Context and Adaptation: The Secret Ingredients of Supply Chain Innovation

November 3, 2023 | 4 Minute ReadIn an innovation-friendly environment, situation-specific innovations are locally developed, producing a strong sense of ownership and accountability and, by extension, a higher chance of success.

A few years ago, I attended a roundtable discussion on private sector engagement in public health supply chains. Several business leaders shared their wisdom about how to make private sector supply chain partnerships work. There was a lot of discussion about technology and other interesting subjects, but the insight that really stuck with me was when one speaker said that the key factor for success was mindset. He advised us to accept that we won’t get new approaches right the first time, or even the second or third time, and to manage expectations and approach it as a process of learning and adaptation.

That event made me reflect on how we approach innovation, a word we often hear in the public health supply chain space. Donors, lower- and middle-income country (LMIC) governments, and their partners are constantly seeking new ways to organize and manage supply chains — and for good reason.

Expected trends over the next few years in LMIC health service provision indicate that many governments will face increasing pressure to do more with less. Moving HIV services from an emergency footing to chronic care, grappling with the demands of moving towards universal health coverage (UHC), and planning for the next epidemic — all these pressing needs are going to require new or improved ways of thinking about and delivering health services in places where funds are scarce. The costs of drugs and medical supplies, and the supply chains that deliver them, are typically the second largest cost category in a health system, after human resources, so the benefits of innovating in supply chains are obvious.

Innovating Well

How can we choose the right innovations for a given situation? How will we know if they have succeeded? And how do we introduce innovations in ways that make them more likely to succeed? My experience over more than 20 years managing and advising on public health supply chains has taught me that successful innovation tends to rest on good, old fashioned quality management principles and the discipline and mindset that comes along with them. So, if you’re hoping to read a blog about supply chain innovation that talks about drones and blockchain, you’d better look away now.

Firstly, a definition. When we hear innovation, we tend to visualize something new and cutting edge. But that can mislead us. When we think about what an innovation at country level could actually look like, it is entirely situation specific. In other words, one country’s innovation, such as the introduction of a Decentralized Drug Distribution Model, could be another country’s tried and tested approach.

Why does that matter? Because it places each country’s context at the heart of the process and ensures that the way in which we apply any innovation is problem-driven and not solution-driven. It’s all too easy to learn of a new piece of technology or an entirely new approach, get excited, and look for a place to implement it. That’s not to say that learning from others’ experiences isn’t important — it’s vital. Scaling approaches from one setting to multiple settings can be a highly effective way of achieving impact quickly. But scaling is far more likely to deliver success when we understand the problems and the context of the places where we want to scale.

Innovation Friendly

It’s clear, then, that we need a framework to use at country level that helps us to prioritize the problems that need solving and to figure out where to focus our energies.

Good supply chain governance approaches, including judicious use of quality management systems, such as ISO 9001:2015, are perfectly suited to this task. They force us to continually analyze how our supply chains are doing, to review the reasons for our good or poor performance, and to agree on improvement initiatives. These initiatives can be immediate, such as removing a step in a process to save time, or longer range, such as initiating a cost-benefit analysis of logistics outsourcing. But all of them must be linked to a clearly identified problem.

What could this look like in practice? Here are some features of what I would call an “innovation-friendly” environment for LMIC public health supply chains:

- Supply chain governance structures in place, where all partners are held accountable for their contributions and responsibilities. This is not easy to achieve but is an important foundation for all supply chain improvements.

- Regular data-driven supply chain performance assessments, led by government and supported by partners as necessary to understand performance and anticipated future trends.

- Empowered “innovation” or “solution” teams, with a remit to spend time analyzing supply chain problems and developing situation-specific innovation ideas.

- A “learn by doing” mindset, whereby improvement over time is the goal rather than perfection at the first attempt.

- Government leading the process and making the crucial decisions on what to prioritize.

Situation Specific

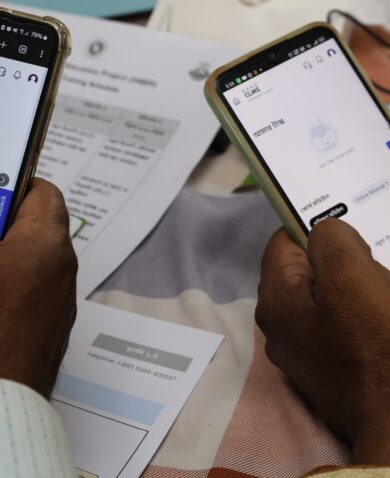

In this kind of environment, situation-specific innovations are locally developed, producing a strong sense of ownership and accountability and, by extension, a higher chance of success. Chemonics’ supply chain technical assistance (TA) in the USAID Global Health Supply Chain Program-Procurement and Supply Management (GHSC-PSM) project and the GHSC-TA Francophone Task Order strives to create exactly this kind of environment by observing the following principles:

- Intentionally providing expertise that can lead or coach, depending on the situation. Often, this means making sure that we ask the right questions and provide insights into problems without leaping straight to a solution.

- Striving to support the creation or development of supply chain governance structures. Addressing governance usually means working with a broad set of actors including several outside of the health sector.

- Maintaining a clear focus on data culture. This often involves finding ways to improve the incentives for good data practices.

- Consciously integrating the principles of Thinking and Working Politically into our standard ways of working.

Several examples speak to the fruits of this approach in action: our work designing tools for inventory rebalancing and anomaly detection in the supply chain; the introduction of Activity-Based Costing and Activity-Based Management principles in Kenya, Lesotho, and Uganda; or our work optimizing distribution activity in Zambia. All of these started with a clear problem definition, deep understanding of the local context, and a willingness to adapt and improve towards a goal.

Of course, all of this is about more than just innovation. It’s about creating the right environment through management discipline, continuous improvement, and the long-term mindset required for sustained success.

We want to hear from you! What are your experiences of innovation in public health supply chains? What have you learned about successful approaches?

Posts on the blog represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Chemonics.