3 Questions with Kouteba Al-Khalil on Creating Safe Education Systems for Syrian Girls

October 27, 2021 | 4 Minute ReadUnderstanding the distinct challenges facing girls is central to stopping harm and addressing gender-based discrimination.

![]() The challenge of protecting Syrian schoolchildren predates the ongoing, decade-long war. Before the start of the conflict in 2011, safeguarding practices were rare and legal frameworks non-existent. Physical and psychological abuse as forms of discipline were, sadly, commonplace. In many Syrian schools, these problems persist. In fact, over a decade of intense conflict has exacerbated safeguarding issues. Violence and poverty have psychologically scarred Syria’s young people. Children have been forced out of school.

The challenge of protecting Syrian schoolchildren predates the ongoing, decade-long war. Before the start of the conflict in 2011, safeguarding practices were rare and legal frameworks non-existent. Physical and psychological abuse as forms of discipline were, sadly, commonplace. In many Syrian schools, these problems persist. In fact, over a decade of intense conflict has exacerbated safeguarding issues. Violence and poverty have psychologically scarred Syria’s young people. Children have been forced out of school.

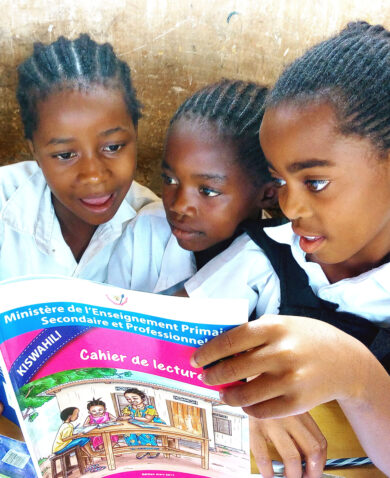

School-age girls in Syria face a complex set of obstacles. Some communities do not value girls’ education. Girls are often required to support their families domestically and financially. Child marriage is increasingly prevalent. Out-of-school girls often cannot access functioning protection systems and are at particular risk of violence.

Chemonics International’s Kouteba Al-Khalil has dedicated his career to child protection in his home country, Syria. Kouteba tells us how the UK aid-funded Syria Education Programme works across schools and their respective communities to provide girls with a safe and quality education.

How can Syrian schools meet girls’ unique protection needs?

Gender-based abuse and violence is a reality for many Syrian girls. Sadly, those able to help victims, namely teachers and parents, are often unaware of the abuse and its harmful effects. Undetected abuse impedes schools from designing procedures to refer children to resources and support and ensuring proper accountability measures are in place.

The Syria Education Programme works to foster safe school environments, preventing and responding to safeguarding issues as they arise. Our approach is multifaceted: providing girls with the means to safely voice their concerns to the school hierarchy and equipping school staff with the ability to proactively and reactively respond to gender-based abuse and violence.

The program teaches girls to recognise different types of abuse and sets up reporting systems enabling them to seek help. Complaints are managed with the utmost discretion to avoid further harm to the child. Survivors receive psychosocial and medical support, while offenders are held accountable. School safeguarding officers forward reported incidents to the education directorate. The directorate is responsible for investigating claims, typically by interviewing witnesses and offenders. They then make disciplinary recommendations based on their evidence. We keep children’s caregivers fully informed throughout the process.

Holding abusers fully responsible for their actions is integral to developing a robust safeguarding culture. However, we also take proactive steps toward making schools a safe environment for girls. For example, our reporting revealed that teachers often discipline girls by yelling at them or moving them to the back of the class; punishments rarely used to discipline boys. This treatment can seriously affect a girl’s school experience and, therefore, their ability to learn. In response, we adapted teacher training to focus on communicating calmly and not resorting to negative discipline techniques, which Syrian teachers often fall back on.

Without such safeguarding structures in place, gender-based abuse can remain undetected and unchallenged. Gender-based violence hinders girls’ short- and long-term progress, impacting their education and life outcomes. Working with both staff and students means we can build a school-wide understanding of gender-based abuse and how to eliminate it.

As well as working in schools, the program works with families and communities to safeguard girls. How do you establish trust and influence within communities?

The success of our safeguarding program relies on community participation. We support communities to take the lead on designing and delivering quality safeguarding programs. Our role is simply to equip them with the support and mentoring necessary to protect children outside of school.

Regular group sessions with caregivers raise awareness of children’s rights and associated protection issues, including gender-based discrimination. These sessions bolster the community’s ability to recognise and reject abusive behaviors. However, more targeted, intensive work is often needed to protect the children most at risk.

The Syria Education Programme’s safeguarding officers hold public meetings with students’ caregivers at the start of each school year, explaining their safeguarding priorities and systems. At each meeting, parents and guardians elect a ‘protection committee’ made up of fellow caregivers. Tasked with identifying at-risk children and working with safeguarding officers to refer them to support services, each committee acts as a focal point for protection work within their local community.

Girls’ needs are often hidden and treated differently to boys’ concerns. Committee members’ intimate knowledge of the local culture and protection issues allow the Syria Education Programme to reach girls who would otherwise be inaccessible to us. Their knowledge enables us to develop culturally appropriate safeguarding policies, making our work less likely to meet resistance or sow distrust. Their input is an indispensable part of our program design process.

How do the community-based safeguarding systems interact with safeguarding systems in schools?

Gender-based abuse and violence occur both at home and in school. If our safeguarding systems are only effective during school hours, then they are ineffective. Maintaining a cohesive relationship between community- and school-based safeguarding systems is critical to protecting children.

Regular meetings between safeguarding officers and local protection committees bridge the gap between girls’ home and school lives. The two groups share information and lessons learned, developing school and community protection plans in tandem. A strong relationship between these two parties helps ensure the girls enrolled in the program are cared for beyond the end of the school day.

The referral mechanisms that direct girls to support services for issues like domestic violence reflect this dynamic. Once the protection committee has identified an at-risk child, they inform the school safeguarding officer. The officer then connects the child to the relevant service. The child cannot attend the service alone, so a committee member accompanies them and their caregiver. They then meet with the safeguarding officer to assess and evaluate the services the child received.

Uniting the different strands of safeguarding means we can enact a singular child safeguarding policy across all our activities. Holding everyone that works with the Syria Education Programme to the same standard eliminates confusion and inconsistency. All involved understand how their work fits into the big picture and how they can best play their part to protect children.

Banner image: Cartoon banner showing three girls smiling against an orange background.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.