Safeguarding Women and Girls with Disabilities During Natural Disasters and External Shocks

December 3, 2021 | 5 Minute ReadWomen and girls with disabilities must have a seat at the table when planning for natural disasters and pandemics long before they occur.

Individuals with disabilities, particularly women and girls, have long been excluded from planning and responding to natural disasters, the impacts of climate change, and external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Research indicates that natural disasters and pandemics exacerbate pre-existing inequities, disproportionately affecting women and girls and increasing their risk of violence, abuse, and exploitation (CARE International, 2020, Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2015). For example, women and girls with disabilities are at greater risk of gender-based violence (GBV) because of COVID-19, as they may face increased economic hardship and isolation from support networks through quarantine measures. As the frequency of natural disasters are anticipated to worsen in the coming years due to climate change, failure to proactively plan for the safeguarding needs of women and girls with disabilities places them at greater risk of harm and GBV. Additional intersecting identities such as race, class, gender identity, and sexual orientation further compound these individuals’ vulnerability to GBV and reduced access to equitable healthcare and recovery assistance. By applying lessons learned and practices from the World Institute on Disability’s (WID) U.S. domestic disaster response, development practitioners — in partnership with women and girls with disabilities — can better prepare for and safeguard women and girls with disabilities from future natural disasters and external shocks. In so doing, development practitioners must consider how underrepresented populations, including women and girls with disabilities, are disproportionately impacted by these events and allow them to lead the development and implementation of context-specific safeguarding solutions that best support their needs.

Best Practices

Empower women and girls with disabilities to lead design and implementation of solutions. Women and girls with disabilities must play a key role in planning for disasters long before they occur as they know their own needs best. As such, policymakers and local actors need tools and resources on how to engage women and girls with disabilities in emergency planning initiatives. In the absence of planning, women and girls with disabilities still need to have a seat at the table to ensure technical assistance is inclusive and accessible to them and universal design principles are incorporated. It’s important that they are given the tools needed that provide them accessible means to support their independence. By doing so, women and girls with disabilities are empowered to maintain the health, safety, independence, and dignity of all women and the community at large.

Plan in advance. Advanced preparation can better safeguard women and girls with disabilities during crises, as well as help mitigate their risk of GBV by providing them with knowledge and inclusive tools to identify and access appropriate services. Community disability leaders need to be engaged in early planning efforts, as they can anticipate what problems will arise and how to address them. For example, this might entail developing evacuation information in multiple communication formats, such as braille for blind individuals. It may also include design considerations for sheltering, such as ensuring ramps for people who use wheelchairs. As the frequency and severity of natural disasters is expected to worsen through climate change, it’s imperative that existing projects begin developing inclusive and accessible action plans with women and girls with disabilities leading these planning efforts. This may come in the form of drafting a new action plan or updating existing project safeguarding plans to integrate inclusive disaster mitigation planning from the start. For example, WID is currently working with a major multinational corporation on gap analysis and strategic planning to ensure their climate justice and sustainability priorities are inclusive of persons with disabilities. WID is also working with a U.S. government agency to develop inclusive alerts and warnings, as well as protocols for sheltering in place, and evacuation procedures for employees, contractors, visitors, and others with disabilities who may be affected by an emergency, disaster, or other hazard.

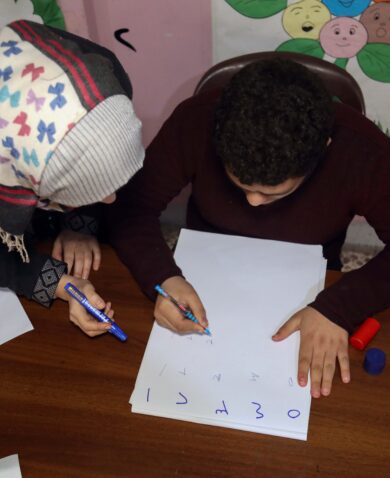

Develop locally focused and context-specific solutions. The needs of women and girls with disabilities vary across contexts. As such WID works with local women and Disabled Persons Organizations (DPOs) to develop locally focused solutions for inclusion. This includes working directly with local women and girls with disabilities to identify their accessibility needs as well as local community resources. WID recently developed the Disability Inclusive Emergency Planning for Disaster Resilience Tool, a comprehensive planning and assessment tool that can be used by businesses, local governments, and schools to identify the requirements needed to optimize everyone’s safety and improve outcomes from future shocks. For example, this may include teaching the community multiple formats for communicating alerts and warnings in case of emergency; providing accessible, actionable information on taking personal protective measures; and teaching women in shelters how to protect children and youth as well as others from GBV including during crises.

Ensure accessibility to and usability of services. Emergency response plans should adhere to universal design principles as much as possible, as women and girls with disabilities may have accessibility requirements that are more specific than the general population. For example, in the instance of GBV, physical accessibility must be provided for women with disabilities to access a safe location and seek counseling in their native language, provided by a native speaker to the extent possible. Pictograms may also be used to assist those with low-level literacy to express what has happened to them and the level of pain they are experiencing. For example, USAID’s Rwanda Duteze Imbere Ubutabera (DIU) project, implemented by Chemonics, increased access to legal services for persons with disabilities by working with the National Union of Disability Organizations of Rwanda (NUDOR) to train legal service providers on the various needs and accommodations of persons with disabilities in providing legal aid. Additionally, WID was joined by Gallaudet University recently to host a series on Deaf Led Disaster Resilience featuring leaders from Viet Nam, Japan, Trinidad and Tobago, Nigeria, Haiti, and Australia.

Instead of

- Consulting women and girls with disabilities in developing safeguarding/emergency action plans.

- Developing emergency planning tools and resources in advance of disaster/external shock onset FOR disabled women and girls.

- Relying on women and OPDs from outside the community in developing locally focused solutions for accessibility and inclusion.

- Developing a one-size-fits-all emergency response plan.

Try

- Allowing women and girls with disabilities to lead planning discussions, set priorities, develop questions, and assess implementation.

- Developing emergency planning tools and resources in advance of disaster/external shock onset WITH disabled women and girls.

- Engaging local women and DPOs in developing locally focused solutions for accessibility and inclusion.

- Developing emergency response plans in adherence with universal design principles and accommodation solutions.

We as development practitioners are obligated to ensure that all people we serve across the globe have equitable access to safe recovery efforts during a crisis. By being proactive and utilizing a participatory planning approach with women and girls with disabilities, DPOs, and other relevant local actors – can we better safeguard their needs during climate change and external shocks, as well as for the entire community. When we get it right for women and girls with disabilities, we get it right for the whole community.

Additional Resources

• IASC Humanitarian Guidance/ Action on GBV

• World Institute on Disability- Global Alliance for Disaster Resource Acceleration

Banner image caption: USAID works with GHSC-PSM to ensure that persons with disabilities are part of the target population for net campaigns and get insecticide-treated nets.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.