3 Questions with Juan Felipe Sanchez Franco

March 24, 2020 | 4 Minute ReadA multi-sectoral approach is key to strong supply chains. Juan Felipe shares how this is critical in strengthening the teaching and learning materials supply chain.

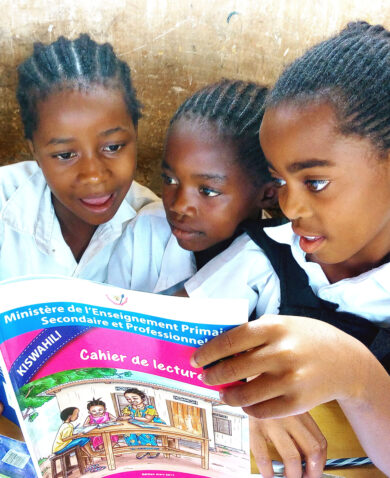

During the past two years, the USAID Honduras Quality Reading Materials Activity (QRMA) Project worked with the Ministry of Education to acquire, print, and distribute more than 3 million teaching and learning materials. Chief of Party Juan Felipe Sanchez Franco offers some insight about the project’s successful collaboration with the ministry and other stakeholders.

How did partnerships with the ministry, the private sector, and civil society contribute to the success of the teaching and learning material distributions in Honduras?

There were three pillars to our success:

- Focusing on participation, collaboration, learning, and long-term capacity building. The first pillar of our success working with the ministry was effectively and consistently using USAID’s Collaboration, Learning and Adaptation and long-term Human and Institutional Capacity Development approaches as a framework throughout the life of the project. As our budget changed, staff had to get creative, and was forced to operate within the public sector’s usual limitations, forcing them to get in the shoes of the ministry and planning and working with the government staff for the long-term with the existing resources.

- Co-designing the project to strategically transition its functions to the ministry. The project team took a facilitative role; we started with more responsibilities and progressively transferred responsibility to the ministry. There were three distribution cycles in the project and by the third cycle the ministry almost entirely took the lead in identifying capacity gaps, forecasting, completing acquisitions, and managing distribution. We transferred the competencies so that our partners, principally the ministry, could sustainably carry out the process, and we followed their own analysis as they identified gaps and came up with solutions to bridge them. This was a key piece of our approach because they were gradually doing both the analysis and the supply chain work, from the beginning of the project, which ultimately resulted in mobilizing 4,400 government staff to deliver 580,000 textbooks to 97.2 percent of the target schools within 30 days of the start of the 2020 school year.

- Adopting recommendations within the ministry instead of filing away the reports. There were many formal adoptions of the newly designed teaching and learning materials supply chain, and we are now in the process of helping the ministry adopt an internal coordination mechanism, which will help institutionalize improved management processes to adopt recommendations for managing, implementing and controlling the supply chain along five stages: development and selection, forecasting and planning, acquisition, distribution, and stock management.

What innovations did you use to distribute teaching and learning materials to the last mile?

Initially, we piloted the use of a track-and-trace platform which required the use of smartphones to scan barcodes on the learning materials to help parents and the community access additional information during distribution. The pilot demonstrated critical barriers for a smooth roll-out such as limited connectivity, especially in rural areas, a lack a culture of smartphone use in some places, limited access to hardware, and the need of intensive training.

In the third and final distribution, we decided to use a combination of technologies to enhance the ministry’s capacity to track and trace textbook distributions. First, the ministry helped us identify a local network of supervisors, parents, and school directors. We encouraged them to use Whatsapp to upload book reception forms, thus building the institutional capacity to coordinate and monitor textbook deliveries. Parallel to this, we started using Tigo, a local mobile carrier, which allowed us to reach parents and stakeholders in the community via SMS and directly ask them whether the teaching and learning materials where available in school. By using these technologies, we had the institutional information that was corroborated by the information from the parents and community confirming that the materials arrived. These solutions were extremely cost effective, and even though we couldn’t use smartphone technology due to constraints at the community level, we still helped the ministry achieve impressive results on last-mile teaching and learning materials distribution this year with 98 percent of the texts confirming that the books are now at the schools.

What were some initial challenges of working with the ministry in Honduras? And how did you overcome these challenges?

The first challenge was that the ministry did not have an integrated, end-to-end concept of a supply chain for learning materials, which is not exclusive to Honduras because this is often viewed as a procurement issue instead of a strategic management process in many countries. At first, the public sector doesn’t always recognize that the supply chain is very complex and requires strategic, multi-sector and multi-disciplinary management. To address this need, the project focused on raising awareness on the complexity of the supply chain, allowing us to secure buy-in from the local government and strengthen its capacity by adopting improved internal coordination mechanisms and processes along the stages of the teaching and learning materials supply chain.

The second challenge we faced was being unable to properly forecast the quantities of teaching and learning materials needed for schools due to highly unreliable enrollment data. We have partially resolved this issue by proactively using data to mitigate gaps and forecasting 10 percent more teaching and learning materials than what the data dictates and gradually reducing our forecasted amounts as we gather more reliable data.

The third challenge we faced was convincing the ministry that developing learning materials requires engagement from other sectors because teaching and learning materials have traditionally been produced and handled by the public sector. It was initially difficult for them to understand that participation from other stakeholders, like the private sector, can also contribute to public education. The project has supported a more participatory approach that encourages the ministry’s interaction with the private sector to develop, produce and distribute teaching and learning materials. We have yet to fully overcome this challenge, but we have made great progress in raising awareness on the importance of engaging all sectors.

*Banner image caption: Stage for a school celebration during a teaching and learning materials distribution in Honduras.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.