Achieving 90-90-90 – with Lessons from the 90s

July 18, 2016 | 3 Minute ReadAs the 2016 International AIDS Conference kicks off in Durban, Mary Lyn Field-Nguer of USAID's GHSC-PSM project reflects on lessons learned and the future of HIV/AIDS programming.

Last week I sat in a workshop about expanding access to treatment for all people living with HIV, regardless of their clinical stage or CD4 count, and remembered my early years working on HIV programs in sub-Saharan Africa. As I reflected on how far we’ve come, I thought about some of the biggest lessons I have learned over my career and how we can apply them to challenges going forward.

When I started out, the HIV budget for a large country in Africa was just $200,000 – $400,000, and there was no such thing as HIV testing, counseling, or treatment. Approaches included STI diagnosis and treatment, policy work, condom social marketing, behavior change communications, and evaluation. Due to budgetary constraints, we couldn’t always do what we knew was best. It is ironic that people say “prevention did not work,” given the meager resources invested before treatment was feasible. It was painful to have to choose between condom social marketing and STI diagnosis and management, when it was so clear that an impact would only result from a combined approach.

Today, we have a multi-billion-dollar budget for all aspects of HIV. Combine with that the tremendous advances we have made in biomedical interventions, and we are better positioned to defeat HIV/AIDS than at any point in history. As I begin work on a global supply chain project to support 90-90-90; fast track, treat, and start; or whatever you want to call it, I am optimistic about the role we can play in ensuring that the necessary drugs and equipment are available to treat people living with HIV in some of the world’s poorest countries.

At the same time, I am hopeful that there will be ongoing support for the critical non-biomedical programs that are vital to the success of treatment scale-up. I believe there is a risk that treatment for all will not succeed in leading us to an AIDS-free generation without programming with the following lessons in mind.

Stigma and discrimination can undermine sound biomedical interventions. Without attention to how health care workers treat people with HIV, how people with HIV feel about themselves, and whether families and communities support or shun them, the most accessible viral load instrument, and the most efficacious treatment regimen will not be sufficient.

Community and family support are essential for HIV treatment to work. The degree to which people with HIV seek testing and treatment, and then stay on treatment, depends greatly on communities encouraging and supporting them. This can only happen once they disclose, and this, again, depends on lessening stigma and discrimination so they feel safe to do so.

Ongoing HIV education and community mobilization are foundational to a decrease in stigma and discrimination, to decreasing transmission risk, and promoting treatment adherence.

The bottom line is that there is no magic bullet in the world of HIV. Well-funded biomedical interventions, no matter how advanced the science, can’t solve the problem alone. Without some basic understanding of HIV by communities and youth who are becoming sexually active, stigma and discrimination, unsafe sexual behaviors, and the barriers that impede treatment will persist. On the flip side, it is unrealistic to expect that behavior change communication or other prevention initiatives will solve the problem without universal access to treatment.

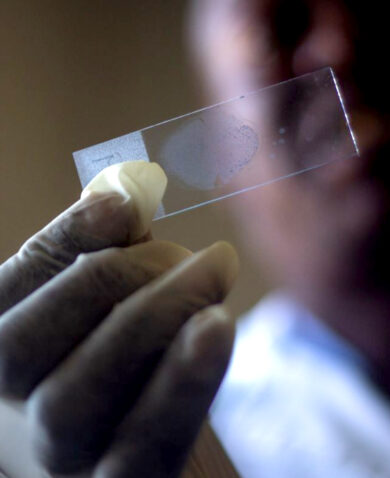

And, of course, without reliable supply chains, the drugs, diagnostics, and monitoring equipment and supplies needed for these treatments will not be available.

I feel privileged to have worked on HIV from the days of national prevention programs on shoestring budgets to today with the billions at our disposal. I firmly believe that the way forward now rests in the collaboration and synergistic efforts of host countries, implementers, and donors to pursue a broad strategy that encompasses biomedical and non-biomedical approaches.

Above all, our efforts should be grounded in mutual respect for the wisdom brought by diverse disciplines – from anthropology to immunology to logistics – all leveraged to reach the goal of an AIDS-free generation.

This post also appeared on the Digital Hub of the 2016 International AIDS Conference.