Best Practices for Centering Indigenous Peoples in Development Projects

September 6, 2023 | 7 Minute ReadEngaging Indigenous Peoples is essential to driving forward locally led development, ensuring international development projects respond to and align with Indigenous Peoples’ self-determined goals and needs, and deepening projects’ impact and sustainability.

Engaging Indigenous Peoples is essential to driving forward locally led development, ensuring international development projects respond to and align with Indigenous Peoples’ self-determined goals and needs, and deepening projects’ impact and sustainability. This engagement is encoded in USAID’s Policy on Promoting the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (PRO-IP), but the question remains: How can Indigenous Peoples’ engagement in international development be equitable, inclusive, and in-depth? Four experts shared their insights and advice with us on how to engage Indigenous Peoples in the development and implementation of projects.

Our Experts

Rudy Aragon is a natural resources management specialist with over 25 years of experience, including work in the Philippines with USAID, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, local governments, and civil society organizations focused on forests, water and watersheds, agroforestry and livelihoods, Indigenous Peoples, climate, biodiversity, and environmental governance. Rudy was the Field Manager for the Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) project, managing the project’s work on the island of Mindanao.

Bani Amin is a Market System practitioner with over 30 years of experience in development and private sector engagement. He has managed strategic and complex donor-funded projects to drive inclusive economic growth in rural Bangladesh. His areas of expertise include project management, market system change, value chain development, monitoring and evaluation, financial and economic analysis, strategic planning, and writing technical papers. He is currently the deputy chief of party on the Feed the Future Bangladesh Horticulture Activity implemented by Chemonics.

S M Faridul Haque is a development practitioner, currently working with Chemonics as a gender and social inclusion specialist. He has contributed to promoting women’s empowerment and gender integration in different aspects of the development sector including the agriculture value chain, integrated water resources management, private sector engagement, food security, and the circular economy.

José Ignacio Giraldo Arango has more than two decades of experience in community processes that promote nature conservation and protection of indigenous knowledge systems. He has worked closely with Indigenous communities in emblematic places such as the Amazon basin, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and the Serranía del Perijá. His role as Indigenous Peoples specialist at Chemonics in Colombia since 2017 has been vital to the participation of traditional authorities and indigenous communities in the conservation, management, and sustainable use of biodiversity in a part of the Amazon territory.

Best Practice 1: Understand the roots of cultural practices, local Indigenous governance, community relationships, and beliefs

Rudy Aragon said, “The relationship begins during project preparation; it should not begin during project implementation.” Prior to engaging Indigenous Peoples in development projects, it is essential to understand traditional knowledge systems and practices Indigenous Peoples maintain. Specifically, development practitioners should understand 1) rituals and practices surrounding meeting outsiders, 2) the forms of conservation, management, use, and traditional relationship beliefs about land and territory, 3) Indigenous governance systems and leadership, and 4) what development projects are already being implemented within Indigenous communities, and what are the overarching themes and goals.

Development practitioners must also understand the national, regional, and local government structures and how they interact with Indigenous Peoples. This includes learning the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and government, legal requirements for engaging Indigenous Peoples, and the history between Indigenous Peoples and the government.

This approach proved essential for the Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) project in the Philippines, which worked with Indigenous groups for conservation efforts. Rudy Aragon remembers that the Philippine government required a document affirming free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) to be signed by the Indigenous Peoples affected by the potential project, which was challenging as the Indigenous Peoples in the area had already been dissatisfied with previous development projects and felt betrayed and marginalized by those efforts. Due to this context and then changes in B+WISER’s budget, it was extremely difficult to build and maintain trust between the project and the Indigenous community. Although the issue was resolved through a peace ritual and direct and transparent communication through trusted intermediaries, Rudy emphasizes that it is of utmost importance to understand the history of development projects in the area affecting the Indigenous group and to be radically transparent, which leads into the best practice below.

Best Practice 2: Develop trust through two-sided communication

Communication is key in all development projects and with all communities and partners, as highlighted in the above example with B+WISER. Development practitioners must study Indigenous Peoples’ practices around communication, including finding out who in the Indigenous community is appropriate to approach. Then, once communication has begun, development practitioners must, in Rudy’s words, “be very, very honest and open” with Indigenous Peoples about the project itself, “particularly if it is in the proposal stage and thus is not certain.”

