Next-Generation Urban WASH Requires Transparent, Innovative Governance

August 4, 2021 | 5 Minute ReadEffective governance underpins equitable and efficient service delivery. Explore how developing new and improved methods of governance is critical to addressing the growing challenge of urbanization.

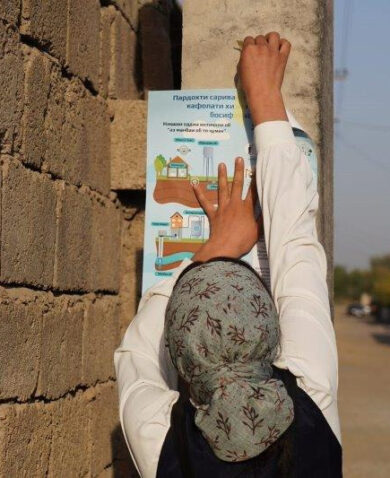

![]() In the first blog entry in this series, More than Pipes and Pumps: Good Governance Drives Improved WASH, we describe how governance is central to meeting the challenges that rapid urbanization poses for provision of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services. In this entry, we focus specifically on how improved WASH governance can enable technological innovations, financial strengthening, and appropriate roles for the private sector to transform urban WASH services.

In the first blog entry in this series, More than Pipes and Pumps: Good Governance Drives Improved WASH, we describe how governance is central to meeting the challenges that rapid urbanization poses for provision of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services. In this entry, we focus specifically on how improved WASH governance can enable technological innovations, financial strengthening, and appropriate roles for the private sector to transform urban WASH services.

Technological Innovations

“Big Data” for improved equity. An increasingly prevalent set of technological innovations in urban WASH service delivery is “smart infrastructure.” One example of this is smart water access points connected to a city-wide WASH internet of things. This promising smart infrastructure improvement can help address issues of inequitable and inefficient service provision. These access points offer real-time, transparent data on use, efficiency, and reliability of water provision at the critical last mile of service delivery. “Big data” from mobile devices, paired with geospatial analysis, can support this approach and allow local governments to understand who is using access points, who is not, why, and, from that learning, deliver more targeted and equitable services.

Although the promise of big-data-supported innovation is huge, it is critical that policymakers, local government officials, and front-line service delivery staff and technicians are aware of and respond to real concerns related to privacy, algorithm transparency, and algorithm equity. Moreover, the less tech-intensive but critically important governance activities of dialogue and accountability between communities, service providers, and local government are essential. These governance activities identify where initial smart water access points should be located, how subsidies and pricing should be established, and monitor the adequacy, equity, and efficient performance of big-data-supported systems.

Partnering with nature. Not all technologies are electronic, and a second promising set of technological innovations centers on harnessing the power of nature-based solutions. These solutions include the use of natural or human-enhanced ecosystems or other nature-mimicking systems for storm water management, water reuse and recycling, wastewater treatment, and sustainable management of watersheds. Nature-based solutions also provide critically important carbon capture, cost management, urban livability, and biodiversity preservation and enhancement benefits. Implementing effective nature-based solutions requires embracing enhanced local governance. This can occur through consultative decision-making on the use of and compensation for environmental assets. It can also take place via intergovernmental dialogue and cooperation related to the use of environmental features, which span local government jurisdictions. Through the USAID Mozambique Coastal City Adaptation Project, Chemonics supported the rapidly urbanizing cities Pemba, Quelimane, and Nacala. These municipalities learned about community-based ecosystem and wetland management and developing local green infrastructure assessments and protection plans. These and other related changes helped partner cities better incorporate city-specific climate challenges into their annual plans.

Financial Strengthening

Financial strengthening is critical to improving WASH services, as rapidly growing urban environments juxtapose immense financing requirements (such as capital-intensive WASH services systems) with increasingly binding financing constraints (budgets stressed by population growth and COVID-19). Despite this difficult starting point, there are promising finance avenues to pursue.

Greater public financing support for WASH. There is a growing awareness of the need for public subsidization of urban WASH services. As the COVID-19 pandemic has unfolded, the world has witnessed the role of inadequate sanitation in individual cities and locales in exacerbating the impact of the pandemic within nations and globally. What is needed on the governance front is intensive policy dialogue and advocacy to build support for WASH commitments and investment with supporting legislation, targeted subsidies, and streams of intergovernmental transfers to make it possible.

