Open and Online Education for All Youth

March 17, 2015 | 3 Minute ReadIn conjunction with the #YouthWill campaign, co-sponsored by Chemonics, Director Sarah Grausz asks what still needs to be done to ensure open and online education really can be a game changer for youth.

Internet connectivity is to us what the internal combustion engine, the printing press, or the compass were to previous generations. It continues to revolutionize our world at an astonishing rate. For the 75 million unemployed youth between the ages of 15 and 24, it offers a means to prosperity and a better life through provision of knowledge, networks, data, jobs, and much more. As our communities and economies integrate and expand with the knowledge economy, and the profound need for skilled labor increases, the availability of quality online education will be a key driver of progress across the globe.

In February on The Verge, guest editor Bill Gates discussed the power of online education to alleviate poverty. Gates predicted that in the next 15 years open online education providers (e.g., edX, Khan Academy, Udacity, Coursera, and others) will perfect their delivery method and drive down the cost of education so that “more and more people have access to the tools they need to take control of their future anywhere in the world.”

Yet some important unanswered questions must be answered before open and online education can reach its potential as a game changer for millions of young women and men.

How can we ensure access to reliable high-speed broadband and electricity?

Countries with high-speed internet access and stable energy supply are more capable of making the transition to a knowledge-based economy. Underused fiber optic networks offer a major opportunity, yet many countries lack the policies and regulatory framework to open this infrastructure to telecom companies. White space technology is being tested as a way to leverage unlicensed areas of radio frequency to carry internet traffic.

How can we create better quality online education?

By 2020, it’s estimated that the global economy will be short 38-40 million college-educated workers. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have mixed results when it comes to completion rates. Then again, completion may not matter as much as we thought. What we ought to care more about is whether these courses help students get jobs. Educators, technologists, and developers must work together to move online education from what some see as “better than nothing” to an intuitive and tailored service that yields higher user satisfaction and employment rates.

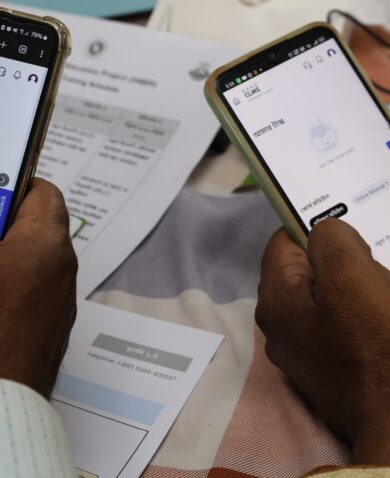

How can we reach the most vulnerable, particularly women, with access to technology?

Access to education for women has the multiplier effect of also decreasing fertility rates, which could enable developing economies to grow more rapidly, also known as unlocking the demographic dividend. Yet open online courses are not easily accessible to those at the bottom of the pyramid, primarily women and other vulnerable groups, who are least likely to own computers or phones, and may also be illiterate. According to GSMA, a woman is still 21 percent less likely to own a mobile phone than a man. This figure increases to 23 percent if she lives in Africa, 24 percent if she lives in the Middle East, and 37 percent if she lives in South Asia. Technology could exacerbate the gender inequity in these regions.

How can we motivate education systems to prepare youth for the jobs of today?

To remain current, established education institutions need to work with the private sector to produce the leaders of the 21st century. For example, huge demand exists for data scientists to mine big data stemming from the spread of web-based technology and cloud computing. When youth begin to have access to analyze big data, they will also be able to guide decision-making and policies at a local and national level.

To realize the full potential that open and online education has for current and future generations, governments and the private sector must invest in skills and infrastructure.

Development partners like Chemonics can add value by delivering a “connective push” in the form of stronger partnerships between youth, educators, and employers.

For example, in Yemen computer skills are some of the most sought-after by the Yemeni private sector, yet few youth have them. Based on the results of our labor market survey, USAID is funding Chemonics and partner Education for Employment to deliver a comprehensive training, internships, and job placements for students, including in computer operation and maintenance, file management, web browsing, word processing, and email. Since last year, we’ve trained 684 youth, placed 578 in internships, and 170 in paying jobs. More than 70 percent received computer literacy training to prepare them for professional jobs.

Whoever answers any one of the questions above is going to improve the lives of millions. My gut tells me that those with the most to gain from leapfrogging the hurdles –youth – will find our solutions. We look forward to hearing their voices throughout the Devex #YouthWill campaign in March and beyond.