With this in mind, in 2014 education experts from the USAID-funded Sindh Reading Program (SRP), implemented by Chemonics, conducted a supplementary teaching and learning materials (STLM) gap analysis to catalogue and assess available supplementary reading materials for children in Sindhi, Urdu, and English as part of the project’s focus on boosting early grade literacy in reading and math. They relied on an objective set of criteria to gauge different factors, including quality, appearance, grade-appropriateness, and durability of different supplementary teaching and learning materials.

The exercise was led by SRP technical staff and a reference group of 24 local education representatives: 12 women and 12 men, 17 of whom were native Sindhi speakers. The research team examined 795 books and 46 realia items (flashcards, charts, manipulatives) from 76 publishing houses and not-for-profit organizations. They used a matrix to examine the materials, looking for characteristics and quality standards that reflect current knowledge and practices on STLM and their role in promoting children’s ability to acquire language.

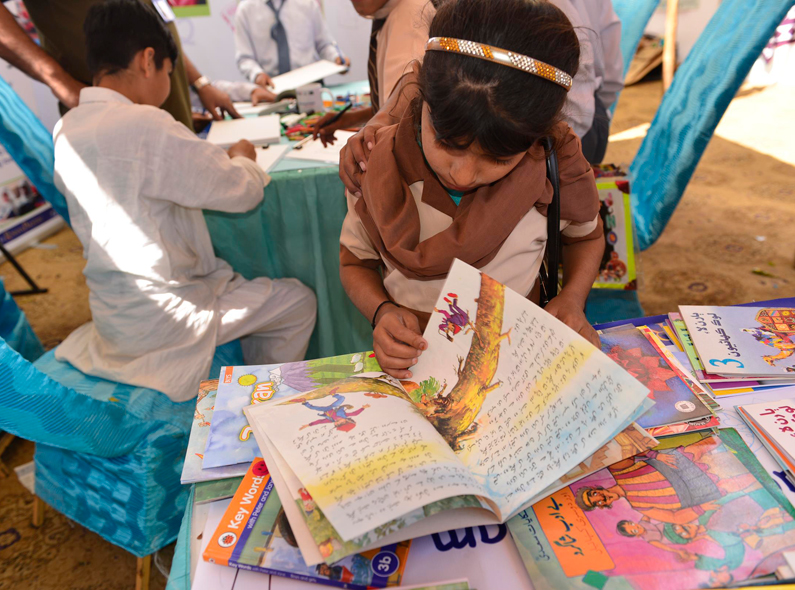

The STLM study revealed some surprising results. There were significant gaps among target age and grade levels in children’s Sindhi literature. And those books that existed did not accommodate the full spectrum of genres that children would encounter throughout their lives. Other dimensions, such as picture-to-word/sentence ratios and the presence of concrete and abstract elements, were also lacking. Although Sindhi-speaking households make up nearly 60 percent of the province, virtually no high-quality reading material in the local language existed for primary grade children. And only a handful of leveled readers existed for older children in grades 5 to 10.

Although the analysis was not exhaustive and couldn’t explain away the low literacy rate in Sindh, it did help shed light on a possible reason that this problem has become so pervasive. Still, it was surprising to some in the education community.

“I thought there was sufficient reading material for young children,” said Gul Badan, an editor at the Sindhi Adabi Board, a government-sponsored institution in Sindh that promotes literature in the local language. “But I realized later that there is a dearth of relevant literature for the younger lot.”

Now aware of these gaps, staff from SRP met with local language publishers to discuss ways to create children’s stories that were more suitable for children in primary grades. Filling gaps in children’s literature titles is not merely a case of translating the content of a book from one language into another language, particularly if the aim of a reading program is to build pre-reading, emergent, and early reading skills for children from multilingual mother tongue backgrounds. Publishers and educators must invest in original, gender-sensitive, culturally-relevant content that improves reading and mathematics skills of Sindh Province children and of Pakistani children more widely.