Other best practices for communicating with Indigenous Peoples include ensuring there are informal communication lines to supplement formal consultations, to ensure that expectations are formally outlined while also allowing for questions and communication which may not be comfortable/accessible in a formal environment. This is paramount in ensuring that FPIC for project activities is granted. Secondly, USAID’s PRO-IP highlights the importance of establishing rules of engagement and communications expectations. Thirdly, development practitioners should confirm what language communication should be in, asking Indigenous communities their preferences and ensuring communication is accessible and understandable (or if there is a preferred interpreter the project can hire). Overall, it is essential to engage Indigenous communities in an honest, direct way so that they do not feel deceived, and feel empowered to advocate for their own goals and needs.

Best Practice 3: Support the goals of the local community

Not having a one-sided decision also means not arriving with a preconceived plan but listening to communities and developing the project with them. Project plans should integrate Indigenous perspectives and goals, provide positive impacts, and ensure they do no harm to Indigenous people. This contributes toward project sustainability and impact if it enables Indigenous Peoples to ensure that their culture, spiritual beliefs, and livelihoods are maintained and strengthened. José Ignacio Giraldo Arango saw this frequently in his work with Indigenous Peoples and conservation projects in Colombia, such as USAID Natural Wealth. He emphasized that recognizing Indigenous spiritual practices and traditional knowledge systems is nearly always in line with mitigating climate change and preserving natural resources because of shared goals to protect, conserve, and bolster local ecosystems and biodiversity. Indeed, although Indigenous Peoples make up only 5% of the world’s population, they protect 80% of the world’s biodiversity.

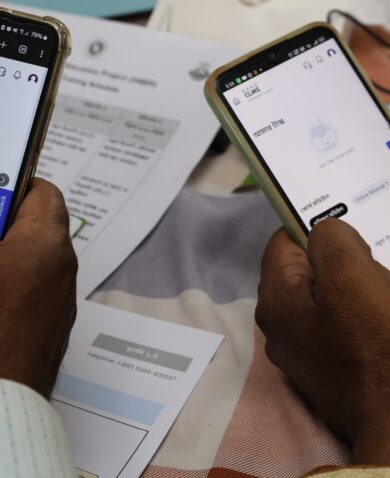

In economic growth and development projects, it is important to conduct an initial assessment to determine what markets are most relevant to Indigenous communities, and thus address their livelihoods and goals through interventions to empower Indigenous Peoples in that market. For example, in Bangladesh, Bani Amin and Faridul Haque focused on the coffee industry and supporting coffee farmers because a vast majority of these individuals were Indigenous. Due to this targeted support, Indigenous farmers’ income increased by more than 2.5 times, with a majority of Indigenous farmers using their income to expand their existing gardens, support their families’ education, and/or on improved housing.

Best Practice 4: Train staff to engage Indigenous Peoples

Lastly, it is of utmost importance for projects to successfully train their own staff to maintain communication and transparency with Indigenous Peoples. This is closely related to Best Practice 1, because of the time and expertise it requires to understand Indigenous cultural practices, governance, community relationships, and beliefs before engaging Indigenous Peoples. Furthermore, this is essential for effective communication because if the project does not have enough or appropriately-trained staff to ensure continuity in communication, relationships may sever and trust could falter, which not only sets the project back but fail to address Indigenous goals and requests.

It is also useful to leverage trusted relationships that ensure alignment with local priorities. When navigating the coffee market in Bangladesh, Bani and Farid’s project the USAID Feed the Future Bangladesh Horticulture, Fruits, and Non-food Crops Activity, “got easier when we identified the processors who were involved in the business with local people for previous years; as a result, they had a kind of trust already… so it was very easy for us to get the Indigenous Peoples connected with the activities.” As Rudy mentioned, it is important to work with trusted local partners (including individuals and/or NGOs) who have long-standing relationships and can mediate between development practitioners and Indigenous Peoples.

Overall, the most important skills in staff who will be engaging Indigenous Peoples are effective listening and honesty. As per USAID’s PRO-IP, “Consultations should be able to serve as pivot points to influence and redirect program design if it no longer aligns with the priorities of Indigenous Peoples.” Staff engaging Indigenous Peoples must not only be knowledgeable but also open to learning more.

Best Practices in Action

Indigenous Peoples have been historically marginalized and excluded from the economic, social, and political spheres. USAID recognizes this and has published the PRO-IP to integrate Indigenous Peoples’ self-determined goals in development projects to create positive change. Development practitioners must prioritize and center Indigenous Peoples as stakeholders in development projects and can utilize the above best practices to do so.

Banner image caption: Indigenous coffee processors in Bandarban, Bangladesh are strengthening the coffee supply chain. Photo supplied by the USAID Feed the Future Bangladesh Horticulture, Fruits, and Non-food Crops Activity.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.