Public investment to encourage innovation. Intergovernmental finance can be used not only to support basic WASH services provision, but also to encourage innovative delivery that targets impoverished communities and other vulnerable groups. It can also promote efficiency and reliability of service and reward innovations in the transparency and accountability of WASH services provision. Categorical grants and targeted credit mechanisms could be used to support innovation toward broadly accepted, policy-supported targets. Examples of programs that identify local government service delivery innovations and provide public recognition for them to encourage broader adoption have been emerging over recent years. Indonesia’s Innovation Hubs in East Java, South Sulawesi, and South Sumatra are an example of one successful innovation-identification and recognition approach. Pairing this recognition focus with enhanced public investment and supporting governance work to scale innovations is the next logical step for success.

Diversified streams of finance. Private finance for WASH services can also be encouraged by governance improvements that make local WASH services providers more credit-worthy and their operations more transparent. These improvements include implementing policy reforms and management systems that support increases in efficiency, reductions in cost, and cost-recovery measures that do not conflict with adequacy and equity objectives. The USAID Accelerating Peri-Urban Water and Sanitation Services in Kasai Oriental and Lomami Provinces (DRC WASH), implemented by Chemonics, is embodying these principles and working with local stakeholders to develop Catalytic WASH Finance Facilities (CWFFs). CWFFs, grounded in understanding of WASH services provision and finance ecosystems, are localized institutions that will facilitate financial investments to support delivery of improved WASH services to residents of rapidly urbanizing peri-urban areas.

Private Sector Engagement

Developing appropriate roles for the private sector is crucial for getting more financial resources devoted to WASH. The record on private provision of WASH services has been mixed, though, and several important considerations, cautions, and tradeoffs must drive identification and implementation of effective and equitable roles for the private sector.

Improved governance for private solutions. Due to limited competition among providers, and consumers’ inability to hold providers accountable through voice or choice, private sector WASH services are often priced out of the reach of impoverished communities. Moreover, in cases where price limitations are imposed to accomplish social goals, services are not extended to areas populated by the poor. For private sector WASH services provision to adequately meet the needs of all urban residents, the key governance actions of broad social dialogue on goals, in addition to well-structured regulations and contracts that enforce these goals, must be addressed from the outset. These governance improvements — paired with other public financial management (PFM) and financial market development — are vital because the pool of available private resources is immense. A Chemonics technical brief, Accessing Private Domestic Financing to Improve the Delivery of Urban Services, shares a U.N. Habitat estimate that there is an available pool of more than $89 trillion of private investment capacity that could be tapped to meet urban WASH service provision needs.

Next Steps

The ideas discussed in this blog entry demonstrate several ways that improved governance can harness new technologies, implement new approaches to WASH services financing, and structure optimal roles for the private sector. While there are no simple solutions, these suggestions offer possible pathways for a more holistic, sustainable approach to strengthening governance in light of rapid urbanization. Key research and implementation questions remain, however, to bring these ideas to sustainable fruition:

- How effective, affordable, and equity-enhancing are smart water access points and other “point of service” solutions in reaching underserved urban residents? What features or innovations, technological or otherwise, can boost these key metrics?

- How might existing ecosystem services valuation methods be improved to support establishing interjurisdictional cooperation in the use of nature-based solutions and developing finance approaches and instruments to fund those solutions’ deployment and use?

- In addition to the private sector directions discussed above, how might informal private water vendors be used within formal WASH services delivery systems to support provision of potable water to urban residents? Could “formalizing the informal” be structured such that coverage gains for the poor are realized, the often-exorbitant price-per-volume charged by informal vendors reduced, while adequate-enough returns for private vendors are maintained and their involvement secured?

Addressing these questions and other key research and implementation issues is central to helping solve the critical challenge of providing adequate, equitable, efficient, and innovative WASH service delivery coverage to the world’s rapidly increasing urban population.

Banner image caption: Children wash their hands in South Africa.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.