Assessing for Success: Education in Crisis and Conflict Environments

March 9, 2017 | 4 Minute ReadIn crisis situations, education services should be provided along with food, water, and shelter. Paige Morency Notario argues that assessment is an essential part of ensuring the success of educational programming in such environments.

The number of displaced persons in the world has reached historic highs, with one out of every four school-aged children living in countries affected by conflict and crisis, where access to education is frequently a challenge. The International Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) states that “funding for education response should be given equal priority with water, food, shelter, and health responses to ensure education provision for affected populations.” Consequently, international organizations are beginning to see education as a basic necessity and universal right, as demonstrated by Sustainable Development Goal 4, which calls for inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all. It also includes target 4.5, which focuses on eliminating gender disparities and ensuring equal access to education. In times of crisis, the value placed on education tends to increase, as schools are frequently viewed as the heart of the community and a symbol of a more hopeful future. In fact, research shows that children in emergency settings, when asked what is most important to them, often respond with “our education.” However, the reach of education extends far beyond fulfilling the basic needs of the individual. Access to education is critical to stability, reconciliation, peacebuilding, and resilience. Timely and inclusive assessments are essential to the success of educational programming implemented in crisis and conflict environments in order to inform effective and context-sensitive decision-making. Chemonics continues to support industry-wide improvements in educational programming in crisis and conflict environments by sharing such lessons learned with the international development community and through its dedicated participation in collaborative groups, such as the Basic Education Coalition.

What does an assessment look like in a conflict or crisis environment?

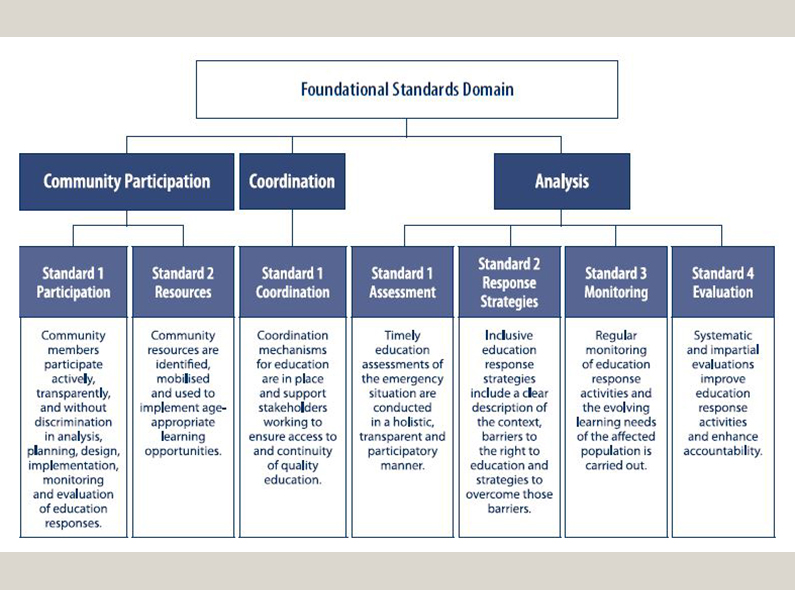

The guidebook, Minimum Standards for Education: Preparedness, Response, Recovery, by INEE lays out the foundational standards to be applied across all aspects of effective emergency education response. One of the key standards states that timely education assessments of the emergency situation should be conducted in a holistic, transparent, and participatory manner. While timely and inclusive assessment is immensely important regardless of sector or location, it is particularly vital to implementation in crisis and conflict environments, as both the activity’s success and safety depend upon consistent monitoring of the ever-changing context and the ability to adapt to the needs of people affected by conflict. Community participation increases accountability, capacity, and long-term support of education services. Additionally, participatory assessment in crisis and conflict environments can lead to the mobilization of local resources, more efficient identification of local education issues, and the appropriate identification of effective education responses.

What are the types of assessments to consider?

Security assessments: Prior to beginning education programming in crisis and conflict environments, it is important to first assess the security of the environments, as well as the safety of implementers and beneficiaries. Chemonics has put security assessments to good use in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in order to safely carry out programming. Members of the ACCELERE! team conducted a mission to Goma in 2016 to assess the needs and identify issues related to security and violence affecting students in centres de rattrapage scolaire (CRS) and centres d’apprentissage scolaire (CAP). The team was then able to adjust their implementation strategies based upon these recommendations, including developing risk reduction plans and localized security plans, with community engagement in targeted schools to mitigate risks to child protection.

Needs assessments: Needs assessments are conducted in order to more fully understand a problem and its context. There are two kinds of needs assessments, rapid or in-depth, and the selection between the two depends upon the particular circumstances and timeline. According to USAID’s Rapid Needs Assessment Guide, a rapid needs assessment for education is needed in three scenarios: acute emergency onset, recent escalation of an ongoing crisis or conflict, and before implementation of a new program design. The purpose of such assessments is to identify education capacities and gaps, assist in the program’s prioritization of support activities, determine the dynamic context in which implementation is to occur, and ensure that programming improves the conflict environment.

Joint assessments: Coordination is key when working in a crisis and conflict environment, in order to reduce the duplication of efforts, more efficiently roll out programming, and share important information with other key players involved in alleviating the crisis. In some cases, a multi-sectoral assessment is possible, which requires coordination with other sectors. When conducting joint assessments, the Global Education Cluster’s Joint Education Needs Assessment Toolkit can be used as a guide. If joint assessments are not possible under the circumstances, the individual assessor should disseminate the findings among other actors in order to provide a coordinated response to the findings.

Reading assessments: Many education programs utilize an early grade reading assessment (EGRA) to inform their implementation strategy, which assesses phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. While complete EGRAs are generally conducted as formative assessments, smaller reading assessments should ideally be conducted on a continuous basis, allowing teachers to adjust their instruction accordingly. Chemonics’ reading projects are an example of both effective assessment, as well as the impact the findings may have on education. The Resources, Skills, and Capacities in Early Grade Reading project conducted an early grade reading assessment and school management effectiveness and safety survey throughout Afghanistan. In total, more than 19,000 students were assessed in 1,265 schools across the country’s 34 provinces. The project is currently disseminating this data through both national and regional workshops for the Ministry of Education’s use in their decision-making and programming. The Sindh Reading Program’s (SRP) assessment activities and analysis in Pakistan led to an official notification by the Sindh Education and Literacy Department to all primary public schools in SRP’s and the Pakistan Reading Program’s 22 target districts to adjust their schedule to include a daily 35-minute reading period.