2. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) will expand quickly into sub-Saharan Africa. PrEP has already proven to contribute to significant reductions in HIV transmission among gay men in Australia, Europe, and the United States. Scaling up PrEP in Africa will be good news not just for men who have sex with men, but also for female sex workers and others who consider themselves at high risk. Unfortunately, poor adherence rates for PrEP have disappointed researchers and clinicians. People seem to be less motivated to take a daily pill when the medicine is used to prevent HIV infection rather than to treat the disease. But, according to speakers at ICASA, help is on the way in the form of many studies to determine the impact and effectiveness of long-acting options, including injectable and implant forms of PrEP. If eventually proven effective and adopted, these medicines could bring unique supply chain challenges, including waste management of syringes for injectables.

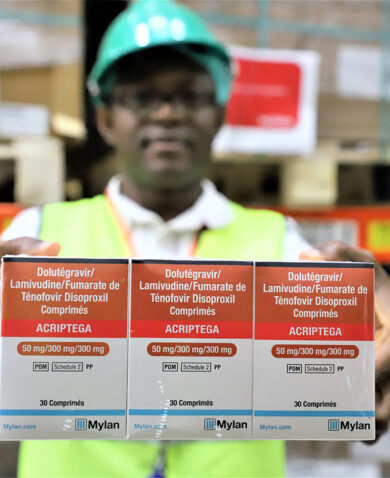

3. The transition to dolutegravir (DTG), a new antiretroviral medicine proven to have fewer side effects and higher antiviral resistance, could be faster than anticipated. Anyone working in HIV/AIDS is already aware of the plans of countries like Botswana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda to transition to tenofovir/lamivudine/dolutegravir (TLD) in 2018. At ICASA, a speaker from WHO shared an extended list for TLD transition this year that included countries like Haiti, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Swaziland. The entire list of 2018 DTG adopters included no fewer than 30 low- and middle- income countries. Although individual countries’ sources of medicine will vary (Brazil and South Africa, for example, can rely on local manufacturers), at some point global demand could potentially outstrip manufacturers’ capacity to produce the needed active pharmaceutical ingredients or finished products. For PEPFAR-supported countries, currently two manufacturers are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to supply TLD, but several more are likely to be approved in 2018, helping relieve pressures on supply.

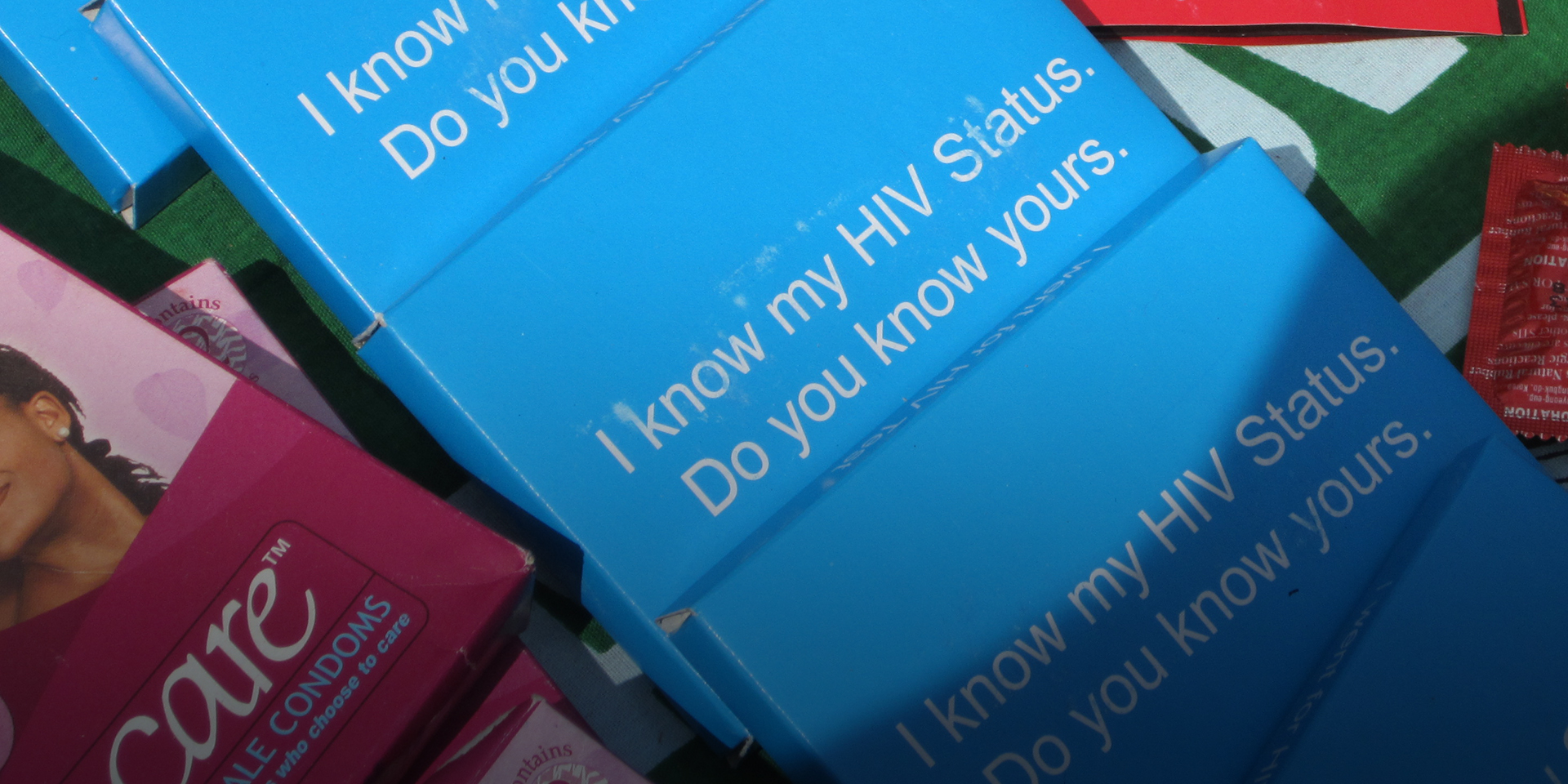

4. Gay men and transgender people and their issues were quite visible at the conference, and many speakers called for an end to stigma against these communities, as well as female sex workers and injecting drug users. An openly gay man was included as a plenary speaker, introduced by a straight ally who gave him an exceptionally warm welcome. What I saw seemed to contradict the news we see so often from Africa of increasing hostility in the legal and political spheres. I asked several gay and straight people who live and work on the continent if social acceptance of LGBTI people is growing. They agreed that, like in the U.S. in the 1980s, AIDS is helping force a grudging acceptance of gay men and transgender women, particularly within the public health community. Only time will tell how much cultural change will happen. There are no direct supply chain implications for this trend, but as more than one speaker at ICASA pointed out, we cannot hope to reach the global 90-90-90 goals for testing, treatment, and viral load suppression unless we focus on reaching those at highest risk. The public health message seems to be getting through.

In fact, each of these trends should benefit the global 90-90-90 goals by increasing the number of people entering testing and treatment. For example, self-testing will not only increase the number of people entering treatment, but is also seen as a gateway to other health services, such as voluntary medical male circumcision. Because people seeking PrEP must first get tested, PrEP programs are helping identify HIV-positive people who then enter treatment. And because the cost of TLD is significantly lower than other regimens, money saved over time can be reallocated for other uses, including increasing the number of people on treatment. No wonder the mood at ICASA was so optimistic.