Stop Evidencing Complex Results with Just Numbers and Embrace Narrative

March 30, 2021 | 6 Minute ReadDevelopment professionals often try and track change using just quantitative measures. Yet, words, not numbers, are often the most useful tools in our arsenal when seeking to measure complex change, argues Niki Wood.

‘Complexity’ is a term that we have heard a lot over the last year. The degradation of our climate is a complex crisis. COVID-19 is a complex issue. Everything feels complex currently.

‘Systems’ is equally vogue. Whether talking about doughnut economies or how education impacts resilience, acknowledging that everything operates within fluctuating, interrelated systems is now the norm.

Fashionable buzzwords aside, development actors work within complex systems and deliver complex interventions to address nebulous or ‘wicked’ issue sets with constantly changing and contradictory requirements – like peacebuilding or reducing sexual and gender-based violence. We must be humble about the impact of our interventions in these sprawling systems. Our interventions are a drop in the lake, and we must work to untangle the changes we have actually contributed to from those we have not. Understanding the degree of change we have caused is… well, complex.

Narrative and, more broadly, qualitative evidence are the most valuable tools in our arsenal when working with complex problems. The effects of our interventions are multivariate and often unexpected. We cannot explain everything using just numbers. We need to understand why or how things happen, not just what or how much.

The development industry largely assumes that numeric results are the most reliable results and that narratives are unreliable and vague. The binary nature of quantitative evidence makes it feel concrete or ‘more true’ than qualitative evidence. Using quantitative evidence isn’t wrong; it is a valuable part of evidencing change. However, unpacking our relationship with numbers reveals that the way development actors gather and use evidence establishes reliability, not its countability.

Here at Chemonics, we strive to understand the complex nature of development challenges. Qualitative evidence allows us to identify the conditions for international development success, demonstrate impact, and reveal the unintended effects of actions. By reconsidering narratives’ worth, development practitioners can account for the complexity that characterizes the work we do.

Slippery statistics

Numbers feel great. Humans gain a sense of certainty and surety when looking at a trusty bar graph or pie chart. Yet, we are finding that results and reality are increasingly divorced. We have our neat Results Frameworks with our numeric indicators all showing progress is on-track, yet the results on paper often diverge from the lived reality on the ground.

A report published by The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs is a strong voice in a growing chorus that raises valuable questions about quantitative measures’ limitations. The ministry’s articles show that, perversely, numbers can meet milestones without delivering real change, creating what the author calls ‘paper realities’. When poorly leveraged, quantitative measures can fail to tell the whole story and even miss the mark entirely.

Let me show you what I mean. Cows are 300 times more likely to kill you than wolves. However, if people kept hundreds of wolves on their property and regularly chased them into corral, this statistic would be different.

This anecdote is an example of conditional probability; a concept that many struggle to get their heads around. Statistics need context and careful handling.

A headline result – “83 per cent of people agree crime reduced in their area” – can look good on paper but fail to reflect reality. If the polled population all live in the same place or represent a small sample of the national population, these statistics can become misleading. How you collect and represent your data is important.

Development programs struggle to see the bigger picture when tied to purely quantitative results reporting, even if done well. Numeric data does not reveal causation or indirect consequences. Statistics will offer insights into what has changed, or how much, but not how or why a change occurred. It risks painting a distorted picture of change.

If you are doing something simple like making a meal or, indeed, something complicated like building a hospital, these insights may not matter as much. These understandings do matter when working to address complex or ‘wicked’ issue sets.

The assumption that quantitative data is the most reliable representation of results is a common pain point for programs. We feel the need to count everything we are doing, and, in the process, we do not capture the real change we see. We need to do more than count. We need to leverage qualitative data.

Leveraging qualitative information

We all have this innate assumption that the written word is less reliable than numbers, but as I illustrated above, numbers are fallible too. Words and numbers are the same in this way: it is all down to how you collect, use, and represent them.

The feeling that qualitative evidence is less authoritative mainly stems from the fact that it is not binary in the way that numbers are. The non-binary nature of words does not necessarily undermine their reliability, however. In the right circumstances, it can make words more reliable.

Society — and the actors within it — is messy, convoluted, political, and complex. Development results should reflect this. Improving a sense of safety is not, and never will be, a ‘yes or no’ scenario. Measuring safety is a matter of degrees. People will disagree on what safety looks like and how safe they feel for a variety of reasons. People will disagree about safety in the same way that we have opinions on how tasty pistachio ice cream is.

We need to be comfortable with the range inherent within qualitative results. Their variability matches reality. Their depth fills the gap that the Dutch paper criticized. For instance, if we want to measure if women’s voices are heard more by local government, we must first be sensitive to diverse gender identifications contained with the term ‘women’. Recognizing that different groups of female-identifying people have different concerns and experiences must be the starting point for sound data collection. We must understand what those voices sound like before measuring the degree to which they are heard.

