Ecological Fiscal Transfers: Tying Ecological Indicators to Fiscal Policies

July 15, 2022 | 5 Minute ReadEcological fiscal transfers compensate sub-national governments for their investments in nature.

Governments around the world, from the national to the village level, have been devising, implementing, and regulating innovative tools, like payment for ecosystem services and sustainable production certifications, to combat and adapt to environmental problems like climate change and deforestation. However, despite these innovative tools, sub-national governments face a daunting challenge: They are often responsible for achieving national environmental goals, but rarely receive adequate funding for their efforts. Nature conservation typically represents a cost and, in many instances, means foregoing more profitable uses of natural resources for economic activities that generate revenues in the short-term. In addition to this trade-off, local governments could be further dissuaded by the potential “free-riding” off their conservation efforts, where neighboring jurisdictions – and even other countries – benefit from the services provided by nature without having to pay for them. For example, a healthy forest upstream can improve water quality for communities downstream.

Indonesia is one such country where economic development has been prioritized by sub-national governments over nature conservation. With the country’s democratization and decentralization processes over the last couple of decades, local governments gained greater autonomy, enabling them to make contextually appropriate decisions, but also driving them to become more revenue-oriented to meet their financial needs. With decentralization, the central government allowed sub-national governments to retain a greater share of produced fiscal revenues to meet their needs. For example, the Indonesian government redistributed timber royalties, increasing the sub-national share to 80 percent. As a result, sub-national governments justified the exploitation of forests and other natural resources to generate revenues and drive economic development at the expense of local, national, and global conservation interests.

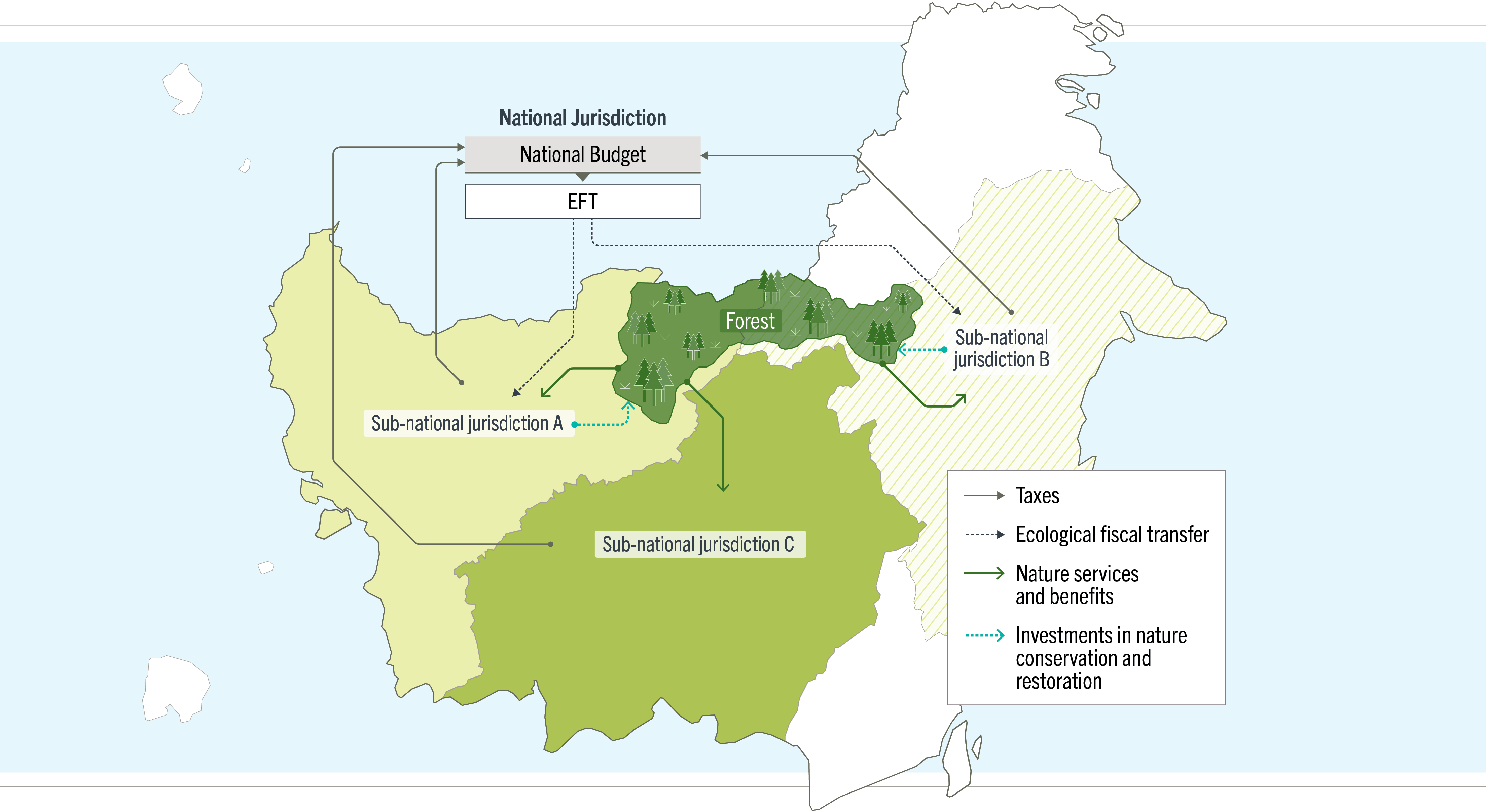

A partial solution to the difficult compromise between nature conservation and economic development for local governments is the use of ecological fiscal transfers (EFTs). EFTs are a type of intergovernmental fiscal transfer (IGFT), but with a conservation or ecological purpose. While the goal of a traditional IGFT is to compensate sub-national jurisdictions for public infrastructure and service provision, EFTs compensate for biodiversity and ecosystem service provision. Although IGFTs have been active in Indonesia since the early 2000s, EFTs are a more recent development with different levels of transfer – national to provinces, districts, or villages – currently being piloted. As presented at this year’s XV World Forestry Congress in Seoul, the Build Indonesia to Take Care of Nature for Sustainability (BIJAK) project – a USAID-funded activity implemented by Chemonics to improve land use governance, reduce wildlife trafficking, and strengthen conservation area management – drove this innovative mechanism onto the national and regional political agenda between 2016 and 2021 through an EFT assessment and improvement process.

