The Refugee Crisis Presents a Global Challenge to the Health Workforce

June 20, 2016 | 3 Minute ReadAs an influx of refugees leads to growing demand for health services, James Griffin discusses strengthening the health workforce in Jordan and around the world.

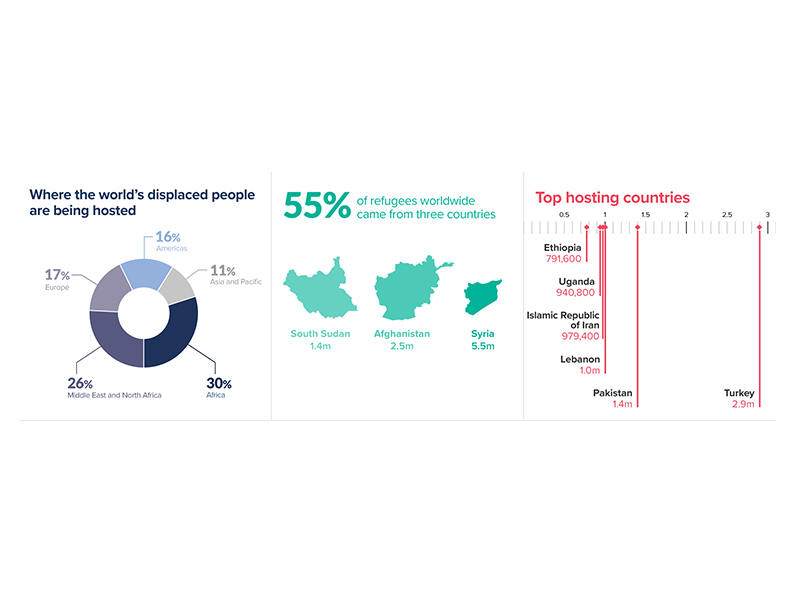

“No one is going home soon,” stated the moderator at a recent Society for International Development-Washington panel discussion about the global refugee crisis. This simple observation drives home the reality that governments, aid organizations, and refugees themselves have confronted around the world for nearly five years. It is a reality that has more recently entered mainstream media and one that continues to confound. 19.6 million refugees — people — worldwide need the essentials, including food, shelter, health care, and safety.

Most critically to the global health community, the stream of refugees has widened the gap between demand for health services and the ability of national health systems to respond. These systems must ensure access to quality health care as a fundamental human right, but the influx of refugees is straining many countries’ health systems, which already suffer from inadequate human resources, to the breaking point.

In particular, Jordan offers a glimpse into the human resources for health challenges faced by countries that bear the brunt of the refugee influx, and what is at stake in solving them. Jordan has a long history of taking in refugees and hosts the second largest number of refugees per capita in the world, at 87 refugees per every 1,000 citizens according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The country’s 2015 census reported 9.5 million people — a significant increase from 5.1 million in 2004. Roughly 40 percent of those, including 614,000 Syrian refugees, rely on the Jordan Ministry of Health for health services.

Yet preliminary data collected by USAID’s Human Resources for Health in 2030 (HRH2030) program points to a significant shortage of frontline health workers in the Ministry of Health’s system. The program also predicts a misallocation of the health workforce between primary care and more specialized facilities. A projected shortage of primary care physicians is troubling given that general practitioners are responsible for delivering most of the primary care services in the country, which can prevent the spread of disease and alleviate the stress on more specialized facilities. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the stress associated with the population increase and refugee crisis is contributing to the public health sector “brain drain” that Jordan is experiencing. In its strategic plan, the ministry suggests that 2.7 percent of doctors and 6.8 percent of nurses leave the country every year.

Countries like Turkey, Pakistan, and Lebanon are experiencing similar problems. For example, in Turkey — the country that hosts the largest number of refugees — clinics and hospitals reported an additional patient load of 30 to 40 percent in 2015. As trends in these countries show, building and supporting human resources for health (HRH) presents an essential long-term strategy for bridging the gap between health system capacity and demand for health services.

In Jordan, the Ministry of Health has moved health systems strengthening and HRH to the forefront. Based on preliminary data, the ministry could consider short-term interventions that would redeploy general practitioners and nurses from hospitals to primary health centers in the regions that have absorbed the greatest number of refugees. In the long term, the ministry and HRH2030 have partnered to institute a more robust in-service training and continuing professional development system that will upgrade the skills of the health workforce while enticing health workers to remain in the country with professional development opportunities. With HRH2030’s assistance, the Ministry of Health is also planning to revamp its approach to supervision so that workers feel more supported and see their performance tied to job advancement. The HRH2030 team and I look forward to addressing these challenges over the next five years and ensuring access to quality health care as a right for all, including refugees.

Though the challenges faced by each country with regard to swelling populations carry their own nuances, we shouldn’t lose sight of human resources for health as a critical piece of the solution around the world. The refugee crisis is about people, and we need good people — skilled, thoughtful, and in the right numbers — to answer the call.