Disability Measurement Challenges: Not an Excuse to Delay Inclusive Education

April 11, 2019 | 5 Minute ReadAs development professionals, we often get waylaid by measurement challenges in our pursuit of disability-inclusive education. Paige Morency Notario reminds us that when it comes to meeting students’ needs, it’s better to start somewhere than not to start at all.

According to the World Report on Disability, more than one billion people (15 percent of the world’s population), have a disability, and most children with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries have limited to no access to education.

Though staggering, this statistic is likely higher because we have a hard time measuring disability. As a former special educator and a current monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) professional, I feel strongly about the need for improved data to confront this problem and the responsibility we have to support these millions of children without delay. With emphasis on both disability-inclusive education and measurement in its new education policy, USAID tends to agree.

At first glance, data and support may not appear to be at odds — but they often are. As a development community, our desire for data oftentimes leaves us paralyzed, unable to act upon existing needs while awaiting the statistics we think we need to design our most efficient, cost-effective implementation strategy. The Global Reading Network’s Toolkit on Universal Design for Learning to Help All Children Read serves as an important reminder that — while accurate measurement of disability prevalence will help us implement better — we (implementers and host governments alike) cannot withhold services while we wait for quality data. The toolkit also presents Universal Design for Learning as an alternative to our focus on data by redirecting our energy back to students and the support they need.

What are disabilities, and what does ‘inclusive education’ really mean?

The UN defines persons with disabilities as “those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments, which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” However, the definition of disabilities is a social construct — determined by social expectations, which vary from context to context — making this topic all the more complex. That said, a few common examples of disabilities are communication disorders, physical or mobility disabilities, and sensory disabilities (e.g., blindness, deafness).

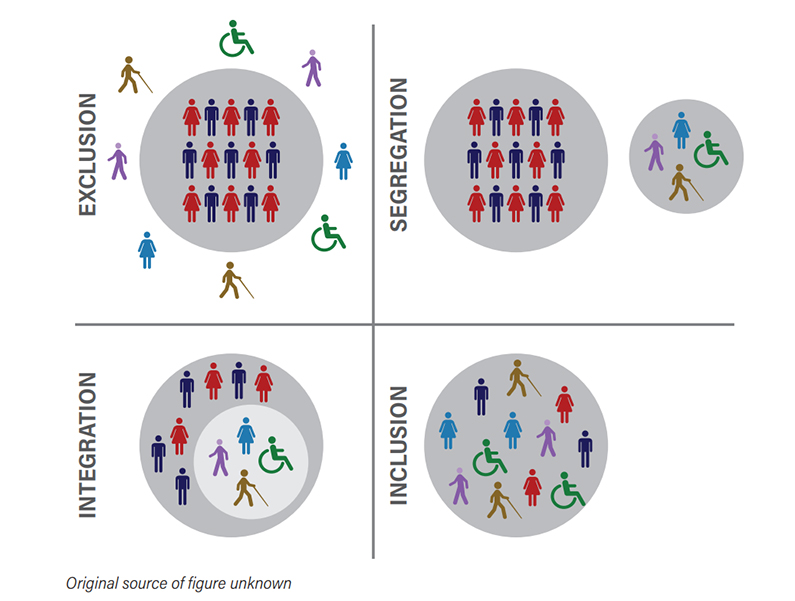

The UN defines inclusive education as “having one system of education for all students, at all levels (early childhood, primary, secondary, and post-secondary), with the provision of supports to meet the individual needs of students.” When serving as a general and special educator, I experienced firsthand how challenging it is to create a truly inclusive environment and how easy it is to unintentionally create an integrated environment. In this scenario, children with disabilities are physically in the classroom but separated either academically or socially from other students. The below graphic from the Toolkit on Universal Design for Learning to Help All Children Read provides a very helpful distinction between inclusive education and other commonly confused concepts.

What are the challenges faced when measuring disabilities?

The most prominent challenge is identifying disabilities in the first place. This, of course, is the most essential first step in measuring disabilities on a larger scale, which would benefit school systems and project implementers alike. However, identification can be very challenging for under-resourced and under-trained teachers, who are frequently looked to for this task. When I was a special educator, for instance, I recall a student struggling to stay focused, causing me to think that perhaps he had attention deficit disorder. However, without proper screening, it’s impossible to determine if the lack of focus was caused by a host of other possibilities, such as hunger, hearing challenges, learning delays, or lack of interest in the material or the way it was presented. Even if a disability is identified, parents may understandably feel compelled to push back against the stigma (and the possibility of lowered expectations from teachers, peers, and others) that frequently accompanies diagnosis. Ultimately, this can negatively impact learning outcomes. Lastly, data comparison is impeded by the fact that there are no universally agreed-upon definitions for disabilities, which means that implementers may be comparing apples to oranges.

What are the possible solutions?

While there’s no quick and easy solution to these challenges, especially in resource-scarce environments, it’s important to remember that starting somewhere is better than not starting at all. By applying the phased approach outlined on page 68 in the Toolkit on Universal Design for Learning to Help All Children Read, schools can begin to identify and address disabilities with routine vision and hearing screenings. They can conduct more intensive screenings and evaluations as resources become available. Most importantly, this approach reminds us that we have an ethical responsibility to couple all disability identification with services/accommodations.

Some recent policies and strategies, such as DFID’s Disability Inclusion Strategy, call for improvements to the evidence base, but most point to disaggregation by disability as the solution to our data problem. Disaggregation will do us no good if we are unable to identify the disabilities in the first place and/or if stigma is so strong that it disincentivizes diagnosis. Therefore, we — as the development community — should ensure that our education programming includes local capacity building in disability identification, its accompanying support provision, and strong community engagement to build awareness and decrease stigma.

However, possibly the most promising solution of all is Universal Design for Learning, which focuses less on identification, and its possibly harmful labels, and more on the children themselves, each with varying support needs that will benefit others in the classroom. The concept of Universal Design for Learning means that shifts towards inclusive education (i.e., changes that make learning more accessible for those with disabilities) actually help all children. It does so by incorporating into instruction:

- Multiple means of engagement (i.e., why students want to learn)

- Multiple means of representation (i.e., what helps students to learn best)

- Multiple means of action/expression (i.e., how a student expresses learning)

For example, as a teacher, I followed the principles of differentiated instruction in an effort to provide multiple means of representation for my students. Some of my students were visual learners, while others learned better through auditory or tactile approaches. To accommodate a student who was hard of hearing, I added more visuals to my teaching. Not only did my student who was hard of hearing benefit from this variety, but so did all the students in the classroom who were visual learners!

In the words of USAID, “Disability-inclusive education improves educational outcomes for all learners.”

As a MEL professional, I fear that without quality data, we risk failing to reach those most in need. We run the risk of wasting both donor and host country government funding if we implement the wrong interventions with the wrong students and/or schools. However, while data is important for creating optimal implementation strategies, implementers and host governments first and foremost have an ethical responsibility to “do no harm.” To me, this means that we cannot use lack of data as an excuse to delay service provision. This also means that we should not open students up to possible labels and stigma by identifying their disabilities without being ready to provide them with the necessary services/accommodations.* Disability measurement is an ongoing challenge, but it is our responsibility as development practitioners to support improvements to this evidence base — while always keeping the well-being and support of students at the forefront — as a necessary step towards effective, inclusive education in schools worldwide.

*For more information, see page 126 of the Toolkit on Universal Design for Learning to Help All Children Read.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.