The Case for Youth Engagement in the Program Design Process

January 20, 2021 | 5 Minute ReadThe development community cannot effectively design and implement programs for youth without youth at the table. Here are a few approaches to doing just that.

![]() As global development professionals, we need to recognize that today’s world leaders don’t fit the narrow definitions of previous generations. We typically think of leaders as those with long-established power, while we ignore influential, often young, individuals like small-scale farmers and healthcare workers, community organizers and policy advocates. Today, integrating youth engagement in program design and implementation is critical to sustaining development impact over time. Youth-driven interventions focus on the individuals who will shape future policy, enact positive change in their communities, and drive innovation.

As global development professionals, we need to recognize that today’s world leaders don’t fit the narrow definitions of previous generations. We typically think of leaders as those with long-established power, while we ignore influential, often young, individuals like small-scale farmers and healthcare workers, community organizers and policy advocates. Today, integrating youth engagement in program design and implementation is critical to sustaining development impact over time. Youth-driven interventions focus on the individuals who will shape future policy, enact positive change in their communities, and drive innovation.

Global development practitioners must ensure that our programs are driven from the bottom up — by listening to young people and involving them in the process of developing solutions and advocating for their rights and needs. Simply put: we cannot effectively design and implement programs for youth without youth at the table. Here are a few approaches to doing just that.

Start with an Applied Political Economy Analysis

Over the past decade, the development community has come to a tacit consensus: to do development responsibly and sustainably, projects must not only understand the technical aspects of their work but also their own footprint within the local economy. Applied political economy analysis (APEA) is an excellent tool to understand youth as relevant actors impacted by potential programming. A qualitative field research methodology, APEA is used to illuminate the power relations; formal and informal institutions; structural, social and ideological underpinnings; and incentives driving behavior and dynamics related to the focus of study. APEA helps to identify all factors which will affect enacted programming and gain a deeper understanding of local context in a way that informs programming to take advantage of opportunities and navigate risks to be more effective and sustainable.

When it comes to youth-focused development work, field research and discussions with stakeholders provide the opportunity to gather information straight from decision-making sources, such as government agencies in charge of youth-related policy, or industry leaders with the power to influence the direction of workforce development. As development professionals, we should intentionally and holistically represent youth and their unique challenges and opportunities. Conducting an APEA should involve youth in the program design process, informing a comprehensive understanding of the local context and helping determine how stakeholders can work together to enhance design program activities that cater to entire populations, not just the most politically prominent ones.

Give a Voice to Underrepresented Populations

To uncover and understand the full spectrum of youth needs, we need to think beyond formal institutions that often omit certain populations. It is vital to identify all the social groups that the project will target and craft strategies accordingly. Often, we write off “other vulnerable groups” as a catch-all term for marginalized populations and fail to comprehensively support this unseen population. Instead, we should refer to “underrepresented groups,” highlighting that certain identities do not make an individual inherently vulnerable. Rather, external factors, driven by formal and informal social norms, create exclusion and vulnerability. The use of “underrepresented groups” also indicates the existence of multiple groups that should be treated as distinct and important entities.

Moreover, it’s important to move beyond general or blanket language altogether when possible, and instead explicitly identify which groups the program plans to target. Vagueness in language can lead to repeatedly leaving out underrepresented groups. To illustrate this, if programs activities only positively affected two out of five groups, reporting the program successfully reached multiple vulnerable groups through our activities,” while true, does not tell the whole story. Three out of those five groups were still not reached. In contrast, if all five groups are explicitly named as priorities of the program, leadership is held accountable to reaching everyone named during project startup and planning.

For example, homeless youth, orphaned youth, or youth with disabilities are likely to be absent from the education or formal economic sectors, and therefore missing from traditional analyses. Similarly, youth engaged in sex work or other practices perceived as taboo may result in individuals not being “counted” as a part of the studied population. To implement adolescent- and youth- sensitive programming, researchers and technical design managers should work with in-country stakeholders to identify these groups in the local context and leverage their voices to enhance project goals and ensure sustainable impact for all.

Empower Youth and Youth-Serving Organizations

The core of effective development is acting as a catalyst to empower people around the globe to thrive and supporting them to harness their own strengths. This work is especially relevant in working for and with the youth population, who frequently feel disenfranchised and disempowered when it comes to making a difference in their communities, regions, and nations.

One of the critical factors affecting the life of a young person is the policy and legal environment in which they live. Policies and laws can act as either a protective factor or a significant barrier to young people’s health, education, and employment. In fact, 66.5 percent of youth ages 18-29 believe their government doesn’t care about their opinions. As a result, civic participation among youth — whether at the community or national level — may be limited, and youth are often unaware of their fundamental civil rights and responsibilities. Policies and laws can act as either a protective factor or a significant barrier to young people’s health, education, and employment. Research demonstrates that youth who are engaged in the lives of their families, communities, and environments are more likely to become healthy, productive, and engaged young adults. Empowering youth to act as agents of change in their own community will bring about locally sustained change and a more equitable world.

From an economic perspective, getting the global economy on track to reap a demographic dividend, create new prosperity, protect the planet, and eliminate extreme poverty will be difficult unless public and private sectors work together to harness the economic dynamism of youth. Bridging the gap between youth and the private sector can accelerate innovation in products, services, and delivery. For example, Chemonics partners with UNLEASH to provide young entrepreneurs with relevant business frameworks, mentorship, expert insight, funding, partners, and more to support them in identifying and understanding problems in their own communities, developing scalable solutions, and identify the right market opportunities.

As a global development community, we need to commit to embracing youth’s complexity within populations by addressing how different social groups experience society differently. We also need to ensure youth are leading the process because they understand the social structures and sensitivities of their communities to a level an external organization cannot hope to replicate. Using a tool such as APEA, we can thoroughly examine the local context to inform the work we are supporting, and engage youth in a safe space, affording them the opportunity to talk about the real needs of their communities.

Furthermore, we must consider youth populations by gender, sex, sexual orientation, disability status, geographic location, race, religion, education level, and other identities relevant to the local context. We can then consider the impact of these intersecting identities and existing power structures and use them to inform the scope of the project we are designing. To do this, we need to engage young people as a source of change for their own and their community’s development.

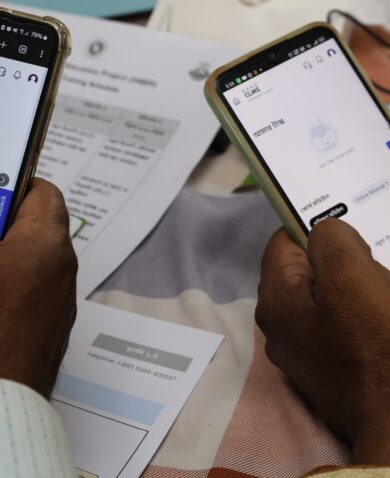

*Banner image caption: Youth participants in the the Human Rights Activity in Colombia.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.