Fail Fast, Succeed Sooner: Why Investing in Innovation Is Worth the Risk

August 18, 2016 | 3 Minute ReadInnovation is flourishing in Asia. According to Stacy Edgar, investing in new ideas across the region (even if many may fail) is key to having a greater long-term impact.

It has become increasingly trendy in international development to look to Silicon Valley and the tech world’s start-up culture for inspiration in making our programs more “innovative.” Inspired by the pace at which the tech world can turn an idea into products and staples of everyday life, we aspiring innovators of international development look to their example in turning ideas into social change.

Posing the question what does innovation look like in international development, Chemonics and Arizona State University (ASU) hosted an Innovation Asia Summit in Bangkok, Thailand from June 14-15, 2016. The two days brought together 35 participants from 10 countries across Asia, including representatives from Chemonics’ field teams and our partners, donors, the private sector, universities, and government. We examined both examples of innovations in the region and the types of environments that make it possible for innovation to take root.

It has been said that innovation flourishes in flat management structures in which team members have dedicated “free time” to experiment with new ideas and rewarded for doing so. Now I’m sure there are plenty of examples to the contrary, but this doesn’t sound like most development programs that I have encountered. Nor does it describe the typical work culture that I have encountered in the 11 countries I’ve worked in across Asia. And yet, as the summit highlighted, innovation is flourishing in Asia.

In Vietnam, for example, the Ministry of Science and Technology is leading efforts to foster an “innovation ecosystem.” We were joined at the Innovation Asia Summit by Dr. Hoang Minh, president, National Institute of Science and Technology Policy and Strategy Studies, Vietnam Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST); Dr. Hoi Nguyen, director, FABLAB Network Vietnam; and Do Van Dung, PhD, president, Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology and Education (HCMUTE). Vietnam is supporting the creation of 2,000 start-up projects over the next 10 years and looking for ways to improve the regulatory environment to make it easier for entrepreneurs to start businesses. With the support of ASU, the Fablab Network in Danang has engaged more than 3,000 students and offers a space for creativity and experimentation, setting the behaviors in place among youth for “innovation culture” to continue to grow in the years to come.

Similarly, summit attendees highlighted examples of high-level initiatives to promote innovation and entrepreneurship in Singapore, Thailand, and India. Thailand’s Thammasat University’s School of Global Studies offers a degree in social enterprise and is challenging students to ask themselves as they approach their studies, “What kind of impact do you want to make?”

So what does this all mean for international development programming? At a minimum, it makes the proliferation of innovation funds, grand challenge competitions, and co-creation processes even more important. There have always been a lot of great ideas in the countries we support — sometimes hiding in plain sight, other times coming from unexpected sources. The pockets of “start-up” culture emerging across Asia mean that there are an increasing number of ideas that have some proof of concept. Through innovations funds, grand challenges, and grants, opportunity exists to further explore these ideas or help these ideas reach scale.

To do so, projects are increasingly setting aside funds to explore “high-risk, potential high-reward” ideas and see what works. Borrowing from the “Lean Start Up Methodology,” these are akin to “minimum viable product” (or to put it in project management parlance, a “minimum viable intervention”). The underlying principle is that before we invest millions in a program concept, let’s design a low-cost experiment to test our assumptions, measure, learn, adapt, and iterate, and see if our ideas achieve the impact we actually think they will. “Fail fast, succeed sooner,” as the saying goes.

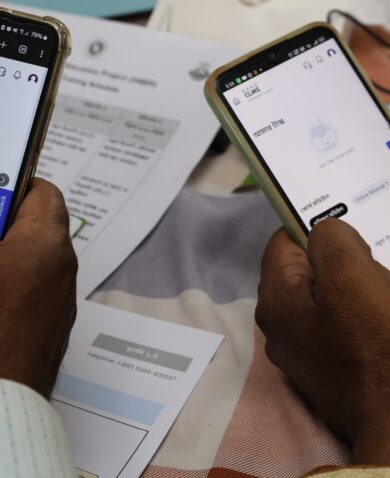

The reality of truly embracing innovation is that you’re more likely to fail more often than succeed — an uncomfortable feeling for most program managers. So why pursue innovation at all? Because when you succeed, you succeed big. In searching for a way to help banks increase their outreach to rural areas while reducing costs, your project might help invent mobile money. Or, in helping farmers to use improved agricultural technologies, you might trigger a Green Revolution.

While for many of us, the ambitions for our programs are more tempered, our ultimate goal remains the same: to improve as many lives as possible. Innovation is a pathway to get there.