Debunking Misconceptions about Universal Design

Universal Design is not a synonym for disability-specific design. It is often assumed that the Universal Design means a product is designed specifically to serve persons with disabilities. That is not the case. Universal Design is not specialized design for one individual’s needs, rather it is easily adaptable based on a user’s preference.

Universal Design is not a product, it’s a process. Universal Design is the process and approach you use to arrive at the goal of producing a widely used and accessible product or space. This consultative process leads to an accessible product that is inclusive of the needs of many as opposed to a select few.

Universal Design aims to be as inclusive as possible, but it does not mean it will serve everyone. Designers may shy away from using Universal Design because of the belief that the design must be 100 percent appropriate and accessible to everyone. Of course, the process encourages the design to consider the needs to as many as possible, but it does not mean the product has the capacity to serve everyone’s needs equally.

Universal Design is too costly and time-intensive and therefore not a practical design model. It is true that the Universal Design approach requires a greater time commitment in the design phase and higher costs upfront. However, this can save time and financial resources in the long run. Rather than being reactive to the needs of every individual when the situation arises, this design approach takes multiple needs into consideration at the beginning, which ultimately saves on costly adaptations that would be required later. To give an example related to accessible spaces, a building that is designed inclusively from the start is usually only one to three percent more expensive than a non-inclusive building, whereas retroactively modifying the building to be inclusive is typically costlier.

In Practice: Using Universal Design to Improve Access to Information

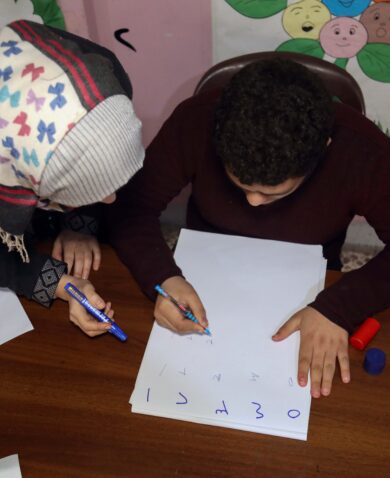

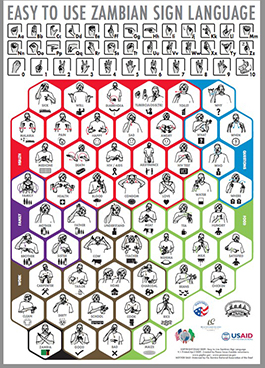

The two most common categories discussed in Universal Design are 1) adapting spaces (e.g., ramps in hotels to assist the elderly and people who use wheelchairs) and 2) modifying products (e.g., a desk that is adjustable for a person who uses a wheelchair). One category that is often less emphasized, but very important to discuss in a development context, is how to design communication to be more accessible to different groups. This can include designing inclusive communication tools for people who are deaf or hard of hearing, people with learning disabilities, or for language minorities.

Symbols and visual images are a good way to provide greater accessibility in public spaces for people with varying language abilities. For example, Zambians who are deaf/hard of hearing lacked awareness and access to information about HIV/AIDS and adolescent reproductive health. U.S. Peace Corps Volunteers in Zambia created posters that incorporated the use of English, Zambian Sign Language, and iconic representations. This combination not only made it accessible to deaf communities in Zambia in their first language, it also ensured those who had no language competencies could readily understand these posters.

In another example, the USAID Vietnam Governance for Inclusive Growth (GIG) Program used Universal Design concepts to publish a Handbook (in Vietnamese) to raise awareness of the personal and property rights of vulnerable groups and provide guidance on how to exercise them. They consulted representatives from international and national organizations and persons with disabilities to make valuable suggestions to ensure the Handbook remained as user-friendly and inclusive as possible by 1) including visual illustrations to aid with comprehension regardless of language ability and 2) producing the handbook in word-format so it is compatible with software for people who are blind to read it.

Universal Design is not an overly burdensome process, and it goes a long way to ensure that different communities have equal access to critical information. If you do not intentionally include, you may unintentionally exclude. Remember to consider inclusion from the start of the design — your projects and the communities you support will reap the benefits for years to come.