Sustainable tourism 2.0

Have we learned from those noble yet unsuccessful attempts to link tourism, poverty alleviation, and biodiversity conservation? Is there a chance to turn the (cruise) ship around?

You bet. First, sustainable tourism businesses need to run in the black in order to contribute to triple-bottom-line results like environmental protection and cultural preservation. That means in-depth market analysis and business planning, strong connectivity to industry partners like tour operators, innovative products and marketing, and world-class customer service developed through specialized training programs.

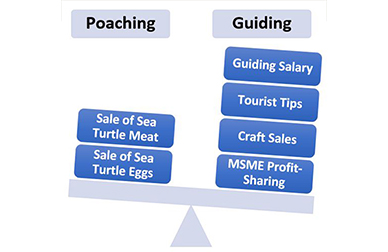

Second, we need to be more strategic in how we design sustainable tourism projects and create direct linkages between tourism job creation and biodiversity threat reduction. As part of the USAID Management of Aquatic Resources and Economic Alternatives (MAREA) project, my work with organizations like Solimar International and Chemonics International included documenting and disseminating replicable case studies that showcase tourism-based biodiversity threat reduction models that included identifying and training sea turtle poachers to transition to better-paying jobs as naturalist guides, developing and branding souvenirs like handbags made out of the same plastic bags littering beaches, and promoting best practices with tourists and codes of conduct with tour operators.

Third, we need to take both a bottom-up and a top-down approach. MSMEs account for over 90 percent of all businesses and 60 to 70 percent of total employment worldwide (numbers that are even higher in emerging economies). Clearly, we need to engage local tourism enterprises to have an impact. Yet we certainly can’t forget about the big guys either.

The World Wildlife Fund’s Global Marine Programme estimates that coastal development, primarily development driven by mass tourism, is second only to unsustainable fishing as the primary threat to the world’s coastal and marine ecosystems. Through internationally recognized certification bodies like the Global Sustainable Tourism Criteria, major players in the industry (including Royal Caribbean Cruises, Airbnb and TUI Travel Group) are adopting environmentally sustainable policies to better manage water, waste, and electricity and reduce their overall footprint. And today, we are seeing such green certification programs not only for hotels, but also for parks, beaches, tour operators, guides, golf courses, marinas, and most recently, vacation homes.