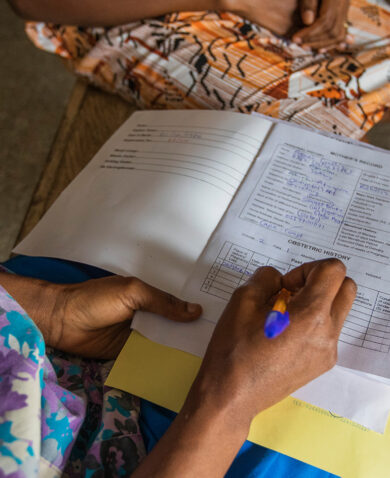

3 Takeaways from Testing the Gender Competency Framework in Ethiopia

April 7, 2020 | 3 Minute ReadHow do family planning service providers consider gender when counseling their clients? Here’s what HRH2030 learned in Ethiopia.

This post was adapted from a post that originally appeared on the USAID HRH2030 program’s website.

Gender sensitivity is often overlooked in the slew of daily health care inquiries directed to service providers. And yet, gender norms—how a society ascribes day-to-day roles, rights, and responsibilities to women and men—play a significant role in client-provider interactions. Reproductive health or family planning providers, in particular, have the potential to be change agents in the area of gender equality. By high-offering quality, gender-sensitive, transformative services, they can enable clients to make voluntary and informed decisions about their family planning needs, improving both gender equality and reproductive health outcomes.

After validating the Gender Competency Framework for Family Planning Providers in the Philippines last year, HRH2030 sought to add to the global understanding of gender competencies in family planning services. Ethiopia emerged as a particularly interesting place for this exercise. For one, the government of Ethiopia had already begun to advance similar priorities. An objective of their 2015-2020 Health Sector Transformation Plan is to develop “Compassionate and Respectful Care” by providing person-centered care with empathy and facilitating the participation of patients and families in decisions and care.

The project team met with providers and stakeholders in urban and rural, public and private, and large and small facilities to discuss the domains of gender competency. The feedback we received will be compiled with that from the Philippines and used to revise and update our Gender Competencies Framework for Family Planning Providers resources. Here are our top three takeaways:

1. Gender competence is for everyone.

Our gender competency framework is meant to guide midwives, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and community health workers when discussing family planning. But in Ethiopia, we were reminded that high-quality, accessible health services encompass more than traditional health worker cadres. Guards, receptionists, and cleaning staff at health centers also play an important role in providing equitable services. It is important for all members of the health facility staff to demonstrate gender-sensitive communication. If an unmarried woman’s first impression of a health facility is someone saying, “Why are you here, you’re too young for this!” she is unlikely to feel comfortable discussing her family planning needs, even if the family planning provider she sees is gender competent.

2. Community-based health workers have unique opportunities for engaging men and boys.

One of the six elements of gender competency for family planning providers is engaging men and boys as supportive partners and users of family planning, while ensuring women’s rights in the decision-making process. On the global level, research shows that engaging men can play a key role in accelerating global family planning goals such as Family Planning 2020. In Ethiopia, providers noted that there are many myths circulating around family planning methods and that, as a result, it is common for men to prevent women from making decisions to use or not use family planning. They also shared stories of women asking for early implant removal because their husbands did not approve. By engaging men and boys, myths could be dispelled, and voluntary family planning could become a shared responsibility.

But, providing information to men and having them involved in discussions about family planning can be challenging especially if they are not coming into health facilities for family planning services and information. In Ethiopia, many of the facility-based nurses, midwives, and doctors we spoke to shared that their family planning clients were 99 percent female. However, Ethiopia is also unique in that it has formalized its community health extension program Health Extension Workers (HEWs). One bright spot shared by providers and stakeholders we spoke to in Ethiopia is that HEWs may expand the number and type of conversations family planning providers have with men and even couples about family planning at the household level.

3. Complex health situations require nuance for effective gender approaches.

Another critical element of gender competency for family planning providers is addressing gender-based violence (GBV). This is one of the most challenging areas of focus because each country’s health system has varying levels of sophistication and readiness to consider GBV. For example, when we first field tested the framework in the Philippines, the content of the GBV domain resonated with providers and the existing systems for GBV. While many providers shared that they did not feel they had adequate training on GBV, they still recognized it and could discuss the interagency systems for referring and handling GBV. However, in Ethiopia the situation is much different, with fewer resources for addressing GBV and less understanding among both clients and providers of the definitions of GBV. As a result, one of our biggest takeaways from field testing the competencies in Ethiopia is a need to add in more elemental competencies, such as knowledge of the definition of GBV and intimate partner violence and details about doing no harm.

As we update the framework to incorporate feedback and examples from the Philippines and Ethiopia, HRH2030 is also developing a training on gender competency for family planning providers, and a version of HRH2030’s lifecycle approach which incorporates gender competencies. Both will contribute to increasing family planning service providers’ understanding of how gender dynamics influence provision of equitable services.

*Banner image caption: The blog authors validating the framework in Ethiopia.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.