Underlying logic of ecological fiscal transfers by Loft, Gebara, and Wong (2016), licensed under CC BY 4.0 International. Adapted from original by Chemonics International.

Opportunities and Challenges of Using EFTs for Conservation

Based on BIJAK’s experience testing the potential use of EFTs to incentivize nature conservation, as well as other examples from Indonesia, we have identified some key opportunities and challenges to consider for implementation and replication of this mechanism in different contexts.

The benefits of EFTs include:

- Promote Nature Conservation and Restoration. The main purpose of EFTs is to compensate sub-national governments for the cost and effort invested in nature conservation and restoration, although the specific uses and types of conservation projects, and associated indicators, vary in response to local needs and capacity. For example, EFTs have been set up based on the size of protected areas (Brazil), forest cover (India), and other environmental indicators like air and water quality, waste management, and reduction in forest fires (Indonesia). Although results have been mixed, positive outcomes include increased protected and forested areas, and a significant drop in pollution.

- Promote Fiscal Redistribution and Equalization. One of the core features of EFTs is that they do not imply additional funds – governments already struggle with tax revenue collection – but rather the redistribution of available revenue based on ecological indicators. Traditional IGFTs distribute revenue based on social and economic indicators such as gross domestic product and population, but do not consider environmental indicators. As expected, local jurisdictions with vast natural resources have greater fiscal needs to preserve nature, but usually have less fiscal capacity since those natural resources do not generate as much revenue as other activities like agriculture or mining. With EFTs, fiscal resources are distributed among sub-national governments based on pre-determined environmental indicators like forest cover or water quality, or other conservation or environmental needs, apart from economic and social factors. Sub-national governments receiving lower transfers due to, for instance, low GDP and population size, could receive higher transfers thanks to greater forest cover.

- Decentralize Decision-Making. EFTs strengthen decentralized environmental governance. Since natural resource conservation decisions often fall on sub-national governments, they are more likely to consider local knowledge and experience in their decision-making processes. For example, BIJAK advocated for applying an EFT mechanism following forest management criteria like empowerment of forest farmer groups, operationalization of forest management units, and area of forests under local management, which created opportunities for villages to be directly involved in biodiversity conservation.

However, EFTs also present important challenges that must be carefully considered before being implemented:

- Depend on Political Will. Since EFT implementation calls for fiscal policy reform determining the allocation of funds based on ecological indicators, proponents of this approach need to generate political momentum and ensure political will. Despite encountering this challenge in Indonesia, BIJAK was able to successfully move from design to pilot implementation of EFTs in a few years. The project did this by working with the Partnership for Governance Reform, a multi-donor trust fund, to host public discussions with a broad range of stakeholders – such as civil society organizations, academia, donor-funded projects, the National Development Planning Agency, the Ministry of Villages, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Home Affairs, and different levels of government agencies – to introduce EFTs and present recommendations for different EFT schemes that may work for Indonesia. In particular, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry expressed great enthusiasm and proposed regulatory revisions to institutionalize EFTs.

- May be Bound to Unconditionality. In line with the principle of decentralization of power, traditional IGFTs tend to be unconditional payments, meaning that sub-national governments have the autonomy to decide how to use these funds based on their current priorities. The disadvantage of unconditionality is that fiscal revenues, like those generated from EFTs, may be used for public needs other than conservation. To avoid this and to ensure sustainable investments in conservation, conditionality can be included as a requirement, where revenues generated from conservation must be allocated to conservation or restoration efforts.

- Require Effective Data Collection, Monitoring, and Evaluation Systems. As mentioned before, EFTs are made based on ecological indicators, which could go beyond the government’s existing data and monitoring capacity and could require additional effort to set up. More robust indicators related to environmental quality and performance, such as observed carbon emissions, result in more effective EFTs, but simple indicators like tree cover and protected area surface also work well. In Indonesia, BIJAK is proposing water quality, air quality, forest cover, and other forest management-related indicators. It is also worth mentioning that once monitoring protocols are established, transaction costs for data collection are significantly reduced because they become standardized and part of the EFT routine data requirements.

Scaling Up the Use of EFTs

If we are to halt deforestation, restore degraded lands, and sustainably use forests, all funding sources will be required –government, private, and official development assistance. EFTs have been implemented in very few countries to date, mostly in Brazil, Portugal, France, China, and India, but they are proving to have enormous potential: Currently EFTs amount to 20 times the global official development assistance for forestry and their value is expected to grow even further, although their net impact on nature and livelihoods is yet to be determined. Despite the challenges, EFTs can be used as simple mechanism to encourage nature conservation and restoration while promoting environmental governance decentralization. Furthermore, EFTs are a public sector instrument with the potential to enable the success of other forestry conservation and restoration mechanisms, namely Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+).

Banner image caption: Woman in Indonesia. The photo was taken by the Indonesia BIJAK project.

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.