Opportunities and enabling factors for thinking and working politically

At USAID, the new Automated Directives System (ADS) 201 guidelines on the program cycle, as presented to implementers, open the door to applying TWP in a meaningful way as part of a push to better take into account local context and apply adaptive management, which includes collaborating, learning, and adapting (CLA). But while some at USAID have recently offered ways CLA and TWP are linked, CLA is apolitical or at least makes no mention of how collaboration could include working with local actors to identify ways of “going with the grain,” or that learning should include context or political economy analysis (PEA) in addition to marshalling the “technical evidence base.” USAID’s Local Systems Framework presents a further opportunity: Systems thinking and TWP overlap in many ways, and an applied political economy analysis can help generate the information needed to plan in accordance to the framework’s principles.

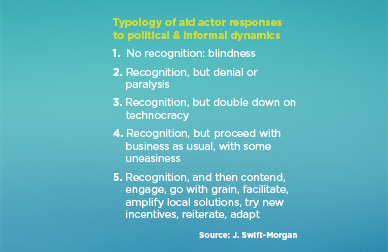

For all of these things, however, implementers depend on what the CLA framework calls the “enabling conditions” to apply these approaches, and depend on where funders fall across the typology of TWP recognition and response. Essentially: Does the project’s scope of work or program description call for a local systems or TWP approach, or aspects of it (such as PEA)? If not, is there room within the results framework and often breakneck timelines, and an appetite among the activity’s managers, to build in TWP and adaptive programming? Is there recognition that risk can be reduced by failing with smaller, iterative attempts rather than failing at the level of a multi-million dollar project implemented at scale from the very beginning with a preestablished design?

The political economy of operationalizing TWP

There are many questions about what TWP looks like in practice, particularly at the project implementation stage after a donor has already decided to intervene in a given context through an externally funded project. In order to be better positioned to try out more concrete ways to do development differently, implementers in these cases require a political economy that includes a few things, such as:

- A mindset shift and higher comfort level both within our own staff and with our funder interlocutors to grapple with questions of power and politics.

- More time and space to articulate project work plans as something that fits into the groove of existing local plans.

- More acceptance for facilitating dialogue and local solutions — that align with or shift local incentives systems — and less direct “doing.”

- True willingness on the part of donors to make real changes along the way, demonstrated and enabled through more flexible contracting mechanisms and agile monitoring, evaluation, and learning plans that measure sustainability as well as any possible immediate impact.

- Incentives, such as might be built into the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System (CPARS), which would reward the application of contextual knowledge and place value on iteration and learning. These would be in addition to the incentives in favor of adaptive programming that donors like USAID are now considering building into project manager performance assessments.

These may be seen as tough asks, particularly given the uncertainties surrounding coming plans for U.S. foreign assistance. But they are the very things that could effectively capitalize on this moment of disruption as we are questioning how development is and should be done — and could ultimately result in greater and more sustainable development gains in the long run.

Aid actors still fall somewhere within a typology of recognition and response to power, politics, and informal dynamics (see box). On one end, some are so focused on the next best fertilizer or medical protocol that they remain blind to the informal dynamics determining whether local actors will take up that breakthrough. Some recognize these dynamics but think the only response is to try even harder to push forward a technocratic solution that somehow steers clear of politics. Others will try to proceed as planned, but with the uneasiness of knowing that politics are influencing outcomes without doing anything about it. Finally, some aid actors do contend with power and politics, engage with these contextual dynamics, and then try to go “with the grain” of local systems as much as possible and aim for “best fit” rather than “best practice” — iterating and trying again as needed.

Aid actors still fall somewhere within a typology of recognition and response to power, politics, and informal dynamics (see box). On one end, some are so focused on the next best fertilizer or medical protocol that they remain blind to the informal dynamics determining whether local actors will take up that breakthrough. Some recognize these dynamics but think the only response is to try even harder to push forward a technocratic solution that somehow steers clear of politics. Others will try to proceed as planned, but with the uneasiness of knowing that politics are influencing outcomes without doing anything about it. Finally, some aid actors do contend with power and politics, engage with these contextual dynamics, and then try to go “with the grain” of local systems as much as possible and aim for “best fit” rather than “best practice” — iterating and trying again as needed.