Tragic but Not Unique: Maternal Death in a Rural Clinic

May 5, 2020 | 4 Minute ReadThis maternal health blog sets the scene for a conversation about the challenges of offering quality care in lower volume, more basic health facilities.

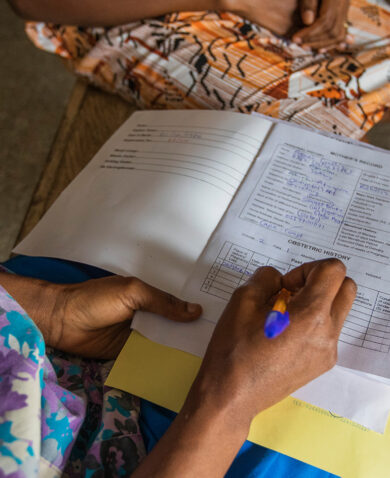

At 1 a.m., Winnie, the midwife at a small health clinic in a rural town in Uganda, was startled awake when the security guard from the clinic pounded on her door—a woman had arrived in labor. When Winnie arrived at the facility, she was surprised to see Clara, a young woman expecting her first baby who wasn’t due for several more weeks. Clara’s labor seemed to be progressing normally, though her blood pressure was high. At 6:30 a.m., Clara told Winnie her head hurt. Winnie gave her paracetamol and encouraged her to drink water. A few minutes later, Clara fell to the floor, shaking. Winnie had been to a training about six months before on management of birth emergencies, and she suspected Clara was having an eclamptic seizure. She ran to the supply closet to get the magnesium sulfate, which she knew could stop the seizure. It took her several minutes to locate it, but she was horrified to discover that she couldn’t remember the proper dose, only that an overdose could cause the patient to stop breathing. She decided to give half the vial and fumbled to prepare the medication. Winnie gave Clara the injection, and the seizure stopped, though Clara remained unconscious. She encouraged Clara’s family to find transportation to the hospital in a larger town an hour way. At 7:30 a.m., Clara’s uncle arrived with a neighbor’s car, and Clara was taken to the hospital. Winnie learned later that day that Clara had another seizure and died just before reaching the hospital, where she gave birth via c-section to a baby boy who died a few minutes later.

Poor quality of care is endemic — and it’s killing women

Clara’s death was tragic — and sadly not unique. The Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems noted that poor quality of care is endemic in low- and middle-income countries and causes more deaths than insufficient access to care. Clara’s story illustrates how women and newborns are particularly at risk, as complications can arise quickly and unexpectedly, requiring a rapid response far beyond what most primary care facilities and providers like Winnie are equipped to offer. But this is a hard truth to stomach after decades spent believing that if we could just get women into health facilities to deliver with a skilled attendant, rather than delivering at home with traditional birth attendants, we could end preventable maternal mortality. Huge amounts of resources were dedicated to ensuring basic emergency obstetric and newborn care was available in lower-level facilities that women could easily access. Clearly, this was not the silver bullet we imagined. The actual quality of care, or the extent to which these services deliver desired outcomes, has not kept pace. Despite this, much of the global dialogue continues to call on expanding access through universal health coverage. So, what should we be talking about?

The elephant in the room: poor provider capacity yields poor outcomes

While quality of care has many dimensions, one important driver of poor quality maternal health care is that many nurses and midwives are ill-equiped or unprepared to deliver it. So far, investments to improve the capacity of midwives to handle complications have not yield broad adoption of international standards of intrapartum care such as active management of third-stage labor to prevent postpartum hemorrhage or monitoring fetal heart rate and labor progress, even when these have been adapted to local context and available resources. This has limited access to safe childbirth for millions of women.

In this scenario, Winnie, despite having been recently trained, missed multiple opportunities to identify and manage Clara’s preeclampsia before it progressed. For example, giving Clara the correct dosage of magnesium sulfate, giving the drug earlier to prevent her developing seizures in the first place, or arranging transport to a higher-level facility that could provide care for high-risk births and a likely premature newborn when Clara first presented signs of complications rather than waiting for her condition to deteriorate. But reaching midwives at the many far-flung facilities like Winnie’s is costly and complicated. She is geographically isolated, and getting to a training site was expensive and pulled her away from her already understaffed clinic. The training was entirely didactic and didn’t include practicing skills such as preparing and administering medications. She also lacks access to internet that would allow for e-learning. While she’s lucky in that she’s received a recent routine supportive supervision visit by local government health staff, it was not used as an opportunity to reinforce new skills, as her district supervisor lacks these skills himself.

Practice makes perfect is key for ending preventable maternal mortality

Perhaps most importantly, and probably under-discussed in the constant drive to expand access to maternal health care, is the fact that, in this scenario, Winnie simply wasn’t seeing enough patients to retain learning and practice skills to confidently manage complications. Preeclampsia occurs in about 2.16 percent of pregnancies and eclampsia in 0.28 percent of pregnancies. Let’s say that if Winnie splits the eight deliveries a month with another midwife, she will attend roughly half of the 96 deliveries a year, making her unlikely to encounter most life-threatening complications; statistically, she might encounter preeclampsia once a year and eclampsia once a decade. Even for more frequent complications, such as postpartum hemorrhage, which occurs in about 9 percent of deliveries in Uganda (though there is significant variation between countries globally), Winnie will only encounter them a handful of times a year. The skills necessary to identify and manage the primary killers of women in childbirth—severe bleeding, infection, high blood pressure—are clear, but require a combination of clinical judgement and skills that have proved surprisingly elusive, until you consider how rarely the many midwives working in low-volume facilities are practicing them.

So where do we go from here? Innovative training approaches such as low-dose high-frequency training — which uses repetitive competency-based training — and simulation training — in which providers practice skills hands-on in teams, sometimes at their clinic sites — have addressed some key issues. But these training resources are intensive and struggle to reach remote providers and ultimately still do not fully address the ultimate issue of “use it or lose it.”

It is time to reconsider the globally accepted system. Shifting services from rural facilities with few deliveries like Winnie’s to busier ones with more advanced care options and skilled providers might help address this issue and save lives, while considering the feasibility challenges inherent in making this shift.

*Winnie and Clara are hypothetical examples based on anecdotal evidence of recurring maternal health scenarios witnessed by our blog authors.

*Banner image caption: Rural landscape in Uganda. Photo by Emma Clark.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.