Maternal Mortality Review Committees Ask “Why” to Prevent Maternal Deaths

September 27, 2018 | 3 Minute ReadAbout 300,000 women die during and following childbirth and pregnancy each year. Maternal mortality review committees provide a chance to learn from these tragedies and prevent future deaths by digging down to root causes.

Late one night about a year ago, I got the call no health care worker ever wants to receive. The man left a heart-stopping message with my midwifery practice’s answering service saying that our patient — his previously healthy wife — and their unborn child had just abruptly passed away at another Washington, D.C.-area hospital. He hung up before we got connected; while I know that the circumstances were medically and socially complex, I don’t know to this day exactly what happened.

How Could We Not Know What Happened?

Globally, some 300,000 women die during and following childbirth and pregnancy each year. Even D.C., one of the wealthiest cities in the world, is in the throes of a maternity crisis. Here, 36 women die for every 100,000 live births. That’s twice the United States national average and on par with countries like Georgia, Sri Lanka, and Uzbekistan. These deaths have devastating consequences for surviving children, partners, other family members, and communities. And, most are preventable.

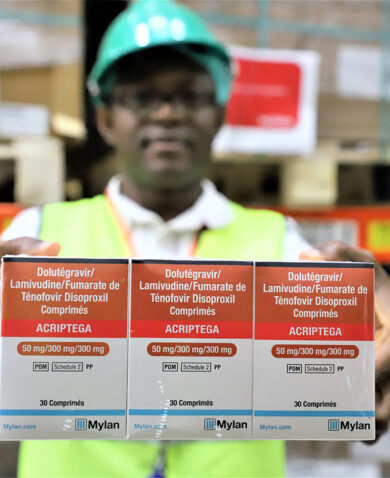

But, if these deaths are preventable, why aren’t they being prevented? The short answer is that because, all too often, we don’t know the root cause of the death. Sure, we know broadly — she had a postpartum hemorrhage, and there was no oxytocin at the clinic to stop it. She had an eclamptic seizure, and her family called an ambulance, but it never came. The midwife at the clinic miscalculated the dosage of antibiotics to treat her postpartum sepsis. Or, she labored for days at home because she didn’t have enough money to pay the hospital bill.

As the number of maternal mortalities has stubbornly refused to fall at the rate necessary to achieve global goals, we’ve come to understand that knowing broadly — putting the “right” interventions and policies into place — isn’t enough. If we don’t know why that essential commodity wasn’t there, why the ambulance didn’t come, why the midwife didn’t give the right dose, or the extent of financial barriers to lifesaving care, we don’t really understand the problem. It’s hard to find a solution if you don’t understand the problem.

Enter Maternal Mortality Review Committees

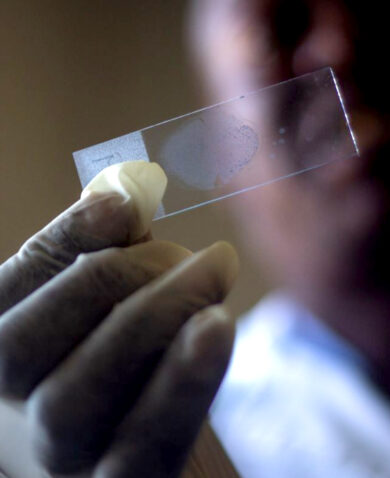

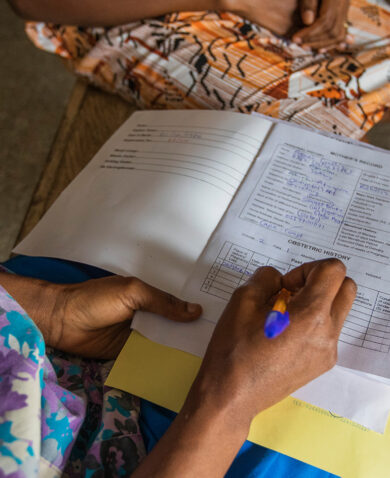

Maternal mortality review committees look beyond just the immediate medical circumstances of a woman’s pregnancy-related death to consider non-medical circumstances, too. This provides a holistic picture of the quality, access, and socio-cultural issues that may have contributed to the death. By systematically documenting these complex issues, we can better understand what went wrong and develop a roadmap communities and institutions can use to make changes to prevent deaths. For example, the global health community believed that increasing the number of deliveries with a skilled birth attendant would lower the number of maternal deaths. Maternal mortality review committees illuminated substandard practices by skilled birth attendants as a driver of maternal death, giving essential momentum to national and global efforts to address quality of care to ensure that health workers are prepared and able to deliver a high-quality standard of care at every birth they attend.

Driven by an urgent need to address its persistent high maternal mortality, D.C. recently passed legislation creating its own maternal mortality review committee. I was among the maternal health professionals who testified in front of the D.C. City Council advocating for creation of this committee. I spoke about my experience working with governments in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia to make these committees standard practice. It’s been exciting to see how once skeptical local and national governments embrace these committees once they realize how committee findings can provide evidence to drive critical policy development or change to save lives. For example, findings have demonstrated the need to standardize drug formulations to reduce dosage miscalculations and expanded access to previously undervalued interventions such as safe blood transfusions.

I also testified about my patient who died last year. In the absence of any formal process to look at the complex circumstances surrounding her death, my colleagues and I remain haunted by it. We missed the opportunity to learn from this terrible event so that we could work to prevent it from happening again, forever left wondering what, if anything, we might have done differently to prevent her death.

No single intervention will end maternal deaths, but maternal mortality review committees hold tremendous potential to inform how interventions are prioritized and implemented, which is particularly important in places where deaths are common and resources scarce. It’s too early to know what we’ll learn from D.C.’s maternal mortality review committee, but I’m proud to see D.C. join the ranks of places around the world that are refusing to accept maternal death as inevitable. However painful the review process can be, it’s not as painful as a preventable death.

Learn More

- Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from Maternal Mortality Review Committees: A View into Their Critical Role. 2017.

- World Health Organization. Maternal Death Surveillance and Response.

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Death audits and reviews for reducing maternal, perinatal, and child mortality. 2018.

Blog posts on the Chemonics blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.