Safe Blood: The Forgotten Commodity for Maternal, Newborn Health

June 12, 2020 | 5 Minute ReadBlood products are critical, but persistently overlooked in the quest for ending preventable maternal mortality. Dr. Adaeze Oreh addresses the need for the global community to act now to combat these issues.

Introduction from Emma Clark, maternal, newborn, and child health technical director at Chemonics

The upcoming World Blood Donor Day on June 14 presents an important opportunity to highlight how critical, yet persistently overlooked, blood products are in the global quest to end preventable maternal mortality. Globally, postpartum hemorrhage — or excessive bleeding after birth — is the leading cause of maternal death. Although the proper use of quality medications can help prevent and manage postpartum hemorrhage, some women will require blood replacement due the amount lost or to underlying conditions. Because of this, access to blood transfusion is considered an essential component of comprehensive emergency obstetric care. Perhaps no one is more familiar with these issues than Dr. Adaeze Oreh, a White Ribbon Alliance Nigeria board member and senior health policy advisor with Nigeria’s Federal Health Ministry. She has spent much of her career working to create blood policies that reduce maternal mortality and reduce the transfer of infections, such as HIV, through unsafe blood transfusions, as well as to improve the distribution of safely screened blood to hard-to-reach areas. As Dr. Oreh lays out so eloquently below, this is an issue that the global health community must seriously address now. In some ways, blood products represent a foray into the new and unknown for commodities projects like the Global Health Supply Chain Program–Procurement and Supply Management project and groups like the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition Maternal Health Supplies Caucus. The commodities community, however, has essential expertise around supply chains, procurement, forecasting, clinical guidelines, and markets that can be applied to blood products to advance access to blood in low- and middle-income countries. Through partnerships like the Maternal Health Supplies Caucus, Chemonics and White Ribbon Alliance — along with many other partners — are working together to highlight need, coordinate activities, and channel expertise to understand and address supply and systems issues to ensure access to blood or blood products for women around the world.

Every minute of every day, a woman somewhere in the world dies during pregnancy or childbirth. Globally, the most common cause of maternal death is bleeding. Without access to life-saving maternal health medicines and supplies, including a safe blood supply to replenish lost blood, a woman — already vulnerable from being pregnant or in labor — can bleed out and die.

For more than 10 years, I have worked in blood services in Nigeria, trying to ensure that life-saving blood from volunteer donors is made available to people who need it, many of whom are pregnant women. My work has often been rewarding: Hundreds of thousands of blood donations made by selfless heroes in my country have saved many lives. In many countries like mine, however, it is still not enough, and so hundreds of women continue to die. Every single day.

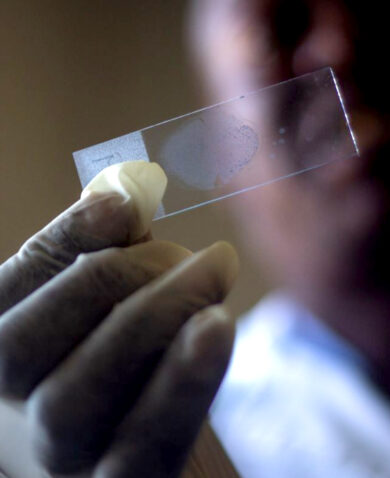

According to data reported to the World Health Organization, while voluntary blood donations have been on the rise in low- and middle-income countries, donors from the African region are lagging. Of the 117.4 million blood donations collected globally, 42 percent of these were collected in high-income countries, home to 16 percent of the world’s population, leaving enormous gaps in available blood for a vast majority of the global population who may need it. Women in pregnancy and labor; children suffering from malaria or sickle cell disease; and victims of violence and armed conflict, road accidents, and trauma — these are just a few examples of those who need safe blood to survive. Aside from numerous myths and misconceptions about blood donations, factors such as anemia, poor nutrition, and malaria prevent many potential blood donors from donating in Nigeria and other sub-Saharan African countries. Coupled with the fact that testing equipment is often unavailable in many low-income settings, access to safe blood is a privilege few can afford.

A Scarce Resource in Demand

In Nigeria, for example, less than 5 percent of blood donations are sourced from voluntary donors; the rest are solicited from patients’ family, friends, or paid donors. Based on Nigeria’s population of nearly 196 million, the World Health Organization recommends a minimum stock of about 2 million screened blood units. Unfortunately, the total blood donations in the country do not amount to half of that. As well, the 2016 United States withdrew foreign assistance for blood transfusion services to countries like Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, and Lesotho, so the situation becomes dire very quickly. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the urgency for safe blood and other reproductive and maternal health services, disproportionately affecting vulnerable families and marginalized communities.

Even before COVID-19, the need for blood confronted women from around the world. Medicines and supplies, with an emphasis on blood, was the number-three demand from the global What Women Want survey, which asked 1.2 million women about their top priorities for reproductive and maternal health services. In many low-income countries, blood donations are sourced during massive blood drives and donor recruitment campaigns in communities and higher institutions. COVID-19–related lockdowns, school closures, and restrictions on public gatherings, however, have severely limited the reliable sources of safe blood. Despite this, blood is still required to save lives.

Taking Action to Make Blood More Equitable

As we celebrate World Blood Donor Day and thank the millions of voluntary and unpaid blood donors around the globe, let us consider for a moment how to optimize their invaluable sacrifice.

First, if there is one thing the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated, it is that a major health threat has the potential to bring everything to a grinding halt. Investing in robust, efficient, and effective health care services should be made from the ground up. National and state governments must provide health financing mechanisms that ensure accessibility and availability of services that begin at the primary health care level and ascend to strengthen district, regional, and national hospitals. For too long, primary health care — which should be the bedrock of our health systems — has been eroding from years of neglect. We are only as strong as our weakest link.

Second, there is no alternative to blood. With all the global scientific advances, no product has yet been developed that can provide all the benefits of blood. National and state governments, therefore, must enable systems that ensure the availability of blood that is safe from the point of collection to transfusion. These include adequate financing, enabling legislation, a skilled workforce, and innovative systems that will guarantee that national and regional blood services have structures, systems, and processes to decentralize and widen their reach to the grassroots. When such systems are in place — as they were in Rwanda during an emergency situation — they can quickly be galvanized for a swift response.

Finally, blood services must be included in the benefit packages of health insurance providers at state and national levels. In Nigeria and many other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, unfortunately, this is not the case. A system where blood and blood products are paid for out-of-pocket by patients and their families is highly inequitable and leaves too many people unable to get the blood they need. There must be universal access to safe blood transfusion,because the quality of emergency services is critical to achieving universal health coverage.

As this year’s campaign says, “Safe blood saves lives,” but that truth can be realized only when safe blood is available and accessible to everyone who needs it.

*Banner image caption: From the “What Women Want” campaign, which asked women for one request to improve the quality of reproductive and maternal services. Photo credit: White Ribbon Alliance

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.