What Could the Trans-Pacific Partnership Mean for International Development?

April 28, 2016 | 3 Minute ReadFrenki Kozeli explores the potential implications of the Trans-Pacific Partnerships on global development and the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership is the biggest regional trade agreement in history. Twelve countries representing nearly 40 percent of the world’s GDP — Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam — have agreed on a trade pact that will link their very diverse economies around a set of commitments centered primarily on free trade principles. With one sweep, the partnership could potentially create a uniform set of rules that open market access to all who comply without having to negotiate multiple bilateral free trade agreements.

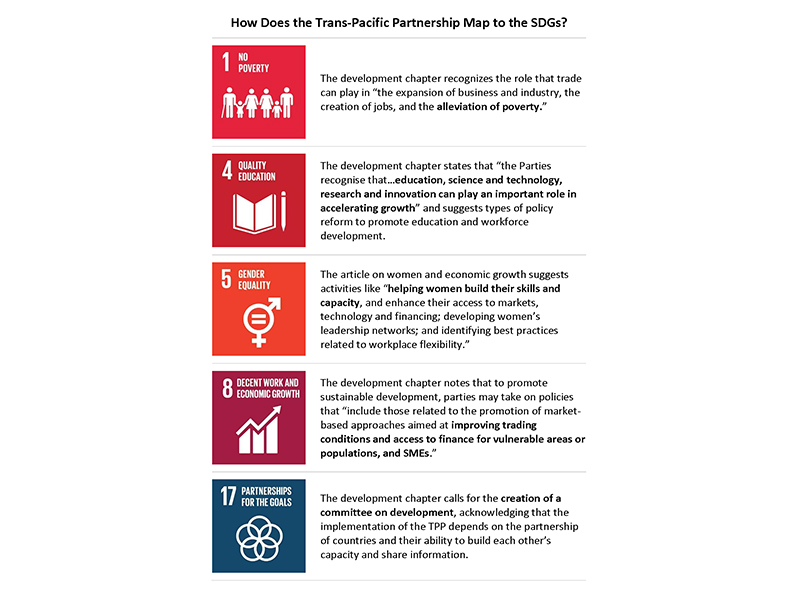

Discussions about the Trans-Pacific Partnership here in the United States tend to focus on its potential impact on American labor, but the partnership also has potential implications for international development. In fact, it is the first U.S. agreement to include an entire chapter on international development issues. The central argument of this chapter is that promoting inclusive economic development internally would allow countries to better benefit from the market access provided by the partnership. It is worth noting that all 12 countries have agreed with this argument. It is also worth noting that the chapter’s emphasis on sustainable economic development echoes the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Trans-Pacific Partnership’s call for creating a committee on development, in particular, opens the door for donor organizations to tailor their programming and partnership with member countries to achieve the partnership’s goals, and by extension, potentially advance some of the SDGs. Digital trade, for example, has the potential to be a great equalizer and source for innovation and employment. The Digital Two Dozen obligations in the Trans-Pacific Partnership include commitments like ensuring access to a free and open internet, allowing open cross-border data flows, and prohibiting digital customs duties. These provisions can reduce the cost of trade and promote entrepreneurship anywhere there is internet penetration, which could provide momentum for targeted technical assistance in IT-focused enterprise development, or in helping governments in making their digital trade regulations compliant with the partnership.

Should member countries ratify the partnership, donors would need to help build a clear pathway for bridging the gap between the partnership’s high standards and members’ capacity in order to prevent the standards from discouraging formal trade. Future technical assistance may center on helping enterprises meet the partnership’s high sanitary and phytosanitary standards, working with governments to reform labor regulations, promoting the inclusive reforms of the development chapter, and a host of other policy and facilitation changes. These changes would have to happen not only to comply with partnership on paper but to take full advantage of the market access the agreement offers. And it would not just be member countries where such changes would need to happen, but also in those aspiring to join.

It is clear that signing the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement was just the first step in what’s sure to be a long process. Each country now, to varying degrees, is experiencing the turmoil of the ratification process. Proponents and opponents have come out in droves. Business associations, unions, legislators, and experts are throwing their weight behind one side or another — at times finding unlikely partners who oppose or support the agreement for different reasons.

Yet many of the goals of the Trans-Pacific Partnership — increased trade, job creation, and economic growth — are goals that most want to achieve, as reflected in the SDGs. Whether or not the partnership becomes the vehicle for those goals, countries around the world will be positioning themselves to better the lives of their constituents, and donor organizations will be positioning themselves to help where needed.

For further reading on trade and development, check out “6 Ways to Make Free Trade Work for Developing Countries” and “8 Ways World Trade Organization Membership Will Benefit Afghanistan.”