Human Centered-Design: Why Asking the Right Questions is Critical in International Development

August 26, 2015 | 4 Minute ReadAsking the right questions and adopting a collaborative attitude is key to the human-centered design approach to development.

A few years back, I was involved in designing a health promotion and education campaign to help diabetes and hypertension patients take better control of their health in the Caribbean and Latin America.

In Jamaica, I asked my audience a series of questions about their body mass index (BMI) and their blood pressure. In the middle of the conversation, one participant stopped me and made the following remarks: “Sir, why are you so focused on our BMI and blood pressure? We know that we are fat and need to lose weight. So what?”

She went on to say: “I wish you could ask me the following questions: What makes me happy? When was the last time I was happy? And what will it take to make me happy again?”

Needless to say, I was completely unprepared for her questions, and caught off guard to see the tables turned.

My first reaction was: How do I measure happiness? How can I design a health promotion message about diabetes and hypertension without talking about BMI, blood pressure, and weight management?

Then it occurred to me: I had simply failed to ask the right questions.

So, how do we know what questions are the “right” questions? Are there any tools available to help development practitioners ask the right questions?

The concept of human-centered design, championed by the design firm IDEO, calls for three fundamental steps: inspiration, ideation, and implementation. The inspiration phase is the chance to culturally immerse ourselves in research participants’ environments to better understand their needs. In the same fashion, the ideation phase helps us draw lessons learned from participants to explore solutions and co-create prototypes that are culturally aligned with their vision and ideas. This sets the stage to the implementation phase, where solutions are adopted and shared with the general public for feedback and review.

What this means in practice is that one has to adopt a “Curious George” attitude and ask questions to get the wheel of human-centered design moving.

In Jamaica, though my research participants and I had similar goals to improve their health outcomes, we had different ideas about how to go about it. I quickly learned that focusing on measuring BMI and blood pressure was not going to get me anywhere. Furthermore, the nature of my research participant’s questions made me realize that my audience was more interested in developing a health promotion campaign that took into account their entire well-being and state of mind — not just their physical markers. It dawned on me that they wanted to talk about their health challenges from a position of strength. Finding what makes them happy could put them in a much better mood and position to address any health issues that they were facing.

A good understanding of human-centered design allows us to be humble and respectful of diverse opinions — and, above all, validate people’s concerns and wishes. It’s a concept that meets people where they are. Equipped with such knowledge, I decided to collaborate with my research participants and engage them in a collaborative process. That process started with building trust. I went ahead and devoted a big portion of our interaction to talking about well-being and happiness. I also asked them to define “happiness” and “health — to put them in the driver’s seat and work from a definition of health that made sense to them.

“What makes me happy is to see my children graduate from college. I am looking forward to seeing my baby girl graduate. It is the biggest accomplishment in my life,” said the woman who had initially interrupted me.

Feeling a sense of accomplishment through her children’s own academic success is what mattered the most; not her BMI. Creating a space for my research participant to define health and wellness in her own terms gave me the chance to build trust. Furthermore, I realized that for her, health was not the presence or absence of a disease, as defined by some public health professionals. In this case, wellness and academic success were driving forces that brought joy to her and more broadly, her community.

“I am aware of my BMI and blood pressure,” she said. “Talking about it does not make me happy. But I know I have to do something about it.”

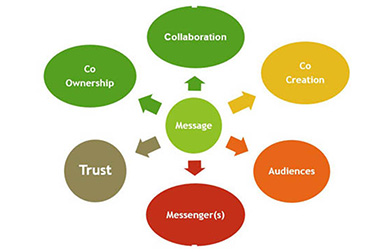

My research participant’s story helped me develop a model (right) that I have used since then to make sure that I am asking the right questions. It starts with building trust and empathy, and developing a strong sense of collaboration between investigator and research participant. This helps set the stage to co-create a message — to design a program with people, rather than for them. In this case, the original message was about health promotion, but after listening to the voices of the participants, the message became more focused on wellness and academic achievement.

My research participant’s story helped me develop a model (right) that I have used since then to make sure that I am asking the right questions. It starts with building trust and empathy, and developing a strong sense of collaboration between investigator and research participant. This helps set the stage to co-create a message — to design a program with people, rather than for them. In this case, the original message was about health promotion, but after listening to the voices of the participants, the message became more focused on wellness and academic achievement.

Finding the right audiences for the message is equally important. In this case, the woman’s daughter, and by extension, the extended family and community had to take center stage. The incentive for getting on board with any health promotion program had to be linked to her greatest need: to see her daughter graduate.

Being able to ask the “right” questions is the most challenging phase when using a human-centered design approach in the international development arena. As development practitioners, we face this challenge on a regular basis, trying to balance our academic training in areas such as epidemiology or bio statistics with understanding the complex and rich cultural contexts in which our research studies are being conducted.

Engaging research participants in a culturally appropriate manner that allows them to take the lead in defining key health and wellness concepts, within their own cultural lenses, can lead to a productive collaboration that is mutually beneficial to all stakeholders.