outcomes while policy evolves and systems strengthen. Chemonics looks forward to collaborations and partnerships on continued efforts that promote inclusive environments where every child has a chance to learn.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.