Know Your SDGs: The Reality of Education for All

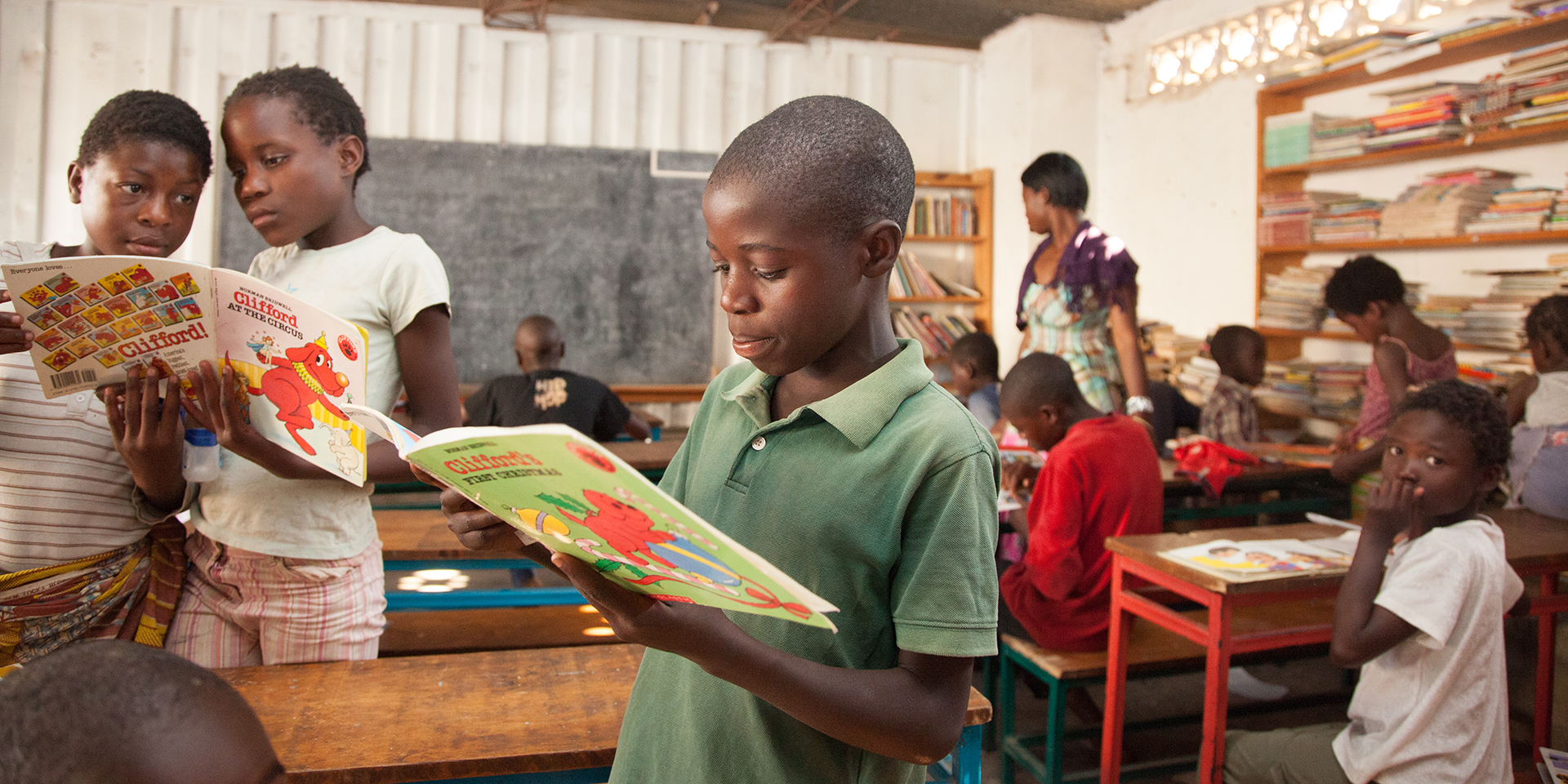

July 30, 2015 | 4 Minute ReadProposed Sustainable Development Goal 4 aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

With the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) set to expire at the end of this year, the United Nations General Assembly will be meeting in September to discuss the next phase of the MDGs. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a compilation of 17 goals and 169 targets, are set to replace the MDGs. This presents an opportunity for the international community and brings us to a critical juncture in the development world: Will the SDGs be too much too soon, or too little too late? This question is ever-present in looking toward the future of education under the SDGs and defining the focus of the international community.

