More than Pipes and Pumps: Good Governance Drives Improved WASH

July 1, 2021 | 4 Minute ReadIn a rapidly urbanizing world, how can cities improve governance to meet the water, sanitation, and hygiene needs of their growing populations, particularly the most vulnerable?

We live in an increasingly urban world with infrastructure and essential services struggling to keep pace. From the current level of 56% in 2020, the United Nations (UN) projects that 68% of the world’s population will be urban by 2050. Many of the world’s fastest growing populations over this period are projected to be rapidly urbanizing developing countries, with Nigeria alone expected to add 189 million new urban residents over this period. The joint strain that population growth and urbanization will place on many developing country local governments will be enormous.

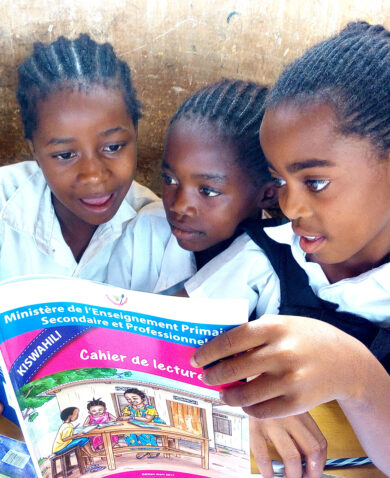

In no sector will these strains be more pressing than in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). Many current and future urban residents, particularly those living in poverty, will have no piped water supply, no hygienic toilet facilities or sewerage, and will lack other vital WASH infrastructure. Weak WASH governance worsens these gaps due to corruption during selection of new settlement areas and failure to prioritize citizens’ WASH needs, exacerbated by weak management systems and limited WASH financing.

These challenges conspire to increase mortality and morbidity from water-borne diseases like cholera and diarrheal disease and lead to other health and development issues for residents of rapidly growing urban areas. The impacts on women, children, impoverished populations, and other vulnerable groups are particularly acute, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened challenges and inequities. The pandemic has also added the new stressor of potentially tighter WASH budgets and has magnified deep flaws in many aspects of WASH governance and local governance overall. It has revealed weak communications, transparency, accountability, and protection of human rights in far too many urban settings.

Without urgent attention, locally defined development objectives and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will remain out of reach. The power of improved governance to rally citizens and government around the cause of improved WASH, to develop urgently needed improved WASH policies and regulations, and to tap innovations in WASH finance and technology are among our most pressing urban development challenges. To move beyond inadequate WASH service delivery, practitioners should support three important overall governance approaches wherever practicable:

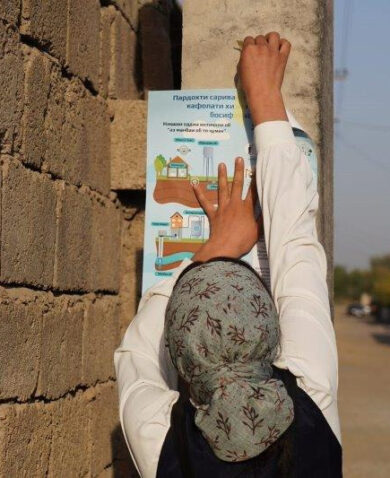

- Urban WASH sectors require an improved social contract and partnership between government and citizenry, with active platforms for learning about citizen preferences paired with monitoring and communications about implementation successes and challenges.

- WASH sector policies, institutions, and processes should be improved to define appropriate implementation, management, finance, and accountability roles for local, regional, and national government.

- Mechanisms for identification, analysis, and scale-up of approaches that support safe and adequate WASH services for all are needed to ensure that vulnerable communities do not continue to be left behind.

Three key urban WASH areas which these overall governance approaches can help advance are improved finance, increased technological innovation, and optimized roles for the private sector.

Improvements in urban WASH finance can drive meaningful coverage and efficiency gains by growing the resource base for urban WASH and strengthening provider financial performance. Deeper understanding of the public and private goods aspects of urban WASH can help better structure and align subsidy approaches and intergovernmental finance mechanisms with the need for local cost-recovery and direct user finance. An earlier Chemonics blog, What Is Needed to Mobilize Commercial Finance for the Water Sector?, explored some of these issues and outlined a three-step finance-based approach for donors to follow to support closing WASH services gaps in low- and middle-income countries.

Improved technologies and their broader application offer the promise of a number of urban WASH improvements. Currently available technologies like point-of-use metering, remote systems monitoring and control, geospatial analysis, and adoption of other “smart infrastructure” improvements can drive efficiency, resilience, and conservation gains, a particularly important direction as climate change and urban growth places local and regional watersheds under strain. During the USAID Mozambique Coastal City Adaptation Project (CCAP), for example, Chemonics helped the rapidly urbanizing cities Pemba, Quelimane, and Nacala use geospatial techniques to develop population, climate, and critical infrastructure vulnerability maps and digital cadasters for urban management. These approaches support more resilient urban service planning and delivery, including WASH. Other advanced technologies like desalinization, water reuse/recycling, nature-based solutions, and the use of Big Data offer the promise of further long-term efficiency and resiliency improvements.

Designing and implementing appropriate roles for the private sector can also help improve urban WASH outcomes and sustainability. Appropriate roles for the private sector must be carefully defined, fostered, and regulated, with due consideration to both important potential efficiency gains as well as the need to maintain safe, equitable, and affordable WASH services as a necessary public good with pro-poor protections. While the private sector is occasionally involved in developing country urban water supply through large concession model mechanisms, these rarely reach poorer populations who reside in more peripheral areas. These newly arrived urban residents are more likely to be served by informal, extremely small-scale private water vendors. And private sector involvement is much less common on the sanitation and hygiene sides of the urban WASH equation. Chemonics has explored a number of these issues for urban services writ large in an earlier blog, Accessing Private Domestic Financing to Improve the Delivery of Urban Services.

In the next entry in this two-part series, we will explore in more detail the role of WASH sector governance as an integrating force for new technologies, improved finance, and optimal roles for the private sector. We will plumb more deeply a number of “blue sky” ideas in these areas and also describe some successful approaches that Chemonics has used to promote better practices and close WASH services gaps. Through this two-pronged approach — identifying and learning from existing good practice and boldly imagining new ways in which innovation can move us forward — we can approach a world where urban WASH services are positive factors for development and for supporting healthier lives for all citizens of our rapidly urbanizing world.

*Banner image caption: A woman and her child fill barrels with water in South Africa.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.