Redefining Safe Water: A Holistic Approach to WASH

August 28, 2023 | 5 Minute ReadExpanding the definition of “safe” water, sanitation, and hygiene will ensure a more holistic approach that prioritizes secure and safe services for all.

Nearly 1 billion people around the world currently experience water scarcity and the number may rise to 2.4 billion people by 2050. Lack of access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services can expose people to preventable health risks, trigger or exacerbate conflict, perpetuate inequality, and hinder participation in society.

Why is “safe” access important? The U.S. Geological Survey defines safe water as “water that will not harm you if you come into contact with it.” The World Health Organization’s water quality guidelines recommend public health regulations and standards for drinking water, wastewater management, and recreational water. These definitions and guidelines do not fully capture critical aspects of physical security and equity in terms of water access and use, especially for women and gender minorities, youth, people with disabilities, ethnic and religious minorities, people living in fragile contexts, and those vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. As such, definitions based on health and hygiene alone fall short of what is required to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 6 — to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

Two Ways to Adopt a Holistic Approach in WASH Programs

Expanding the definition of safe WASH ensures a more holistic approach that combines health and hygiene targets with physical security and dignity. For implementers and donors of WASH programs, here are two key approaches to keep in mind.

1. Use participatory, locally led approaches to design with inclusion in mind

Interventions to ensure safe access to WASH services must benefit the entire community. To achieve this goal, WASH implementers should consider the unequal power relations and inequalities that individuals experience due to their social identities and use participatory approaches to design programming with gender equity and social inclusion (GESI) in mind. Project teams should engage with local communities including women and gender minorities, youth, persons with disabilities, ethnic and religious minorities, and internally displaced people (IDPs) to understand their needs and priorities and to design interventions that start with social protections to mitigate risk and expand access. By integrating GESI considerations from the outset, program implementers are more likely to identify and address safety concerns that may affect access to WASH for marginalized groups.

Chemonics successfully applied this approach in Tajikistan on the USAID Rural Water Supply (RWS) Activity. Tajikistan is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and ensuring water security for its population is essential for maintaining its stability. At the outset of RWS, the team prepared a strategy to integrate GESI into activity design and implementation and designed a checklist of GESI considerations for each intervention. Throughout the design, implementation, and monitoring of interventions, the activity cooperates with local government officials, water providers, and communities to consider stakeholder needs. Before rehabilitating a water supply system, RWS conducts public meetings to discuss the upcoming project. With an awareness that in some areas women are reluctant to speak in front of men, the activity convenes separate meetings and focus groups for women only to understand their water needs and concerns. In addition to the public meetings, RWS conducts door-to-door campaigns to convey necessary information to each target household.

By involving women in the planning process, the activity incorporates design approaches that address end users’ wants, concerns, cultural perspectives, and hesitations about the improved infrastructure to ensure meaningful inclusion. For example, interventions aim to supply water for each household as individual connections improve safety and save time for women and children who are often responsible for collecting water; in addition, household-level connections improve access for people with disabilities. In addition, RWS established 10 consumer advisory boards to improve dialogue and accountability between service providers and consumers. The boards identify and resolve drinking water issues, promote rational use of drinking water, advocate for water fee payment and metering, and oversee water system performance. As a result of community advisory board members’ efforts to raise funds for new pipes, dig trenches, and connect water meter boxes in Sarikuy village, 7,000 people now have access to a centralized drinking water supply – twice as many as had access to the old system.

2. Use conflict-transformative approaches

The challenge of accessing WASH services is especially acute for people living in fragile and conflict-affected areas who are eight times more likely to lack safe water and sanitation. Further, water insecurity in fragile contexts poses disproportionate health and safety risk for women and children. In a 2019 report, UNICEF noted that children living in fragile and conflict-affected contexts are more likely to die from illnesses related to unsafe water and sanitation than from bombs or bullets. Fragility often disrupts or destroys WASH service systems, and grievances around access to WASH services can fuel existing conflicts or spark new ones. WASH interventions must account for conflict dynamics in their design and implementation. Where possible, WASH efforts should integrate conflict prevention goals, working with governments and communities to leverage WASH interventions to address the sources of conflict and to sustain peace.

A conflict systems analysis on the Yemen Peacebuilding Programme (Josoor) – funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and implemented by Chemonics – revealed that water scarcity was a significant contributor to communal tensions and that demands for water services were a major driver of violence. Based on the Josoor team’s understanding of the conflict drivers, they provided technical assistance and mediation support in both urban and rural areas of the Taiz governorate. In the first phase, the team successfully removed military forces from the water authorities in the city and provided water access to IDPs in the western parts of the city. In the second phase, the team supported the city’s water network to restore water access to some neighborhoods for the first time in more than eight years. Additionally, the team empowered local female mediators to negotiate agreements between conflicting parties regarding access to water basins surrounding the city.

An Expanded Definition Could Lead to Expanded Service

A better definition of safe WASH should encompass standards for health and hygiene as well as physical safety and equity in terms of access and use of WASH services. Such a definition considers not just the service itself but also the surrounding social norms and physical environment. Restricting the definition of safe access to WASH to traditional metrics, such as safe to drink or use, ignores the reality of many. People also need to be safe as they access WASH services and products, which is why we must approach safety at the individual and community level. Listening first to the voices of local community members through participatory activities can reveal underlying power dynamics, perspectives on safety and security, and perceived interactions with WASH services. We can then co-design locally led solutions that represent the diversity in the communities with whom we work. Given that WASH access is not equal, implementers should use a GESI framework and conflict analysis to inform activity design, and work closely with local partners to ensure holistic inclusion in providing access to safe water, mitigate risk to the community, and hold ourselves accountable to protection and safeguarding during implementation. This is what safe access to water and sanitation means and why a comprehensive understanding and application of it is critical to delivering sustainable and inclusive WASH programs.

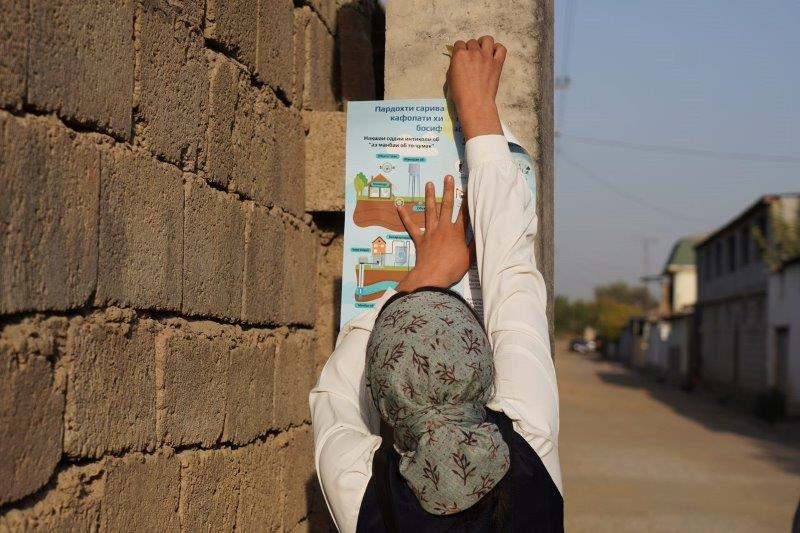

Banner image caption: A volunteer hangs up a poster on the rational use of water in Rudaki district, Tajikistan, 2022. The photo was taken by the USAID Tajikistan Rural Water Supply Activity/Chemonics International.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.