Education in the SDGs

While education is woven throughout the SDGs, specifically in proposed Goals 3, 4, 8, and 13, this analysis focuses primarily on Goal 4: “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.” There are 10 sub-indicators ranging from ensuring girls and boys complete primary and secondary education to increasing the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills for employment. The goal itself seeks to create education that takes into account marginalized groups, including those with disabilities, and seeks to address gender and economic disparities. The goal focuses on life skills such as critical thinking, basic math, and civic participation.

With the wide range of issues covered under Goal 4, there is some debate as to what the goal will look like in practice. According to Joshua Muskin, a senior fellow at the Center for Universal Education, the new SDG goal does not offer a practical application for how to achieve quality education. Others believe that the goal is too unwieldy and all-encompassing to be achievable. Liesbet Steer, also a fellow at the Center for Universal Education, stressed the importance of having realistic goals and the resources available to accomplish the goals. She also offered recommendations for how the SDG education goal could actually be achieved in spite of its seemingly unreachable indicators. With the varying opinions, the verdict is still out on what the SDGs will yield.

Comparing the old with the new

Setting targets and goals is nothing new in international development. However, measuring these targets and evaluating the cost of the investment and what works best in the context of education is new. To begin deconstructing this, the best way to understand the context of the SDGs is to examine what was accomplished under the MDGs.

In 1990, UNESCO and other international organizations launched the ‘Education for All’ campaign with the goal of universal primary education by 2000. By 1999, net enrollment in Africa was only 57 percent. So the target was reaffirmed and the date shifted to 2015. Even though considerable progress has been made in expanding access to education, there is still much to be done. Of the 57 million out-of-school children, 33 million are in sub-Saharan Africa, with more than half being girls. There are still wide disparities between poor and rich children in completing primary school as well, and nearly 100 million children are not completing primary school. Literacy has improved, but slowly, and there are still more than 100 million young people aged 15 to 24 who lack basic literacy skills.

Though the MDGs will not be fully accomplished by the end of 2015, there has nonetheless been some progress. The recently released Millennium Development Goals Report details the following education successes from the MDGs:

- Enrollment in primary education in developing regions reached 91 percent in 2015, up from 83 percent in 2000, which means more kids than ever are attending primary school.

- The number of out-of-school children of primary-school age worldwide has fallen by almost half to an estimated 57 million in 2015, down from 100 million in 2000.

- Sub-Saharan Africa has had the best record of improvement in primary education of any region since the MDGs were established. The region achieved a 20 percentage point increase in the net enrollment rate from 2000 to 2015, compared to a gain of 8 percentage points between 1990 and 2000.

- The literacy rate among youth aged 15 to 24 increased globally from 83 percent to 91 percent between 1990 and 2015. The literacy gap between women and men also narrowed.

While there have been successes in increasing access to education, many would argue that even if education were financed completely, there is still an issue with quality. For example, teacher absenteeism significantly affects the quality of schooling, yet the indicators do not account for this. A World Bank effort to measure the quality of education in Africa found that in Uganda, only one in five elementary school teachers meet the minimum standards of proficiency in math, language, and pedagogy. Few teachers spend time actually teaching and nearly 20 percent of teachers were absent. These numbers, while specific to Uganda, tell a story that is familiar in other developing countries.

So what’s next?

Ultimately, sustainable change requires a different way of thinking than what has been done in the past. We are hopeful that by having global goals, countries, donors, and the international community will be able to focus on the same issues and invest in similar areas. While there is much discussion on the value of aid and the value of the SDGs, the main takeaway is to learn from the MDG education goal and adjust our approach to yield more and better results. We need to invest in cost-effective measures that help to educate all, especially the poorest and most disadvantaged.