How a Small City Can Take on the Big Challenge of Conservation Financing

March 24, 2017 | 3 Minute ReadWhat does grilled chicken have to do with watershed conservation? Jana Franke-Everett and Anselmo Cabrera explain.

Negros, the fourth-largest island in the Philippines, is best known for sugar and grilled chicken. However, the charcoal that fuels restaurant owners’ income challenges the source of livelihood for rice and sugar farmers. What is the link between a tasty grilled chicken and a cup of rice? Well, the demand for charcoal puts pressure on the island’s remaining natural forest that protects the watersheds because the forests in the uplands are a common source of wood used for charcoal production. As the forest diminishes, the steady stream of water that irrigates rice fields in the lowlands slowly turns to a trickle. “Without water, we cannot produce rice. But without a healthy watershed, we cannot produce water,” said Andre Untal, Negros Occidental’s provincial environment and natural resource officer of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

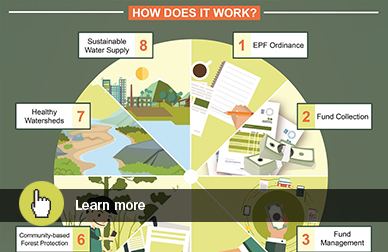

Aware of the problem, and committed to working on behalf of its more than 170,000 mainly agriculture-dependent constituents, the Bago City government passed an ordinance in January 2016 to collect an environmental protection fee (EPF) from all of the city’s water users. Its proceeds will fund forest protection work in the uplands to ensure a sustained flow of water. “With this initiative we have not only assured sustainable environmental governance financing, but also highlighted the value and importance of the ecosystem services of our forests and the role of the different stakeholders to ensure its sustainable management,” says Bago City Mayor Nicholas Yulo.

How does an environmental protection fee work?

Ecosystem services, a concept made popular by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, provide multiple benefits. Ecosystems store, purify, and regulate the water we drink or use for irrigation, provide hydro and geothermal energy resources, and strengthen resilience to adverse climate risks such as floods and droughts, among other benefits. There is consensus around the need to conserve ecosystems for them to provide these services. However, sustainably funding such protection activities remains a significant challenge especially for developing countries. One of the obstacles is assigning an economic value to the services that ecosystems provide. An environmental protection fee acts as a proxy economic value for one or more of these services. Basically, consumers of an ecosystem service, in Bago’s case, water, are charged a premium which is funneled into conservation activities that maintain the forest associated with the Bago River Watershed. A direct link is made between paying for an ecosystem service — water — and protecting the related ecosystem — the upland forest — that regulates the water’s flow. So for each gallon of water consumed in Bago City, a small fee goes into the protection of the forest. To enable fair pricing and facilitate convenient fee collection, consumers are categorized as businesses, agricultural producers, and individual households.

Ecosystem services, a concept made popular by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, provide multiple benefits. Ecosystems store, purify, and regulate the water we drink or use for irrigation, provide hydro and geothermal energy resources, and strengthen resilience to adverse climate risks such as floods and droughts, among other benefits. There is consensus around the need to conserve ecosystems for them to provide these services. However, sustainably funding such protection activities remains a significant challenge especially for developing countries. One of the obstacles is assigning an economic value to the services that ecosystems provide. An environmental protection fee acts as a proxy economic value for one or more of these services. Basically, consumers of an ecosystem service, in Bago’s case, water, are charged a premium which is funneled into conservation activities that maintain the forest associated with the Bago River Watershed. A direct link is made between paying for an ecosystem service — water — and protecting the related ecosystem — the upland forest — that regulates the water’s flow. So for each gallon of water consumed in Bago City, a small fee goes into the protection of the forest. To enable fair pricing and facilitate convenient fee collection, consumers are categorized as businesses, agricultural producers, and individual households.

Funds for protection

The money collected from water users will be reinvested into forest conservation interventions that are outlined in the city’s Forest Conservation Area Plan. This plan provides an analysis of the current state of the forest, describes desired future forest conditions, defines measurable conservation targets, and spells out the conservation strategies that will be implemented to achieve the targets. Bago’s conservation area plan focuses on two broad interventions to address forest loss and degradation: technical interventions for forest protection and socioeconomic interventions to address the causes of forest destruction.

Inspired by the Bago model, other cities in Negros have already shown interest in replicating the concept in their areas, planting the seed for a potential island-wide conservation financing model with the capacity to protect some 45,000 hectares of natural forest.

The Bago City conservation financing model is still in an early stage of implementation. However, the city government and all involved stakeholders are eager to move forward. And with plans to establish more efficient “green charcoal” production in the future, the next grilled chicken in Negros might even contribute to forest protection.

The Bago City government receives technical support through the Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program, developed and implemented by Chemonics on behalf of USAID and the Philippines’ Department for Environment and Natural Resources.