It’s Complicated: Lessons for GBV Prevention in WASH Programs

December 9, 2022 | 4 Minute ReadThe development community cannot meet its commitments for improving access to safe water and sanitation without integrating safeguarding measures to prevent and respond to GBV.

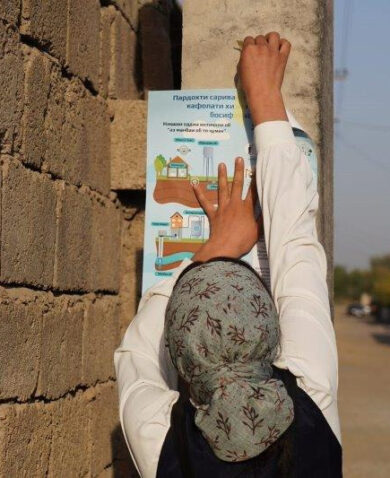

Many women and girls, persons with disabilities, and ethnic and religious minorities experience challenges in accessing safe and clean water and sanitation, sometimes placing them at greater risk of gender-based violence (GBV), which affects one in three women. According to the International Institute for Environment and Development, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) practitioners and policy makers have “inadequately addressed the challenge of vulnerability to violence in relation to access to water and sanitation in development and humanitarian emergency contexts.” Across the globe, Chemonics’ projects are addressing the complex challenges at the intersection of WASH and GBV and have developed best practices to implement safeguarding measures to prevent and respond to GBV in the context of WASH.

Integrate a Gender Lens

It is important to approach the issue of GBV at a systemic level by incorporating a gender lens into both policy and practice. South Africa’s National Faecal Sludge Management (FSM) Strategy, the first of its kind in the country, is a leading example of this. The USAID Resilient Waters project worked closely with policymakers and stakeholders to support the national strategy development process, as well as a case study to build the evidence base for key strategy provisions. Stakeholders emphasized that climate change and gender should be integrated into the strategy, leading to a thorough review of South African legislation on climate change and gender in order to align with the FSM Strategy, while also ensuring that the sanitation strategy did not unintentionally undermine or contravene any of the climate or gender legislation. Building gender and climate into the strategy’s framework addresses these issues equally with the technical considerations for FSM. This also means that sub-national planning and policies are also now addressing these issues. The intention of this process was to ensure that the FSM Strategy, while not a gender-specific strategy and not requiring specific actions related to gender, nevertheless supports national gender legislation.

This alignment ensures that the predetermining factors for GBV are addressed on a systemic level. In working towards GBV prevention, it is imperative to allocate resources, and access to these resources, for sanitation and hygiene before violence becomes an issue. For example, implementation of the future FSM strategy will ensure there are measures in place for safe access to sanitation to decrease the risk of exposure to violence.

Address Access and Safety Issues Directly With Water Service Providers

It is also essential to integrate water service providers at the ground level into WASH programs. This ensures that services as a whole are improved, with safe access for everyone forming an integral part of the work to build capacity, professionalize service delivery and improve financial performance. Our experience has shown that it is all too easy to unintentionally place women and girls at more risk even when the intent is the opposite. For example, expanding the operating hours for village standpipes seems highly desirable, but if these hours of operation mean that water collection can be in the dark then there is a higher chance of violence during the activity. When GBV prevention is built into the activity planning stages, water service providers can hear from their customers and learn about the importance of this prevention.

By supporting water and sanitation service providers and government entities, DRC WASH fosters the emergence of new peri-urban service models. These, in turn, increase communities’ access to safe drinking water and sanitation services. Working closely with the 32 water service providers that DRC WASH targets, the project is also contributing towards GBV prevention. Saidi Byamungu, senior WASH management and finance specialist, notes that this process includes supporting water operators to modify their statutes and internal regulations to integrate gender and social inclusion considerations. Three of these operators have already amended their statutes and two of them have doubled the number of women in decision-making positions. It also includes implementing formal codes of conduct, developing a gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) action plan to prevent GBV, and designating a focal point responsible for monitoring and evaluating the implementation of GESI and the prevention of GBV.

Achieve a Gender Balance to Influence Power Dynamics and Decision Making

To achieve a gender balance in the WASH sector, management and policy must include appropriate gender mainstreaming in the country-specific context. Gender violence does not always result in physical violence. Challenges to women’s equitable participation and leadership must also be addressed through mainstreaming to create lasting change in societies which have traditionally excluded women from the WASH sector. Working toward gender-inclusive policy should occur regardless of the level of existing infrastructure and should be prioritized equally to include women’s concerns and specific needs, and to prevent and respond to GBV in WASH activities.

In Jordan, for example, there are serious sector management challenges due to extreme water scarcity, rapid population growth, poor financial management, and the influx of Syrian refugees. On top of this, there is limited women’s involvement in the WASH sector. To address this, the USAID-funded Jordan Water Governance Activity (WGA) works toward the implementation of the Gender Policy for the Water Sector. This includes direct support to the Gender Unit at the Ministry of Water and Irrigation, the establishment of a gender focal points network in the water sector, the delivery of capacity-building activities, the inclusion of male and female employees in the sector, and gender mainstreaming in sector plans. Additionally, the WGA has spearheaded a National Water Internship Program, which currently has 81 youth interns, including men and women. This program shifts young Jordanians’ attitudes and outlooks on the kinds of work they do and how they can contribute to WASH projects.

Putting It All Together

Development practitioners can draw on the best practices mentioned above to build more inclusive, accessible, and safer WASH systems for women and girls, persons with disabilities, and ethnic and religious minorities. The location, gender-inclusive design, maintenance, and materials can all promote a safe environment for access to WASH. Inadequate access to WASH, or WASH facilities designed without a gender lens are leaving women and girls at risk of GBV and even death. Change must occur on the ground as well as at the policy level, with the integration of women in decision-making positions. In addition to WASH facilities being equipped with materials such as soap, water, privacy, good lighting, ventilation, menstrual products, and so on, it is also paramount that WASH facilities implement safeguarding measures to prevent and respond to GBV when underrepresented groups access water.

Banner image caption: A mentor at the Water Authority of Jordan’s Lab and Quality Affairs offering an intern practical training to help build her skills and advance her career. This is part of the National Water Internship Program for the Jordan Water Governance Activity, which aims to increase women’s equitable participation and leadership in WASH, center the needs of women and girls, and develop projects which prevent GBV. The photo was taken by the USAID Water Governance Activity.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.