The development community must build results frameworks with qualitative measures that ground our outcomes in the reality of implementation. We need to mix our methods. We need to be honest about the nature of change. Complex change shouldn’t scare us. Qualitative data is something Chemonics International is wholeheartedly embracing.

Complex change in fragile environments

Today, Syria represents one of the most difficult humanitarian operating environments in the world. Despite various complex challenges, Chemonics’ UK Division is harnessing qualitative evidence alongside quantitative to understand how education interventions might impact children’s emotional resilience. The program’s original quantitative method spat out cold numbers to chart children’s emotional resilience. The data failed to capture children’s lived experiences and connect school-time activities with changes in students’ wellbeing.

To make sense of these quantitative results, we designed an evaluation method that drew upon the field of narrative psychology and sensemaking methodologies. The conflict- and age-sensitive approach asked children to share stories about their experiences. ‘Self-positioning’ questioning techniques allowed us to understand the ‘micronarratives’ of these stories; the underlying experiences and sentiments that drove the children’s experiences in and perceptions of their stories. The results were illuminating: the approach meant that the children were empowered to articulate what parts of their story they believed were important and what they felt or thought during various turning points in their lived experiences, without feeling pressured or interrogated. We learned a lot.

Even though the study was a small pilot, the results provided us with the evidence necessary to bridge the chasm between accountable assessment and good delivery. Qualitative evidence gets under the skin of programming. In this case, it made sense of the numbers, shedding light on the meaning behind numeric ‘resilience scores’.

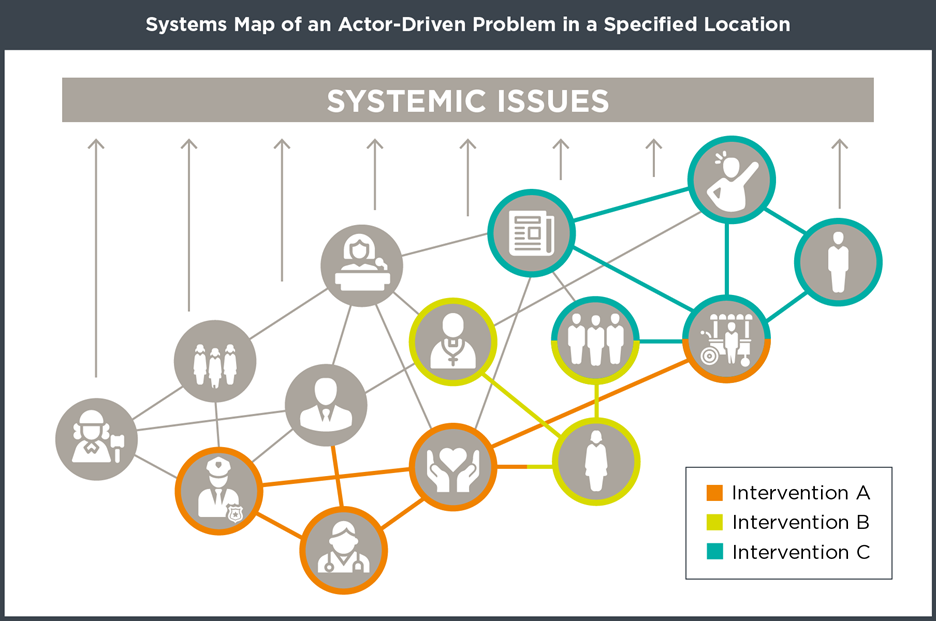

This is just one of many examples of how Chemonics uses qualitative methods. By harnessing ‘actor-based change frameworks’ and behavioral science, we plot and evaluate how people’s behaviors drive systemic and multidimensional issues in conflict settings. With the Institute for Development Studies, we are using ‘governance diaries’ to understand people’s perceptions of government and inform how we adapt accountability programming. We embed ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ tools to support meaningful adaptation. Qualitative data is bringing into focus how our work brings about change and why development matters. By generating meaningful insights, qualitative data allows us to deliver for the communities we serve, not a results framework.

Narrating complexity

As the world gets more complex, we must fight the urge to give in to the satisfying simplicity of numbers. While understanding the what and how much is important, development actors must pull on and trust qualitative evidence to capture the reality of today’s most knotty challenges. To do so, we must mix our methods and not disregard qualitative sources of evidence.

Narratives can help bridge the results-reality divide. Qualitative results can enable us to pinpoint the conditions for success. Perhaps even more importantly, stories can uncover the unintended consequences that inevitably surface when dealing with complex systems and human lives. We can use stories to build evidence about what works and endeavor to ‘do no harm’ to the communities we have pledged to support.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.

*Banner image caption: A teacher in Syria supports her students to draw pictures.